A reminder for new readers. That Was The Week includes a collection of my selected readings on critical issues in tech, startups, and venture capital. I selected the articles because they are of interest to me. The selections often include things I entirely disagree with. But they express common opinions, or they provoke me to think. The articles are snippets sized to convey why they are of interest. Click on the headline, contents link, or the ‘More’ link at the bottom of each piece to go to the original. I express my point of view in the editorial and the weekly video below.

Hat Tip to this week’s creators: @edzitron, @bysarahkrouse, @dseetharaman, @JBFlint, @packyM, @KamalVC, @VaradanMonisha, @Claudiazeisberg, @IDTechReviews, @cjgustafson222, @NathanLands, @psawers, @lightspeedvp, @jaygoldberg, @avc

Contents

Editorial: Dear Sam, A Letter from a Founder to a Founder

OpenAI vs Gemini 1.5

Editorial: Dear Sam, A Letter from a Founder to a Founder.

This week let’s break the pattern and write this as a letter to Sam Altman.

Dear Sam,

It’s been a swings and roundabouts week for you at OpenAI.

I had a week like that in the spring of 1998. I was at Internet World launching RealNames to the world. RealNames invented paid clicks on keywords. Our first partner was AltaVista, and Google was our second—calling the feature "I'm Feeling Lucky."

It was the simplest technology ever. We had a keyword, bought by a customer. An example might be Disney buying "Bambi." They would buy it in every country and language they wanted and point it to a specific URL in each place. Search engines would look at the keywords you typed in (later browsers too) and if RealNames had it as a paid keyword, they would send the user to the site, with no search results. Just a direct navigation. RealNames got paid for the customer sent.

At the launch, we used the example of the keyword “Bambi” to show how superior our keywords were compared to domain names. In those days, Bambi.com pointed to a porn site. Our launch demo showed that typing "Bambi" went to Disney, but typing "Bambi.com" did not. All was well except we altered our network settings the eve of the launch, and when we demoed the use of "Bambi" at the launch, it (you can guess) went to the porn site.

Journalists wrote about RealNames as a scam and bad actors.

Luckily, we had great partners, and within 12 hours the network issue was fixed, and all was well. But for 24 hours, I felt like the world was collapsing around me. On the one hand, we launched our company, mostly to great acclaim; on the other, we were being destroyed in the tech media.

Sam, I know how this week must have felt. Your decision to pull the ‘Sky’ voice was right. And despite the horrors of the first 24 hours, this will pass.

That said, you mismanaged this entire thing. I’m sure you acted in good faith in wanting to embrace the “Her” meme. It is a good idea. And ‘Sky’ was a good effort.

It seems clear you had spoken to Scarlett Johansson and failed to reach an agreement. I’m prepared to believe you could not react fast enough to change the voice prior to the demo.

But once it went awry, you needed to do more than wait for a legal challenge before pulling it, and you needed to say something before the actress. Not doing so means that many people, probably most, think you did the entire thing on purpose.

Clearly, you did not preconceive this. If you did, then the fact that you were happy to pull the voice, and your knowledge that the actress was not prepared to have her voice used, would have stopped you before it got as far as it did. You would be very reckless to have thought you could get away with using a voice like hers without her permission.

So, you need to either go on the record and get this behind you or ignore it and hope it goes away. I think now we have ‘ScarJo’ as a word, the latter might prove difficult.

Best Regards,

Keith (A fellow Founder)

Beyond ScarJo there are some great essays this week. Packy McCormick writes about why AI will lead to more jobs and bigger companies. In framing his case he says”

Technologies are tools.

I don’t mean that in the normal way that people mean it to say that technology is neither good nor bad.

Tools are good.

Humans can build better things with tools than they can without them.

But tools aren’t the point. They’re tools.

Tools lead to new possibilities and those lead to new endeavors. Read his essay below.

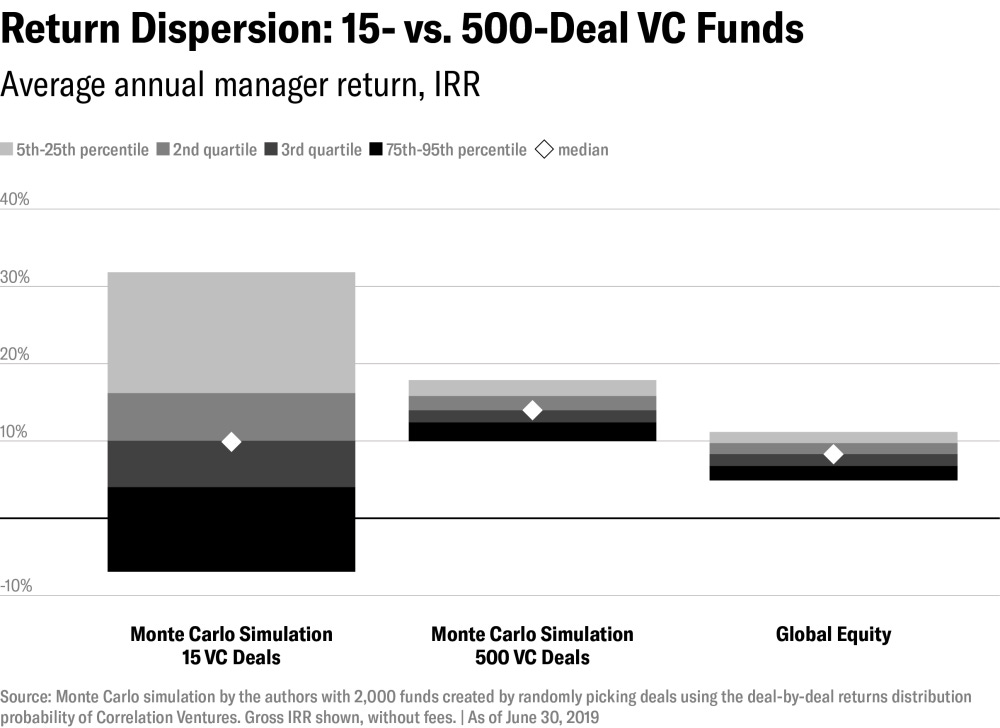

And a team made up of @KamalVC, @VaradanMonisha, @Claudiazeisberg have penned an essay called ‘The Pervasive, Head-Scratching, Risk-Exploding Problem With Venture Capital’. The main thesis is about investing in private companies versus public companies. They have a great graphic showing that the range of outcomes in Venture Capital is very wide compared to other asset classes:

Venture Capital’s top percentiles out-perform other asset classes, but most do not. The safest asset class is global equity (public company stock).

Building on this they show that large Venture investors that invest across 500 or more companies can compete with less risky assets by diversification.

This depicts a simulation of a manager doing 15 deals, compared to 500 and shows more deals equals less risk.

I recommend reading the full piece, linked in the contents above and the headline below. I think they are right, but there is a better way of derisking. The advice they give below is better than traditional venture capital, but that is a low bar:

To de-risk venture capital, CIOs simply need to acknowledge that VC math is different from public markets math. The importance of low-probability, excess-return-generating investments means that proper diversification requires a portfolio of at least 500 startups.

It will take work to assemble such a portfolio. It is hard to do by investing directly. Current funds and funds-of-funds are rarely designed with diversification in mind. Instead, they concentrate funding in a small subset of ultra-popular entrepreneurs, sectors, and geographies, which risks driving down returns on capital, leaving higher-return strategies underfunded.

Investors who allocate and diversify their funds wisely and accept the evidence will not only achieve better and less-volatile returns, but will also ultimately nudge GPs to finally design diversified funds.

In my day job - also about de-risking venture - we use AI to reduce risk, removing companies that are highly unlikely to be successful. The remaining companies (about 7% of the full set of venture backed companies) out-perform the market in a narrower band of outcomes:

Here is how the SignalRank Index compares to the S&P500 and the NASDAQ. We assume an investor puts $1 into the S&P, the NASDAQ and The SignalRank Index in each year from 2014-2019 and then show the returns from each (average and median in the case of SignalRank).

The median outcome from venture investments is that the investor loses money. The average is a lot better. But almost no managers achieve the average. By using AI to reduce risk we get the average outcome in 2014 to be 4.31x the investment (the white numbers), compared to the S&P500 1.39 and the NASDAQ 1.89. SignalRanks Median outcome is 2.24.

De-risking venture capital is important and the writers of the essay show that it is possible to de-risk by diversification. But we can do even better by both diversifying and using data intelligence to remove downside outliers.

I will leave you with that thought. More next week

Essays of the Week

Sam Altman Is Full Of Shit

EDWARD ZITRON, MAY 21, 20248 MIN READ

Note: In my last newsletter, I said that my next post would be the second part of my Facebook autopsy. Don’t worry, that’s still coming, but given the recent drama between Sam Altman, OpenAI, and Scarlett Johansson, I felt the need to write something. Don’t worry, I won’t be doing bonus posts every week.

Eight days ago, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, giddy from the high of launching the faster-responding model GPT-4o, tweeted the word "her." Altman was referencing the fact that OpenAI had just debuted a voice assistant inspired — or not, as the case may be — by Scarlett Johansson in the movie Her, where she voiced an AI. In an interview with The Verge, OpenAI CTO Mira Murati said that the voice assistant was not meant to sound like Johansson, and on Monday morning, the company abruptly chose to pull down the voice from ChatGPT, saying that it wasn't meant to sound like her, and that it belonged to a completely different unnamed actress. Altman, in a separate blog post, said that ChatGPT's new model "feels like AI from the movies."

Later on Monday, The Verge also reported that OpenAI had been "in conversations" with Johansson's representatives. Yet a mere half an hour later,Johansson told NPR in a statement that she'd been solicited twice — once in September, and once two days before the announcement — to bring her voice to ChatGPT, something she'd declined to do, and on hearing the demo, she chose to retain legal counsel and had forced Altman and OpenAI to pull down the voice. In a statement released to the press, Altman subsequently claimed that the actress for Sky was cast before the company reached out to Johansson.

This begs the question: If the voice behind Sky belongs to an entirely different person, and was not, as seems to be the case, inspired by or stolen from Johansson, why did OpenAI try to license Johansson’s voice? There are two possibilities. First, it was a coincidence, and OpenAI is trying to cover its arse. Nitasha Tiku, a tech culture writer for the Washington Post, noted the similarity in September of last year when attending an OpenAI demo event and raised the issue to a company exec, who denied deliberately copying Johansson’s likeness. Was it all just a giant mistake? One big unhappy coincidence?

I don’t think so, not least because of the not-so-coy hints dropped by Altman around the launch of GPT-4o.

The second possible explanation — and the most plausible in my opinion — is that OpenAI simply pirated her likeness and then tried to bring her onboard in a failed attempt to eliminate any potential legal risk. Given OpenAI’s willingness to steal content from the wider web to train its AIs, for which it’s currently facing multiple lawsuits from individual authors and media conglomerates alike, it’s hardly a giant leap to assume that they'd steal a person’s voice.

As an aside: It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that Johansson didn’t jump at the chance to work with OpenAI. As a member of the SAG-AFTRA actor’s guild, Johansson was a participant in the 2023 strike that effectively deadlocked all TV and film production for much of that year. A major concern of the guild was the potential use of AI to effectively create a facsimile of an actor, using their likeness but giving them none of the proceeds. The idea that, less than one year after the strike’s conclusion, Johansson would lend her likeness to the biggest AI company in the world is, frankly, bizarre.

Just so we are abundantly, painfully, earnestly clear here, OpenAI lied to the media multiple times.

Mira Murati, OpenAI's CTO, lied to Kylie Robison of The Verge when she said that "Sky" wasn't meant to sound like Scarlett Johansson.

OpenAI lied repeatedly about the reasons and terms under which "Sky" was retired, both by stating that it "believed that AI voices should not deliberately mimic a celebrity's distinct voice" and — by omission — stating that it had been "in conversations" with representatives to bring Johansson's voice to ChatGPT, knowing full well that she had declined twice previously and that OpenAI's legal counsel were actively engaging with Johansson's.

This company has recently been asked — and failed to answer — whether it trained its video-generating AI Sora using videos from YouTube. Last week was a busy one for OpenAI, with Vox reporting that people leaving OpenAI have to sign a restrictive NDA that, when violated, they lose all vested equity shares in the company, something which Sam Altman has claimed isn't the case, which we all have to take his word for.

This was also the week where OpenAI dissolved its team focused on the long-term risks of AI, and Jan Leike, its former co-head, resigned claiming that he disagreed with the "core priorities" of OpenAI's leadership, saying that his team — which, to be clear, dealt with the safety implications of artificial intelligence —was "sailing against the wind" at OpenAI, and that it was becoming "harder and harder" to get compute for his research. Leike added that at OpenAI, "safety culture and processes have taken a backseat to shiny products." Oh, and co-founder Ilya Sutskever resigned, the very same guy who was behind Altman's brief exile from OpenAI, before repenting and returning to the fold.

I should also add that Altman has previously stated that "humanity needs to solve for AI safety."

So, let's review. In the last week, OpenAI has repeatedly lied about a voice product, dissolved its AI safety team, and had two major players in the company resign — one of whom tried to oust Sam Altman late last year, and the other who clearly despises the direction of the company. And unlike Sam Altman, both Sutskever and Leike are actual computer scientists that build things versusspecious hype men who people have been trying to fire for a decade. Seriously,staff went to the board to get him fired from his first company twice, Paul Graham personally flew into San Francisco to fire him from yCombinator, and he was so dramatically fired from OpenAI that he had to run crying to venture capitalist Reid Hoffman and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella to make him CEO again and install the Avengers of Capitalism as the new board.

I'll cut to the chase: it's time to stop listening to anything that Sam Altman has to say. Sam Altman is full of shit, and his reign at OpenAI has been defined far more by its empty promises than any realized dreams

Behind the Scenes of Scarlett Johansson’s Battle With OpenAI

Spat between star and Sam Altman’s company shows why Hollywood is worried about how artists’ work is used in the age of generative AI.

By Sarah Krouse , Deepa Seetharaman and Joe Flint

May 23, 2024 at 9:00 pm ET

Scarlett Johansson’s powerful Hollywood agent, Bryan Lourd, wanted answers when he made an urgent call to Sam Altman last week: What do you think you’re doing?

Altman’s artificial intelligence powerhouse, OpenAI, had for months unsuccessfully courted Johansson, who memorably voiced an AI assistant in the 2013 film “Her.” Last September, Johansson turned down an offer to work with OpenAI and voice a new assistant feature.

Altman didn’t give up. In mid-May, he texted Lourd, co-chairman of Creative Artists Agency, asking if Johansson might reconsider—he wanted to show the actress something he’d been working on, people familiar with the interaction said. The camps couldn’t settle on a time to meet.

Then on May 13, OpenAI showcased an updated AI system, equipped with new voice assistants for its Chat GPT tool, including a female named Sky.

Johansson was surprised and angry. She and Lourd thought—and others agreed—that Sky’s voice sounded “eerily similar” to the actress. Lourd and the actress spent the morning fielding calls and emails from friends and associates, some of whom worried that OpenAI had simply appropriated Johansson’s voice without permission.

In a 2023 product update, OpenAI published a sample of its voice assistant called "Sky." OpenAI said that the voice was added to ChatGPT and showcased online in a demonstration video on May 13.

When Lourd confronted Altman, however, the OpenAI chief executive was incredulous. Did they really think the voice sounded like Johansson? Was she mad?

So began the most dramatic episode yet in the collision between Hollywood and the exploding world of artificial intelligence.

The emergence of AI as a rapidly advancing and perhaps unstoppable force has sparked deep anxiety in creative industries that for decades have been governed by strict rules of how creators are compensated for their work. The reason is that the language models that power generative AI chat tools are typically made using text, images, music and videos hoovered up from across the internet. That can include material that is copyrighted, valuable and often paywalled—like Scarlett Johansson’s voice.

Johansson—who just three years ago waged a blistering and public legal campaign against Disney—hired a legal team to demand answers from Altman and OpenAI and issued an excoriating statement.

OpenAI, however, said Sky was never intended to resemble Johansson, and that the company had hired a voice actor who recorded the part before any outreach to Johansson. People close to Altman say he wanted Johansson to be involved in the voice project, potentially as an additional voice or to promote the product.

OpenAI paused use of the Sky voice on Sunday after receiving legal letters from Johansson’s team of representatives. Altman said Monday evening in a statement that he apologized for failing to communicate better.

OpenAI has spent months making the rounds with studios and producers showcasing its Sora text-to-video tool and discussing potential licensing deals, according to people familiar with the meetings. News Corp, owner of The Wall Street Journal, struck a content-licensing partnership with OpenAI Wednesday that could be worth more than $250 million over five years.

A cash-strapped Hollywood has tiptoed toward generative AI tools, hoping it will save money on tasks involving scripts, production schedules and visual effects. Boosters say AI will speed up mundane tasks, offer payouts to actors who grant rights to AI versions of their voices and could help stars create synthetic doubles of themselves to maximize the number of commercial projects they can pursue at once. Some stars have begun hiring advisers to help them spot instances of their likeness being misused and issue takedown notices.

Yet as talent contemplates what AI means for the future use of their likeness, studios continue to explore opportunities to license content to data-hungry AI companies or build engines that they can use internally.

Media companies are starting to do their own deal making. Disney is discussing a deal with Microsoft—OpenAI’s strategic partner and biggest investor—for a private generative AI tool that could be trained on Disney’s library of content and other data and used internally, according to people familiar with the matter. The company has also had recent discussions with OpenAI and others. Disney declined to comment. Microsoft declined to comment.

Lawmakers are just starting to take notice of the changing landscape for intellectual property rights. There are bills in Congress that aim to protect artists including the “No Fakes Act” which would prohibit the unauthorized use of digital replicas without consent. Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed into law the Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Securities (ELVIS) Act in March, which makes people’s voices protected personal rights.

Deep fears remain that the very tools that could transform the industry might be able to do so only because they were built using decades of creative work published on the internet without permission or compensation. For many, the Johansson incident was proof positive of how the “move fast and break things” ethos of developing new technologies could erode the cornerstone of Hollywood artistry.

“How these companies align with the actual individuals and creators is what’s key here—the verification of authenticity and receiving consent, and remuneration for consent,” CAA’s Lourd said in a statement. “It’s not too late for these companies to slow down and put processes in place to ensure that the products that are being built are built transparently, ethically, and responsibly.”

Sky voice actor says nobody ever compared her to ScarJo before OpenAI drama

OpenAI’s feud with Scarlett Johansson could cost Hollywood AI deals.

ASHLEY BELANGER - 5/23/2024, 11:27 AM

Sean Zanni / Contributor | Patrick McMullan

OpenAI is sticking to its story that it never intended to copy Scarlett Johansson's voice when seeking an actor for ChatGPT's "Sky" voice mode.

The company provided The Washington Post with documents and recordings clearly meant to support OpenAI CEO Sam Altman's defense against Johansson's claims that Sky was made to sound "eerily similar" to her critically acclaimed voice acting performance in the sci-fi film Her.

Johansson has alleged that OpenAI hired a soundalike to steal her likeness and confirmed that she declined to provide the Sky voice. Experts have said that Johansson has a strong case should she decide to sue OpenAI for violating her right to publicity, which gives the actress exclusive rights to the commercial use of her likeness.

In OpenAI's defense, The Post reported that the company's voice casting call flier did not seek a "clone of actress Scarlett Johansson," and initial voice test recordings of the unnamed actress hired to voice Sky showed that her "natural voice sounds identical to the AI-generated Sky voice." Because of this, OpenAI has argued that "Sky’s voice is not an imitation of Scarlett Johansson."

What's more, an agent for the unnamed Sky actress who was cast—both granted anonymity to protect her client's safety—confirmed to The Post that her client said she was never directed to imitate either Johansson or her character in Her. She simply used her own voice and got the gig.

The agent also provided a statement from her client that claimed that she had never been compared to Johansson before the backlash started.

This all “feels personal," the voice actress said, "being that it’s just my natural voice and I’ve never been compared to her by the people who do know me closely.”

However, OpenAI apparently reached out to Johansson after casting the Sky voice actress. During outreach last September and again this month, OpenAI seemed to want to substitute the Sky voice actress's voice with Johansson's voice—which is ironically what happened when Johansson got cast to replace the original actress hired to voice her character in Her.

Altman has clarified that timeline in a statement provided to Ars that emphasized that the company "never intended" Sky to sound like Johansson. Instead, OpenAI tried to snag Johansson to voice the part after realizing—seemingly just as Her director Spike Jonze did—that the voice could potentially resonate with more people if Johansson did it.

"We are sorry to Ms. Johansson that we didn’t communicate better," Altman's statement said.

Better Tools, Bigger Companies

Atoms, Bits, and $100B Techno-Industrials

MAY 22, 2024

Not Boring by Packy McCormick

Tech is going to get much bigger. I don’t want to brag, but I’ve been yelling thisthrough the depths of the bear market and I’ll yell it through the next one. I may be dumb, but I’m consistent. And it looks like, for now at least, I’m right.

On Monday, the Nasdaq hit an all-time high and crypto soared on news that an Ethereum ETF is likely to be approved. Yesterday, a bunch of startups announced huge raises.

What’s happening? Wasn’t tech falling apart just a few months ago? Aren’t rates still high?

Zoom out. This is just the beginning. Progress is accelerating, and what’s been most striking to me is how evenly distributed progress has been across sectors.

Yesterday’s funding announcements included AI, of course (Scale raised $1 billion, Suno raised $125 million, and French company H raised a $220 million seed), but also included crypto (Farcaster raised $150 million), identity (Footprint raised $13 million), biotech (Monte Rosa Therapeutics raised $100 million), and defense (Anduril is rumored to be raising $1.5 billion, drone company Neros raised $10.9 million the day before). To top it all off, I turned on Invest Like the Best and listened to a great conversation with Skyryse CEO Mark Groden about making personal aviation safe and accessible. We might actually get our flying cars!

The rumors of venture capital’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. The most successful tech companies built today will be bigger than any that have come before, for the simple reason that they have better tools to build with. My bet is that those tools have gotten good enough that they can mount serious attacks on the biggest sectors of the economy and reshape the physical world.

That’s bold. Let me explain my philosophy.

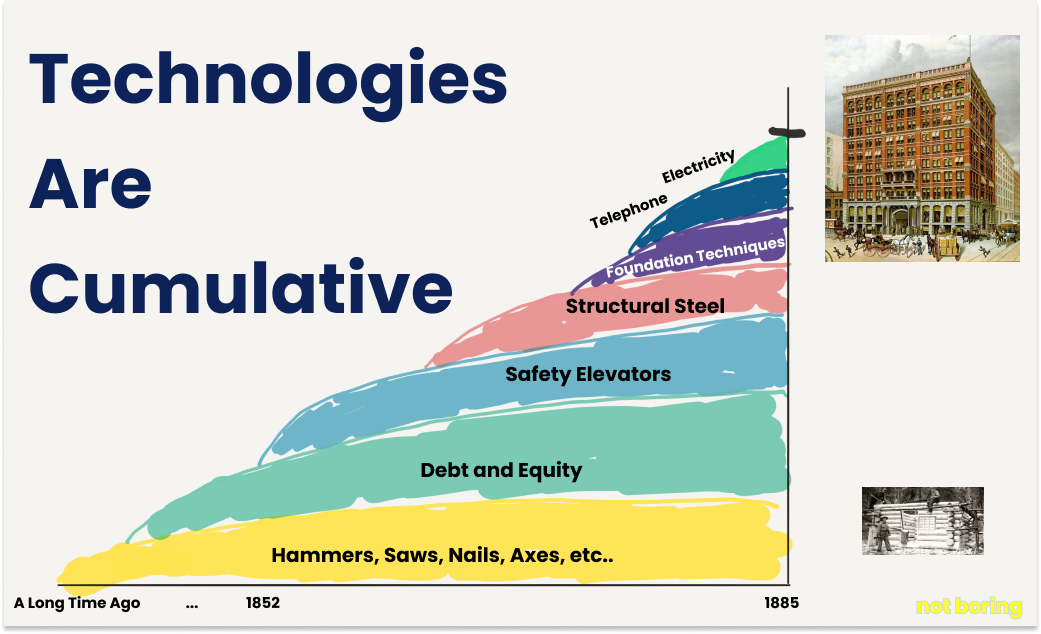

Technologies are Tools

Technologies are tools.

I don’t mean that in the normal way that people mean it to say that technology is neither good nor bad.

Tools are good.

Humans can build better things with tools than they can without them.

But tools aren’t the point. They’re tools.

A hammer is useful insofar as it lets people build houses. Houses are the point, along with everything else that we use tools to build to improve our lives.

Back in the day, a single person could and often did build a house with just a hammer, ax, and saw.

But think of what it took to build the earliest skyscrapers, limited as they were to just ten to twelve stories.

Building a skyscraper took all of the tools required to build a house, and many more besides: structural steel, safety elevators, fire-proofing, raft foundations, electricity, lightbulbs, plumbing, telephones, and ventilation systems. Each of those had its own history of technological development, and all came together to make skyscrapers possible.

But those were just the physical things. Building skyscrapers required investment contracts, bank loans and bonds, lease agreements, insurance, and reinsurance. Each of these, too, was developed separately over time, and all came together to make skyscrapers possible.

You could write a book on every technology that made skyscrapers possible, and fill a library with books on every technology that made those technologies possible. Think of all it takes to make one pencil.

But I think you get the point: technologies are cumulative.

The skyscraper is just one example of a much broader pattern. Across every domain, from transportation to finance to energy to healthcare, new tools make better solutions possible.

The Pervasive, Head-Scratching, Risk-Exploding Problem With Venture Capital

Three VC experts run the numbers and conclude: Everyone’s doing it wrong.

September 29, 2020

By Kamal Hassan, Monisha Varadan, Claudia Zeisberger

Venture capital demands from investors a significant risk appetite — or at least that is the perception.

Academic research into VC funds since the 1980s has shown evidence to support the notion: On average, seven out of ten portfolio companies will not return even the money invested in those startups; the majority will need to be written off. This requires heavy lifting from the remaining three (out of our imaginary portfolio of ten). Two are expected to return enough to cover all the losses; the third to provide the 20 to 30 percent internal rate of return (IRR) investors anticipate.

Venture capital, as currently commonly practiced, is rightly perceived as a risky asset class. As the below chart shows, venture fund industry returns show a very wide dispersion, with the bottom quartile of all funds losing money. This dispersion is significantly higher than in private equity funds and remarkable when contrasted with public equity, where even the bottom-quartile funds deliver 5 percent or better on average. Given the unpredictability of venture capital, one wonders indeed why VC portfolio allocations continue to grow among institutional investors, especially family offices.

Individual VC deals are indeed risky. It is also a fact that a few outlier mega-winners have an outsize impact on total industry returns. Much ink has been spilled on the selection of fund managers (the general partners, or GPs). Investors able to predict which fund managers will consistently pick those winners, if such is possible, will show exceptional returns.

But none of the above points prove that the asset class itself is risky. True asset class risk is the risk that remains after constructing a portfolio that reduces investment risk by diversifying away company- and sector-specific risk. VC fund returns appear risky because individual VC fund managers (the GPs) do not diversify away the risk in their fund portfolios. Look at the vast dispersion between top- and bottom-quartile VC funds, with bottom-quartile funds giving negative returns. This dispersion is a classic sign of a non-diversified portfolio.

How big is diversified enough? Classical portfolio theory says that in public equities, reasonable diversification effects can be expected when one combines 20 to 30 stocks, while more detailed recent studies set this number at 40 to 70. Most VC funds are of similar size: Why would this not be a sufficient number?

Two-thirds of venture deals fail, researchers have found. With such a high mortality rate, a VC fund’s actual ending portfolio size is merely one-third of its invested companies’. So to arrive at an exposure with 20 to 70 companies, a fund needs a starting portfolio of 60 to 210 startup investments. Very few funds meet this size.

In addition, experts in venture capital know that it is not a business of averages, but instead of many strikeouts and very few home runs. Significant portions of the average come from very few outlier deals. Evidence abounds. The distribution of returns in this study from Correlation Ventures shows that 0.4 percent of deals return 50 times the invested capital or more. Analysis shows that this handful of successful deals is responsible for around one-fifth of the total cash returned by the industry. To reliably access the excess returns generated by one in 250 deals, a fund size of more than 500 investments is needed. Anything less risks having a portfolio without any mega-winners.

To verify, we ran a Monte Carlo simulation of returns in two VC funds: one with 15 investments picked randomly from a set of standard expected returns, and one with 500 investments (see the chart below). For each deal, we randomly selected outcomes based on the real observed probability distribution of venture deals. The simulated VC portfolio of 15 investments behaved very similarly to the real-life VC fund returns depicted in the first chart. There is a large dispersion between the top- and bottom-quartile funds, with a median return of around 10 percent. Bottom-quartile funds lost money, and the top quartile has its own large internal dispersion.

The second bar in the chart below shows the impact on returns when the VC portfolio expands to the recommended portfolio size of 500 investments. The outcome: The dispersion for the VC portfolio returns tightens to a range of 10 to 17 percent. This range of returns from bottom to top quartile is similar in size to that of public equity funds. With suitably high diversification, VC indeed becomes an investment-grade asset.

Video of the Week

AI of the Week

Does AI have a gross margin problem?

Can AI overcome the gross margin doubters?

CJ GUSTAFSON, MAY 21, 2024

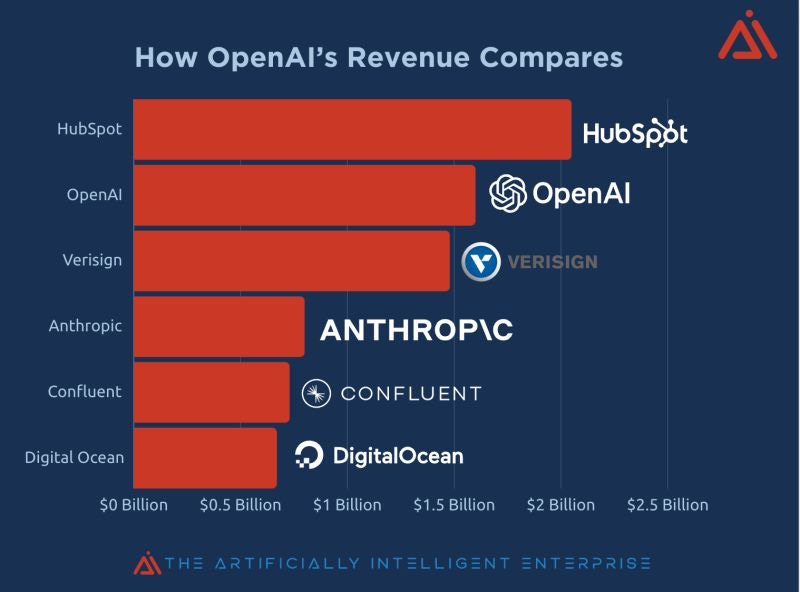

There’s no question about AI’s revenue potential. The traction is quite literally like nothing we’ve seen before.

OpenAI surpassed $1.6 billion in ARR to close out 2023, and is probably far past $2B as I write this. Anthropic is also on a roll - forecasting to hit $850M in ARR by the close of 2024.

But if we turn our eyes away from the sun for a quick moment and peruse the rest of the P&L, you’ll find that these models aren’t cheap to run.

It begs the question: What’s the longer term profitability going to look like for AI companies? Will they be fighting gross margin headwinds in perpetuity? Will anything ever “drop to the bottom”?

What’s up there, anyways?

What’s in an AI company’s gross margin? Well, there’s the typical “cost of goods sold” - like customer support, hosting, and data feeds.

And then there’s the datacenter costs. A LOT of datacenter costs. Per the Information:

“Anthropic’s gross margin—gross profit as a percentage of revenue—was between 50% and 55% in December, according to two people with direct knowledge of the figures. That’s far lower than the average gross margin of 77% for cloud software stocks, according to Meritech Capital.”

And, depending on who you ask, it may not improve much over time: At least one major Anthropic shareholder expects the company’s long-term gross margin to be around 60%.

And that’s even before we throw in “the other stuff” that kinda sorta maybe should be contemplated:

“Notably, Anthropic’s gross margin doesn’t reflect the server costs of training AI models, which Anthropic includes in its research and development expenses. These costs can add up to as much as $100 million per model, according to Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI.”

I asked my buddy Fred Havemeyer, a leading sell-side equity analyst from Macquarie specializing in AI and software research, about the gross margin predicament in AI:

“What is the gross margin profile of generative AI? Will it be really cool, but just a cost center for businesses? I built my own model of a tier 4 data center model, bottom up…

…You can run bigger models with like a 60% plus gross margin.

You can run some mid sized models with much higher gross margins - like 80% plus gross margins.

And if you are running really small models… purpose built generative AI models, I estimate you can run them with 90% plus gross margins… very software like gross margins.

That gave me a lot of reassurance that this is not going to be a space that is just going to be a gross margin drag on these hyper scaler software businesses; that they can run profitably…”

What Fred said made me feel a little bit better. So I started searching for precedents. OpenAI, Anthropic, or [Insert Flashy AI Company Name] wouldn’t be the first to overcome these gross margin doubts.

The first name that comes to mind is Nvidia:

But if we’re being honest, for every Nvidia there’s an Intel:

What will separate the winners from the losers in the quest for “good” gross margins are their relationships with suppliers, most notably AWS / GCP / Azure on the cloud side, and chip manufacturers, like Nvidia, AMD, and Qualcomm.

Google and Amazon have already committed billions of dollars to Anthropic. And there are a handful of jokes that could be made about Microsoft actually running / owning OpenAI.

See - I even made a meme:

And while Nvidia is head and shoulders above the rest in terms of market share, it may not be necessary to purchase the Rolls Royce of chips to deliver the same services - AI developers may find it easier to run their models on cheaper servers. Or pull a Dropbox, and move in house entirely (epic reverse migration).

OpenAI and Wall Street Journal owner News Corp sign content deal

Deal lets ChatGPT maker use all articles from Wall Street Journal, New York Post, Times and Sunday Times for AI model development

ChatGPT developer OpenAI has signed a deal to bring news content from the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post, the Times and the Sunday Times to the artificial intelligence platform, the companies said on Wednesday. Neither party disclosed a dollar figure for the deal.

The deal will give OpenAI access to current and archived content from all of News Corp’s publications. The deal comes weeks after the AI heavyweight signed a deal with the Financial Times to license its content for the development of AI models. Earlier this year, OpenAI inked a similar contract with Axel Springer, the parent company of Business Insider and Politico.

Other publications, including the New York Times, have taken a different tack: suing OpenAI and Microsoft, the startup’s key backer, over the use of its content to train generative AI and large-language model systems.

News Corp is chaired by Lachlan Murdoch. His father, Rupert, serves as chairman emeritus stepping down as chair of News Corp and Fox News last year.

Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI, said: “Our partnership with News Corp is a proud moment for journalism and technology. We greatly value News Corp’s history as a leader in reporting breaking news around the world, and are excited to enhance our users’ access to its high-quality reporting.

“Together, we are setting the foundation for a future where AI deeply respects, enhances, and upholds the standards of world-class journalism.”

“We believe a historic agreement will set new standards for veracity, for virtue and for value in the digital age,” said Robert Thomson, chief executive of News Corp. “We are delighted to have found principled partners in Sam Altman and his trusty, talented team who understand the commercial and social significance of journalists and journalism.”

Scale AI Raises $1B In Accel-Led Round; Hits $13.8B Valuation

Chris Metinko, May 21, 2024

Scale AI raised $1 billion in a round led by Accel that values the data labeling and evaluation startup at a stunning $13.8 billion.

The valuation is nearly double the $7.3 billion the San Francisco-based startup hit after a $325 million raise in April 2021.

The new financing included some of the biggest names in tech, with Nvidia, Meta and Amazon all investing. Others existing investors participating in the round included Y Combinator, Nat Friedman, Index Ventures, Founders Fund, Coatue, Thrive Capital, Spark Capital, Tiger Global, Greenoaks Capital and Wellington Management, as well as new investors Cisco Investments, DFJ Growth, Intel Capital, ServiceNow Ventures, AMD Ventures, WCM Investment Management and Elad Gil.

The new Scale AI round is the second $1 billion raise for a U.S.-based AI startup this month, after CoreWeave raised a whopping $1.1 billion in a fresh funding round led by Coatue in a deal valuing the company at $19 billion, per The Wall Street Journal.

Scale AI plays a key role in creating large language models, accurately labeling text, images, video and voice data. The startup also creates and fine-tunes data sets.

That’s not all

However, that is not the only big deal Accel was in on Tuesday.

Paris-based artificial intelligence startup H has launched with a $220 million round. In previous reports, the company was called Holistic AI.

The startup, created by a former Google DeepMind scientist, is looking to create “multimodal-to-action” models capable of reasoning, planning and performing complex tasks.

The round included investment from the likes of Accel, UiPath, Bpifrance Large Venture, Eric Schmidt, Amazon and others.

..More

The Awful State of AI in California

Nathan Lands

Co-host of The Next Wave Podcast with Matt Wolfe & HubSpot | Founder of Lore.com, The Techno-Optimist AI Newsletter | Investor & Entrepreneur

May 22, 2024

1) The Awful State of AI in California

Today, California took a massive step backward by passing the ‘AI Safety & Innovation Bill’ in the Senate.

Senator Scott Wiener, infamous in my old home of San Francisco for pushing questionable legislation, has outdone himself.

Wild to see him gleefully cheering for the destruction of progress and prosperity in California.

I’d like to think he’s not doing it on purpose and doesn’t understand that he’s helping pass a bill that could choke the life out of open-source innovation in California.

Innovation Killing Bill

My understanding of the bill is that it essentially forces creators of large language models (LLMs) to sign under penalty of perjury that their LLMs can't cause harm…

How do we define harm?

Do we hold hammer makers accountable for the potential misuse of their tools?

It also makes it so that if your model could be modified to be dangerous, the model itself is considered dangerous. I’m no legal expert, but that sounds like a ban on open-source AI.

Silicon Valley Speaks Out

This is such an awful bill.

Weiner chooses to listen to two Canadian academics and a fringe group in Berkeley over many Ca. voices who will have to deal with this nonsense.

This is absolutely anti little tech, anti open source, and anti AI research and innovation.

Martin Casado, A16Z General Partner

Expecting developers to prevent “unsafe modification” or “malicious use” of an AI model. Requiring them to enable “full shutdown” of all copies of a model. This bill was either written by someone who doesn’t understand open source development or is determined to kill it.

Regulation’s 2nd & 3rd Order Effects

I always hear the argument that “planes are heavily regulated, and that’s why they don’t crash.” So, we should regulate AI. But planes weren’t heavily regulated at the beginning, were they?

Imagine if the Wright Brothers were prevented from conducting their flight experiments in the fields of Ohio. Because some clueless politician with no real-world experience was worried that their gravity-defying marvels might crash sometime.

What if they had to sign under penalty of perjury that their airplane experiments could cause no harm? We’d still be taking boats everywhere.

And without the invention of flying, there are so many things we wouldn’t have invented. Spaceships, rockets, satellites, solar panels, water purification systems, etc.

That’s the kind of thing these Senators aren’t thinking about. When you slow down technological progress, you prevent the invention of new things that move humanity forward. Which is the basis for our modern, thriving civilization.

We’re either moving forward, or we’re sliding backward.

Call To Arms

AI is a bigger invention than even the airplane. And we are just now at the beginning of its birth.

We have yet to discover all the progress and inventions it will bring to America and the world. We cannot allow this better future to be squandered by politicians who don't respect builders or understand the foundations upon which our society stands.

It's time for us to stand up, make our voices heard, and protect the future of AI innovation in Silicon Valley, no matter where you live.

I urge you to contact Governor Gavin Newsom's office to express your thoughts on this bill and protect innovation in California. You can also call his office at (916) 445-2841.

News Of the Week

It’s Time to Believe the AI Hype

Some pundits suggest generative AI stopped getting smarter. The explosive demos from OpenAI and Google that started the week show there’s plenty more disruption to come.

Tech pundits are fond of using the term “inflection points” to describe those rare moments when new technology wipes the board clean, opening up new threats and opportunities. But one might argue that in the past few years what used to be called out as an inflection point might now just be called “Monday.”

This is an excerpt from an edition of Steven Levy's Plaintext newsletter.

Certainly that applied this week. OpenAI, denying rumors that it would unveil either an AI-powered search product or its next-generation model GPT-5, instead announced something different, but nonetheless eye-popping, on Monday. It was a new flagship model called GPT-4o, to be made available for free, which uses input and output in various modes—text, speech, vision—for disturbingly natural interaction with humans. What struck many observers about the demo was how playful and even provocative the emotionally expressive chatbot was—but also imbued with the encyclopedic knowledge of data sets encompassing much of the world’s knowledge. CEO Sam Altman expressed the obvious in a one word tweet: “Her.” That movie—where the protagonist falls in love with a seductive, flirty chatbot—has been evoked endlessly of late. But the reference has a special kick when it comes from someone whose company has basically just built the damn thing like the screenplay was a blueprint. Also crazy was another demo posted by OpenAI that involved one chatbot scanning a scene with a camera and a second chatbot asking it questions. Poor Greg Brockman, the OpenAI cofounder running the demo, had to endure humiliation while the two robots exchanged views on his fashion and decor choices, and even taunted him with songs about it.

The 49-Year Unicorn Backlog

Joanna Glasner, jglasner, May 20, 2024

If the current sluggish pace of IPOs and acquisitions continues, it would take more than 49 years for every U.S. unicorn to generate an exit.

That was the finding from an analysis of recent exits for American companies on the Crunchbase Unicorn Board. Over the past 12 months, just 15 private, venture-backed companies valued at $1 billion more have gone public or gotten acquired.

Meanwhile, another 741 U.S.-based private, venture-backed companies remain in existence that met or exceeded the $1 billion threshold at their last reported valuation. If the exit tempo of the past 12 months stays the same, it would take just over 49 years to get through that backlog.

Recent historical perspective

Luckily, one constant in the startup world is that nothing stays the same. And given that exit activity has been slower than usual this past year, it’s reasonable to expect it will pick up.

Still, it’d take some NASCAR-level acceleration to get through a backlog this big. Even in 2021, the peak year on record, a total of 86 known unicorns carried out exits, per Crunchbase data. And that was pretty unusual.

Typically, the annual crop of unicorn exits is far smaller. For the past five years, it’s averaged 38 per year. At that pace, it would still take nearly 20 years to get through the current unicorn supply.

Not everyone exits

Of course, this is a theoretical exercise. No one expects every company once anointed with a coveted $1 billion-plus valuation will go on to exit. Some will fail, either shuttering and liquidating assets or filing for a bankruptcy reorganization.

In the past year, we’ve seen a number of private unicorns shut down or file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The list includes former high-flyers like trucking logistics startup Convoy, homebuilder Veev, and health benefits automation provider Olive AI.

Others could conceivably stay private indefinitely. SpaceX, the most valuable U.S. unicorn, has proven it’s possible to take this route and prosper. More broadly, a booming secondary marketfor shares in private companies has opened up a path to liquidity that doesn’t require a formal exit event.

Big exits make the difference

As for traditional exits, quality tends to matter more than quantity.

Startup investment is a hits business, and just a handful of standout success stories provide a lion’s share of returns for VCs.

In this respect, the past year hasn’t been too bad. Although startup IPO valuations haven’t broken any records, we have seen some pretty large public offerings and strong aftermarket performance.

..More

Humane, the creator of the $700 Ai Pin, is reportedly seeking a buyer

5:13 AM PDT • May 22, 2024

Humane, the company behind the much-hyped Ai Pin that launched to less-than-glowing reviews last month, is on the hunt for a buyer, Bloomberg reported, citing anonymous sources.

The company has reportedly priced itself between $750 million and $1 billion, and the sale process is in the early stages, Bloomberg cited the sources as saying.

Humane has never revealed an official valuation at any of its funding rounds, though The Information reported last year that its valuation was $850 million.

Humane did not immediately respond to requests for comment on the report.

..More

NVIDIA CRUSHES EARNINGS, AGAIN

May 23, 2024 · by D/D Advisors · in AI, Analyst Decoder Ring. ·

It is happening so regularly that things are starting to get boring. Nvidia reported strong earnings and above-consensus guidance for the quarter, again. Then CEO Jensen Huang got on the call, and the stock went up more on his commentary, again. The numbers: the company reported 1Q25 revenue of $26 billion and EPS of $5.59, ahead of consensus of $24.5 billion and $5.59. They guided 2Q25 revenue to $28 billion versus consensus of $26, and EPS of ~$6.30 versus $6.12. These are big numbers by any metric. Oh, they also announced a 10 for 1 stock split, catnip for retail investors.

It is hard to grasp how large and how quickly Nvidia has grown. Our preferred metric currently is Nvidia’s share of wallet for data center processors, looking at Nvidia, Intel and AMD’s reported data center revenue. That figure reached 81% in the quarter. They took a point of share from AMD and five points from Intel.

In fairness, Nvidia’s data center revenue includes networking products such as Infiniband. Conveniently, the company began breaking out their data center networking revenue. In theory, we should remove that from the calculation as neither AMD nor Intel have comparable products. That being said, that spend is coming from the same set of customers. And even stripping it out only takes their share to 78%. To put that in context, Arista, a company that only sells networking products, did $5.3 billion in revenue for all of 2023.

A few other things stood out for us on the call. The company claims they are now supplying 100 “AI Factories”, these are data centers operated independent of the hyperscalers. We wrote about these a few months back, and we remain somewhat cautious about the subject. There is nothing wrong with Nvidia’s numbers, but when there are we will likely see that telegraphed from this sector. It is worth noting that many of these AI factories turn around and re-sell capacity to the hyperscalers, which is a bit circular. We also are uncomfortable with the fact that Nvidia seems to have an extra-heavy hand with these companies. Nvidia is their major supplier, really the basis of their business model in these times of tight supply of GPUs. Nvidia also seems to sell their whole stack to them, complete systems, and likely designs them as well. On top of all that, Nvidia is likely an investor in many of them.

The company also added some color to their commentary about “Sovereign AI” which they are now defining as “a nation’s capabilities to produce AI using its own infrastructure”. The emphasis this quarter was on AI factories built in conjunction with telecom networks, such as Japan’s $740 million investment in a project led by telco KDDI, Sakura Internet and Softbank, to build up that country’s “AI Infrastructure”. This is another area that makes us a bit uncomfortable. A market segment built on government’s building Ai capabilities, it is all just a bit too vague. On the other hand, it is clearly generating a lot of revenue for the company.

Probably the most asked about topic on the call was the extent of demand. The company indicated they expect demand to outstrip supply well into next year. Going into the call, there were concerns that the company’s new Blackwell line of GPUs would cannibalize sales of the previous generation Hopper chips. The short answer to that is there does not seem to be a problem, with the company becoming even more supply constrained for certain Hopper products during the quarter. When asked how customers feel about current purchases when they see new products coming to market, Huang replied they will “Performance average their way into it.” Which is his way of saying customers will buy whatever they can get their hands on. We actually heard a better explanation today which goes along the lines that customers know Nvidia’s roadmap and are building plans around that. They will use B200 when they can get some and H100 when they can’t.

Startup of the Week

SUNO’S HIT FACTORY

Today, Lightspeed is announcing that we’re leading a Series B in Suno, the company that’s building a future where anyone can make music. Founded by lifelong musicians and aspiring technologists Mikey Shulman, Georg Kucsko, Martin Camacho, and Keenan Freyberg, Suno has now raised a total of $125M, enabling the team to accelerate the development of its state-of-the-art music creation model and consumption platform. We at Lightspeed are thrilled to support Suno on this next phase of their journey alongside other investors like Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross, Matrix, Founder Collective, Aravind Srinivas, Aaron Levie, Andrej Karpathy, Demi Guo, and other luminaries from AI, startups, and music.

The instrument anyone can play

All humans are inherently creative. Smartphones and the internet have made expressing that creativity much easier: Billions of people now create videos on platforms like YouTube, photos on platforms like Instagram, and writing on platforms like X. Each time a new medium becomes democratized, the potential for that medium expands, elevating both the existing creators in that space and inviting millions more to participate. Democratization of creativity also leads to market expansion, helping creators of all sizes – from pros to beginners – to earn money and potentially make a living off their art.

However, the creation of music, a medium that’s consumed by nearly everyone on the planet, remains inaccessible to most. But generative AI changes this equation. AI is yet another amazing innovation in the evolution of music creation, much like digital audio workstations, synthesizers, turntables, and electric guitars before it. At their introduction, each of those tools were decried as not being for “real musicians”, only to become mainstream and enable many more people to express themselves than before their existence.

Recent advancements in transformer and diffusion-based AI model architectures have made it possible for anyone to create music through the same types of inputs and devices that creators leverage to express themselves through other mediums. And while AI-powered music creation may be inevitable, Suno is the company leading the charge towards a future that enables anyone to create and share their work.

Lifelong musicians turned aspiring technologists

The Suno founders all met during their days at Kensho, the financial artificial intelligence company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Eventually, the four realized they had something else in common: a shared passion for making music, which ultimately inspired them to chase Suno’s mission together.

Warpcast of the Week

Be Generous

AVC, May 23, 2024

I am struck by the difference in approach taken by the top onchain entrepreneurs and the top entrepreneurs from earlier internet eras (web1 and web2).

The earlier internet eras have been marked by companies and founders focused on selfishness:

"Your margin is my opportunity" - Jeff Bezos

"You know, one of my favorite Roman orators ended every speech with the phrase Carthago delenda est--Carthage must be destroyed" - Mark Zuckerberg

But when I look at the top onchain entrepreneurs I see generosity:

The Satoshi mic drop is the greatest entrepreneurial act I have ever witnessed. They created what has become a 1.4 Trillion economy and then just walked away. They gave it to the world and said "it is yours".

Vitalik stuck around but has taken a similar approach. He has welcomed other entrepreneurs to create systems that take value away from the Ethereum blockchain. I would say he has even encouraged it.

How can giving something away or letting others take value from you be good business?

It is all about zero sum thinking. If you think that the size of the pie is fixed, then you need to grab as much of it as you can. But if you are making a pie that can grow and grow and grow, you just take a small slice and let everyone else eat.

That is the Satoshi mic drop.

And it is the key to winning onchain.

Don't be selfish.

Be generous.

![Illustration of stopwatch - AI [Dom Guzman] Illustration of stopwatch - AI [Dom Guzman]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!mWCE!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F52eabc18-b9cc-4464-8651-9c5c2dc2c485_900x506.jpeg)