Contents

Editorial: The Year of Intelligence: Why No One Is “Winning” the AI Race Yet

Essay

AI

Warner Music signs deal with AI music startup Suno, settles lawsuit

Ilya Sutskever – We’re moving from the age of scaling to the age of research

What to know about Trump’s order for the AI project ‘Genesis Mission’

Base44’s Founder, Maor Shlomo on Why Vibe Coding Has No Defensibility

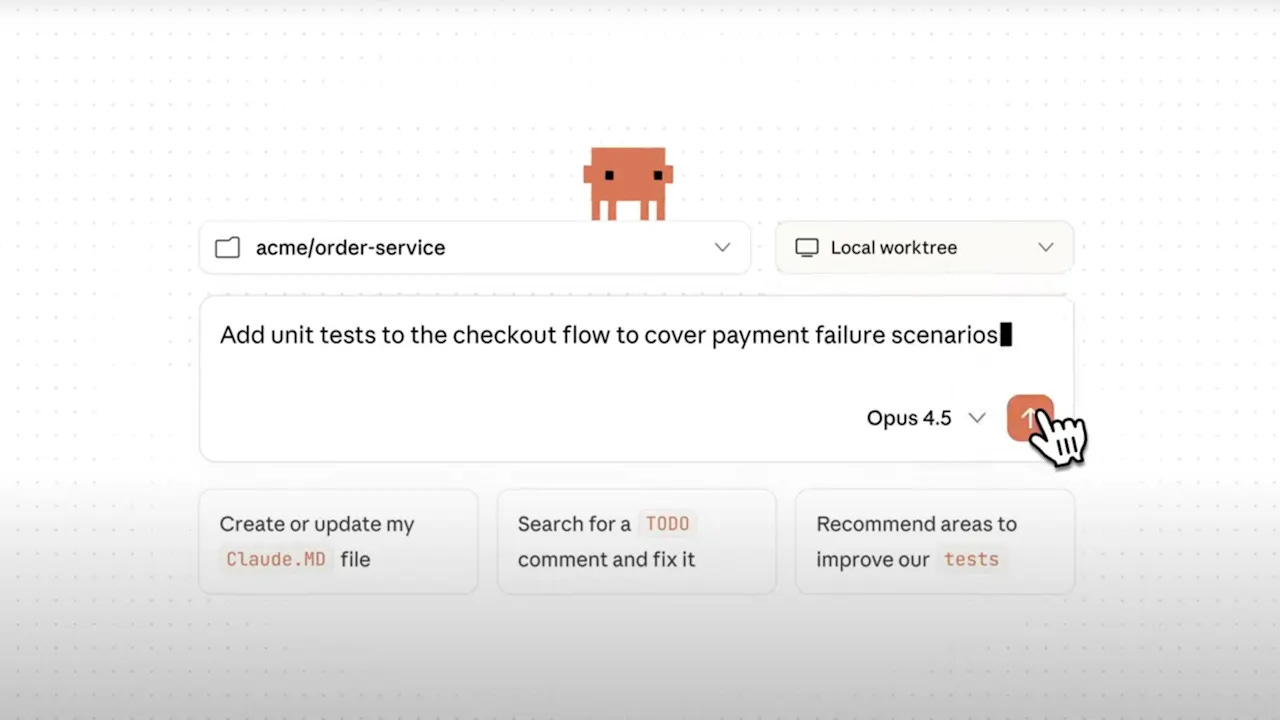

With new Opus 4.5 model, Anthropic’s Claude could remain the best AI coding tool

OpenAI needs to raise at least $207bn by 2030 so it can continue to lose money, HSBC estimates

Leonardo Unveils AI-Driven System to Defend Cities From Attack

Nvidia Earnings; Power, Scarcity, and Marginal Costs; OpenAI Hand-wringing

China

Venture

Education

GeoPolitics

Editorial: The Year of Intelligence: Why No One Is “Winning” the AI Race Yet

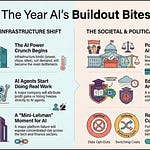

If you only read the headlines this week, you’d think Google had already won the AI race. Gemini 3 benchmarks, Nvidia’s earnings, and endless talk of “AI bubbles” paint a picture of a single triumphant stack.

But when we zoom out across this week’s stories, a different pattern emerges: we’re not in the year of Gemini; we’re in the year of intelligence itself.

On coding and agents, Anthropic and OpenAI quietly rewrote the script. Claude Opus 4.5 now tops SWE‑bench, agentic coding, and ARC‑AGI‑2, with customers reporting 20% accuracy and 15% efficiency gains on real Excel workflows. GPT‑5.1 Codex‑Max pushes automated software engineering further: higher SWE‑bench‑verified scores, hours‑long persistence on METR’s “AI 2027” graph, and meaningful jumps on internal AI‑R&D tasks like Paperbench‑10 and MLE‑Bench. Gemini 3 Pro is impressive—but it is one curve on a crowded chart, not the finish line.

When Anthropic can credibly say Opus 4.5 is the “best model in the world for powering agents,” and Zvi’s analysis of Codex‑Max still points to incremental, not explosive, timelines, the idea that Google has structurally “pulled ahead” looks more like marketing than reality.

Meanwhile, the ecosystem is fragmenting in ways that favor no single winner: - China’s open‑weight push is leapfrogging US incumbents in downloads and developer mindshare. Open models like Qwen are becoming default infrastructure across the Global South, while Chinese giants move training offshore to access Nvidia chips despite US export controls. I

f your AI worldview starts and ends in Mountain View, you’re missing half the board. - HSBC’s estimate that OpenAI must raise $207bn by 2030 crystallizes the capital intensity of staying at the frontier.

Nvidia’s blowout earnings, Ben Thompson notes, tell us less about bubbles and more about a new industrial stack where power and data centers are the constraint.

“To that end, I think the hand-wringing about OpenAI in particular has gotten a bit out of hand over the last few days. For one, now that people are putting Gemini 3 through its paces, it’s clear it’s not a perfect model; in particular, it seems to hallucinate much more than GPT 5.1 Thinking, and it’s not very good at following directions.

Indeed, per the point above, the biggest improvements do seem directly downstream from the sheer size and associated compute that went into developing it; that not only reiterates the bull case for Nvidia, but also suggests that upcoming models from OpenAI (and Anthropic and xAI, for that matter) should see big leaps as well, especially the ones that are trained on Blackwell (GPT-5 was trained on Hopper).”

This is not a tidy “Google vs OpenAI” duel; it’s a trillion‑dollar build‑out where governments (Trump’s Genesis Mission), sovereign wealth funds, and retail‑oriented CEFs are all piling in. - Venture plumbing is mutating to match.

Meanwhile there are seismic changes in later stage Venture Capital, especially regarding liquidity.

Closed‑end funds, secondaries as a first‑class tool, and brutal VenCap data (only 6% of funds ever hit 5x) tell us that LPs are trying to surf this wave without drowning in illiquidity or hype.

Bubble talk hasn’t slowed term sheets on Sand Hill; it has just forced better structures. At the same time, the “AI vs creators” panic is giving way to negotiated coexistence.

Platformer’s “AI is winning the copyright fight” and Warner Music’s settlements with Suno and Udio point the same way: labels are folding courtroom maximalism into licensing deals. Training goes on; artists get some knobs and some cash.

As with PopEVE in rare‑disease genomics or Apple‑backed rural classrooms in Alabama, the real story is deployment: AI as infrastructure for diagnosis, education, and culture, not an apocalypse.

The deeper parallel belongs to the Enlightenment thread this week: Britain’s rise wasn’t just steam and coal; it was a cultural shift toward belief in progress. Our version is playing out in real time.

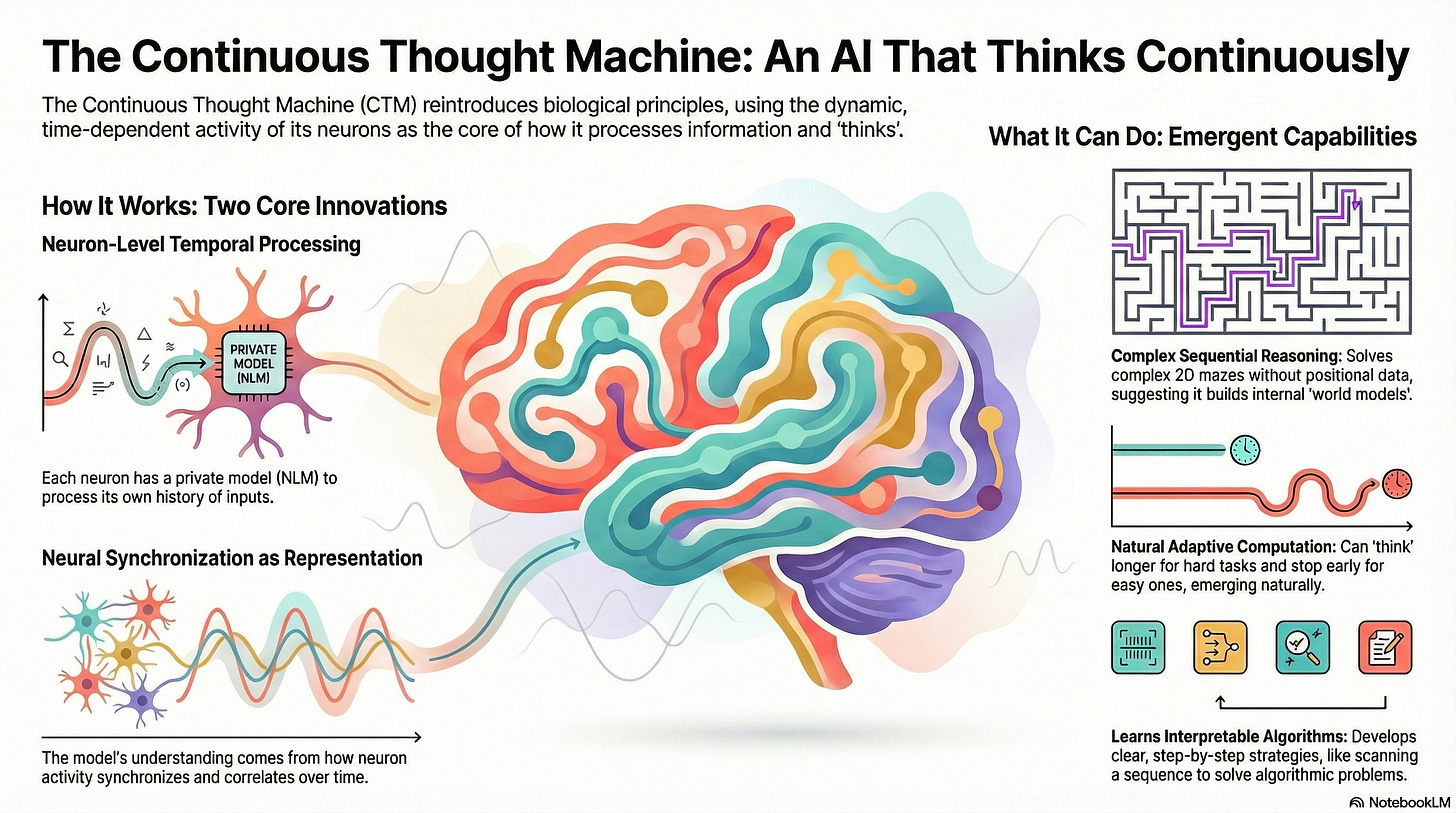

Look at Sutskever’s interview about the “age of research”, acknowledging that scaling alone isn’t enough to get to “reliable generalization”, to Sakana.ai’s white paper on “Continuous Thinking Machines”. There are significant new technologies being developed and not yet at the product stage. Demis Habassis at DeepMind concurs with the need for generalization too.

And add to that Beckert’s reminder that capitalism is historical, not natural, we’re being handed the same political choice: do we oppose Sam Altman, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Elon Musk, and the rest, and cloud tech companies, from driving the gains because we don’t like rich people or big companies? Or do we embrace that capitalism is the only way to get these gains feeding global wealth? Do we use these productivity gains to shorten the workweek and broaden prosperity? And do we build policy based wealth distribution models that benefit from the gains AI will deliver?

The models are getting smarter; it is also likely that we will.

Looking ahead, we should stop asking “Will Google win?” and start tracking three harder questions:

Capabilities: Do agentic systems like Opus 4.5 and Codex‑Max start closing real human bottlenecks in R&D, not just coding demos?

Capital: Do structures like CEFs, secondaries, and public co‑ownership tame a $200tn asset world, or simply repackage risk for retail?

Civics: Can projects like Genesis Mission and the Suno/Warner deals become templates—where the state, creators, and capital share upside—rather than one‑off headlines?

This really is the year of intelligence. Not Google’s intelligence, or OpenAI’s, or China’s—but ours, in deciding what we do with it. A belief in ‘progress’ is foundational to human outcomes.

Essay

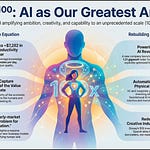

Maybe the S&P 500 will triple?

Ft • November 24, 2025

Essay•Venture

Headline View: Equities Far From Bubble Territory

The article explores the argument that US equities, and the S&P 500 in particular, may have substantial room to run and are “not even close” to bubble territory, despite record highs and widespread anxiety about stretched valuations. Drawing on analysis associated with Stephen Miran’s former firm, it contrasts popular bubble narratives with a more sanguine, fundamentals-based view suggesting that earnings power, real interest rates and structural factors could justify significantly higher index levels—potentially even a tripling over the coming decade under optimistic but coherent assumptions. The central theme is that what looks expensive on crude metrics may be reasonable once you account for sector mix, profitability and the macro backdrop.

Valuations in Context, Not in Isolation

The piece emphasises that headline valuation ratios like simple price/earnings or price/book can overstate froth when they ignore the changing composition of the S&P 500, especially the dominance of highly profitable, asset‑light technology and platform companies.

Compared with historical bubbles such as 1999–2000, earnings quality today is stronger, balance sheets cleaner and cashflow more robust; many of the largest index constituents generate substantial free cash flow and operate with net cash, weakening the analogy to prior manias.

Adjusting for real interest rates and risk premia, current equity risk premiums may not be unusually compressed. From this lens, equities can appear fairly valued or even modestly cheap relative to high‑quality bonds, particularly if inflation is contained and real growth proves resilient.

Macro Drivers of Potential Further Gains

The argument that the S&P 500 could plausibly triple rests in part on sustained nominal GDP growth, continued productivity gains and persistent profitability for dominant firms.

Structural supports mentioned include:

Ongoing digitisation and AI‑driven efficiency improvements that can expand margins and address labour constraints.

The global savings glut and regulatory frameworks that keep large institutional allocations tilted towards equities over the long run.

The relative scarcity of high‑yielding safe assets, which channels flows toward risk assets and compresses discount rates applied to future earnings.

Miran’s old shop effectively contends that if earnings grow at a healthy compound rate and valuation multiples merely hold steady—or expand moderately—the arithmetic of a multiple‑decade bull market implies markedly higher index levels without invoking bubble logic.

Why ‘Bubble’ May Be the Wrong Framing

Bubble talk is portrayed as more psychological than analytical: investors scarred by past crashes may be inclined to see any strong rally as inherently unsustainable.

The article suggests that, unlike in classic bubbles, there is no pervasive reliance on leverage among households nor a dominant narrative of guaranteed quick riches; instead, scepticism remains high and flows into equities are far from euphoric blow‑off patterns.

The concentration of returns in a handful of mega‑cap names is acknowledged, but argued to be grounded in demonstrable economic moats, network effects and recurring revenues rather than purely speculative enthusiasm.

Risks, Caveats and Investor Implications

While dismissing imminent bubble risk, the piece does not deny cyclical downside: earnings recessions, policy errors by central banks or geopolitical shocks could all generate substantial drawdowns.

It also hints at distributional risk within the index: leadership could rotate, and not all high‑multiple names will justify their valuations, even if the aggregate index performs well.

For investors, the main implication is that automatically de‑risking solely on the basis of index level or historical valuation charts may be misguided. A focus on cashflow durability, balance sheet strength and pricing power may be more sensible than attempting to time a perceived “top”.

Broadly, the analysis encourages viewing current valuations as a starting point for long‑term compounding, rather than a late‑stage bubble to be exited at all costs, keeping in mind that secular bull markets often advance much further—and last much longer—than most participants expect.

Enlightenment ideas and the belief in progress leading up to the Industrial Revolution

Marginal Revolution • November 23, 2025

Essay•Education•Enlightenment•Industrial Revolution•Cultural History

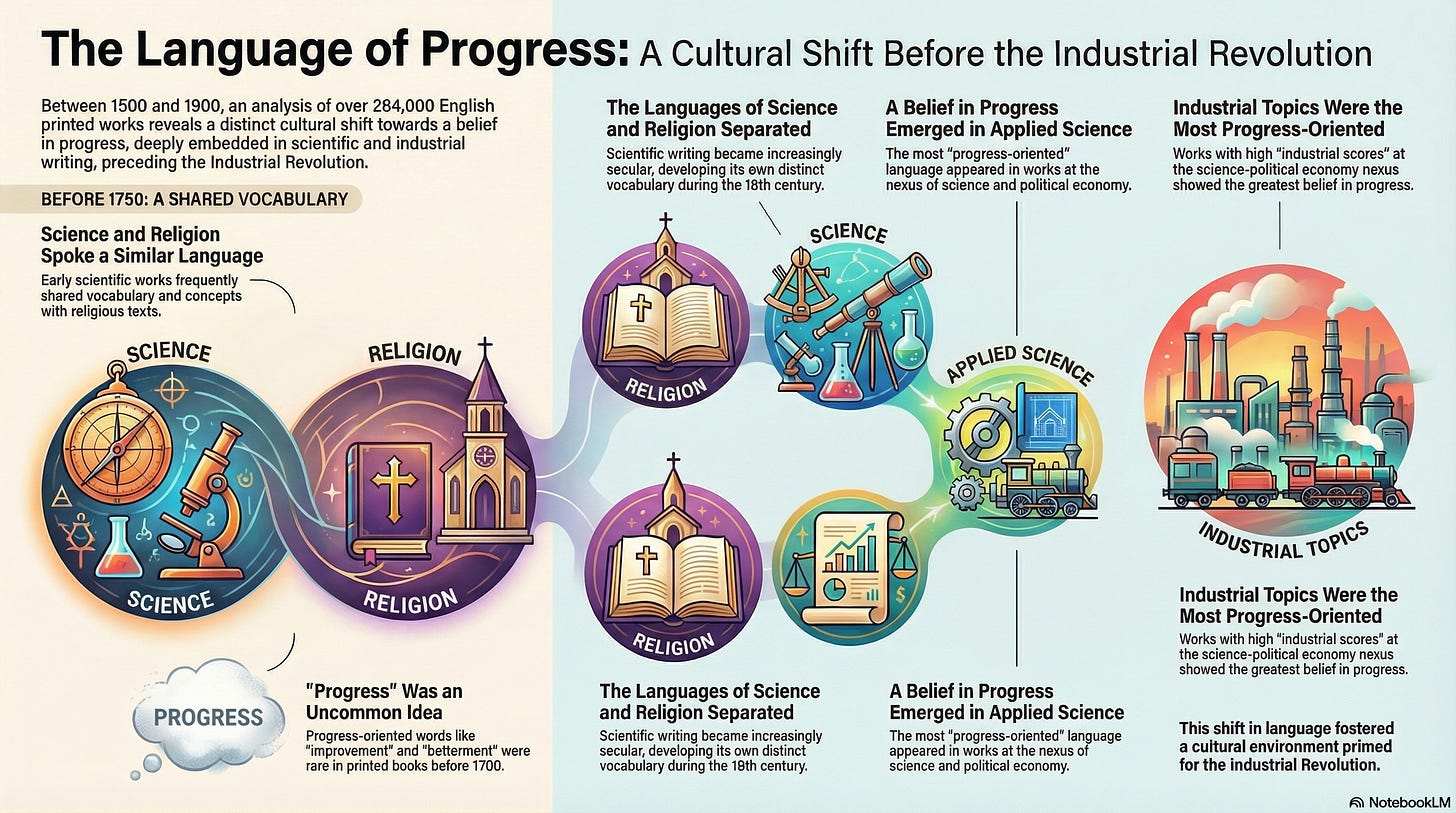

Overview of the Study and Central Question

The piece summarizes a study that uses large-scale textual analysis to investigate how British culture’s belief in progress evolved between 1500 and 1900. The central question is whether the rise of science and industry before and during the Industrial Revolution was accompanied by a measurable cultural shift toward ideas of progress, improvement, and human advancement. Researchers analyze 173,031 printed works from England to trace how language relating to science, religion, and progress changed over four centuries, using these linguistic trends as a proxy for underlying beliefs and values.

Methodology and Scope

The study covers printed works across a 400‑year span, from early modern England through the Victorian era.

It employs textual analysis, likely involving word frequencies, co-occurrence patterns, and semantic fields related to science, religion, and notions of progress.

By aggregating such a large corpus, the researchers aim to move beyond anecdotal examples of Enlightenment thinking and instead quantify broad cultural trends.

The time frame allows them to track changes before, during, and after the Industrial Revolution, offering insight into whether belief in progress preceded, accompanied, or followed industrialization.

First Key Finding: Separation of Science and Religion

The first main finding is a discernible separation in the language of science and religion beginning in the 17th century.

This suggests that terms, concepts, and discourse associated with scientific inquiry increasingly diverged from religious vocabulary.

Prior to the 17th century, much intellectual life in England mixed theology, natural philosophy, and moral reasoning; the observed separation indicates that science began to develop its own conceptual and linguistic domain.

This linguistic divergence aligns with broader historical narratives of the Scientific Revolution, the rise of experimental philosophy, and the emergence of scientific societies and specialized discourse.

The separation implies that British culture was gradually moving from a unified religious worldview toward a more differentiated intellectual landscape in which scientific and religious domains could be discussed independently and sometimes in tension.

Implications for Enlightenment Thought and Industrialization

The separation of science and religion in language can be interpreted as one dimension of Enlightenment thought: an increased emphasis on empirical inquiry, secular explanation, and the autonomy of human reason.

As science and industry became more central to economic and social life, a belief in progress—material, technological, and intellectual—likely gained cultural legitimacy.

The study’s broader project, hinted at by the article, is to see whether rising references to science, technology, and improvement in texts prefigured or paralleled the Industrial Revolution.

If belief in progress can be seen growing in the textual record before industrial takeoff, it would support the argument that cultural change and expectations about human improvement were not just a consequence of economic growth, but a contributing cause.

Broader Significance and Research Contribution

This research contributes to ongoing debates about why the Industrial Revolution first emerged in Britain rather than elsewhere.

By quantifying cultural attitudes, it provides empirical support for theories that emphasize ideas—such as faith in progress, rationality, and innovation—alongside more familiar explanations like resources, institutions, and geography.

The scale of the dataset (over 173,000 works) allows for a more systematic picture of cultural evolution than traditional intellectual history, which often focuses on a small canon of famous writers.

The finding that scientific and religious language began to diverge in the 17th century suggests that cultural groundwork for industrialization was being laid well before the classic Industrial Revolution period of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Key Takeaways

A massive corpus of English printed works from 1500–1900 is used to trace cultural beliefs about progress.

The first major result is the early modern separation of scientific and religious language starting in the 17th century.

This linguistic shift supports the view that Enlightenment ideas and a belief in secular, scientific progress emerged before and helped set the stage for industrialization.

The study reinforces the importance of cultural and ideological change in explaining Britain’s distinctive economic trajectory.

From Feudal Lords to AI Billionaires: Capitalism’s Thousand-Year Conquest of the World

Keenon • Andrew Keen • November 27, 2025

Essay•AI•Capitalism•Economic History•Wealth Inequality•Interview of the Week

Harvard historian Sven Beckert has published a new 1,100-page book entitled Capitalism: A Global History, a magisterial history that took eight years to write and covers the last thousand years of our increasingly dominant capitalist world. Beckert suggests capitalism has become so ubiquitous that most of us can’t imagine an alternative economic system. If we are fish, then it’s our water.

The article presents five key takeaways from Beckert’s work:

1. Capitalism Isn’t Natural—It’s Historical Capitalism is a radical departure from previous forms of economic life, not the default state of human exchange. Because it’s historical, it had a beginning—and anything with a beginning can have an end. 2. The Death of Capitalism Has Been Wrongly Predicted for 200 Years From Marx onward, critics have forecast capitalism’s imminent collapse. Beckert is skeptical of these predictions—most of capitalism’s history came after someone declared it finished. 3. There’s No Going Back to the Pre-Capitalist Village The nostalgic alternative—returning to some pre-modern arrangement—is both impossible and undesirable. Feudal lords extracting surplus from peasants, subsistence farming at the margins of survival: there’s nothing romantic about scarcity and exploitation. 4. We Have the Means to Solve Our Problems—We Lack the Political Will The capitalist revolution has given us unprecedented productive capacity. We could feed everyone, educate everyone, provide universal healthcare. The obstacles aren’t material—they’re political choices. 5. AI Could Liberate Us or Concentrate Wealth Further—It’s a Political Decision If artificial intelligence delivers massive productivity gains, those gains could go to a tiny elite or be distributed broadly through shorter work weeks, better wages, expanded education. The technology doesn’t determine the outcome. We do.

The Writer Who Dared Criticize Silicon Valley

Nytimes • November 27, 2025

Essay•Media•Silicon Valley•Libertarianism•TechCritique

Overview of the Argument and Its Renewal

The article discusses the renewed attention to Paulina Borsook’s book “Cyberselfish,” a work that, 25 years ago, offered stark warnings about the cultural and political consequences of Silicon Valley’s embrace of libertarian ideology. Borsook argued that the prevailing mindset in the tech world—hostile to government, obsessed with efficiency, and impatient with social obligations—would reshape not just the industry but the broader society in troubling ways. At the time of publication, her critique was largely dismissed as shrill, out of step, or simply “anti-tech.” Today, however, a new generation of readers is rediscovering the book and finding its analysis eerily prescient in light of Big Tech’s power and the social costs of the digital economy.

Core Ideas in “Cyberselfish”

Borsook contends that Silicon Valley’s libertarianism is not just an economic philosophy but a cultural disposition: an individualistic, anti-regulatory worldview that celebrates disruption while ignoring collective responsibilities.

She describes a tech elite that treats government and public institutions as obsolete “legacy systems,” while casting themselves as rational, superior problem-solvers who don’t owe much to the societies in which they operate.

The book warns that this worldview, if left unchecked, would erode social safety nets, weaken labor protections, and encourage a politics that valorizes wealth and technical prowess over democratic accountability or empathy.

Why the Book Is Resonating Now

Over the last quarter-century, many of Borsook’s “dire predictions” have, in the eyes of contemporary readers, materialized: the rise of billionaire tech founders as political actors, the concentration of digital power in a few platforms, and the growing gap between the fortunes of tech workers and everyone else.

The renewed interest is driven by ongoing public debates over content moderation, antitrust actions, AI regulation, and the cultural influence of figures who openly espouse libertarian or techno-utopian ideas.

Younger readers, facing precarious work, platform monopolies, and algorithmic management, see in “Cyberselfish” an early diagnosis of problems that now define their everyday lives.

Cultural and Political Implications

The article emphasizes that Borsook’s work is not simply an “I told you so” document but an attempt to show how ideology, culture, and personality types in the tech world bleed into policy and institutions.

It highlights the tension between the rhetoric of “making the world a better place” and a persistent refusal to engage with questions of inequality, taxation, and democratic oversight.

The renewed readership suggests a broader shift in how the public and policymakers view Silicon Valley: from heroic innovators to powerful industries deserving of scrutiny and restraint.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

“Cyberselfish” is increasingly seen as part of a canon of early tech criticism that anticipated surveillance capitalism, the gig economy, and the fragility of digital public spheres.

The article suggests that Borsook’s work helps readers understand that the problems of today’s tech landscape are not accidents of code or business models but outgrowths of long-standing ideological choices.

Its resurgence implies that serious, values-focused criticism of the tech world—once niche and marginal—is becoming central to how society interprets Silicon Valley’s role and responsibilities.

Key Takeaways

A long-overlooked critique of tech libertarianism is gaining new relevance in an era of Big Tech dominance.

The ideological underpinnings of Silicon Valley, rather than just its products, are crucial to understanding current political and economic tensions.

Revisiting works like “Cyberselfish” encourages a more historically grounded, less mythologized understanding of technological progress and its costs.

AI

AI is winning the copyright fight

Platformer • November 25, 2025

AI•Publishing•Copyright•Music Industry•Generative AI

Overview

The visible portion of the article signals a central argument: major music labels are starting to retreat or “fold” in their copyright battles against AI music startups. The theme is that, despite aggressive initial posturing from rights holders, structural and legal dynamics are pushing outcomes in favor of AI companies, at least for now. This reflects a broader shift in how copyright law interacts with generative AI, especially in music, where training data, style emulation, and synthetic vocals are colliding with long‑standing industry control over catalogues and artist likenesses.

Music Labels’ Strategy and Retreat

The article frames music labels as having pursued an assertive enforcement strategy against AI services that can generate music “in the style of” popular artists or emulate their voices.

However, the current situation is described as one where these labels are backing down in specific cases, indicating that negotiated settlements or strategic withdrawals are more common than clear courtroom victories.

By highlighting that labels are “folding,” the piece suggests that the legal terrain is more favorable to AI startups than rights holders publicly anticipated, or that labels fear setting broad, unfavorable precedents if cases proceed to judgment.

Why AI Startups Have the Advantage

The argument implies that AI companies benefit from ambiguity in existing copyright law around training data: large models often ingest public audio without explicit licenses, betting that this will ultimately be considered fair use or at least not clearly illegal.

Labels face a high bar to prove direct infringement when AI systems produce novel outputs rather than straightforward copies, especially if companies employ guardrails or filtering to avoid verbatim replication of protected works.

AI startups can often move faster and iterate on business models while litigation drags on, making early, quiet settlements appealing to rights holders that might otherwise prefer aggressive public enforcement.

Structural Weaknesses in the Labels’ Legal Position

The piece hints that courts and regulators have not yet clearly endorsed the labels’ most expansive theories of liability—for example, that training on copyrighted recordings alone constitutes infringement, or that stylistic imitation is inherently unlawful.

By contrast, U.S. law historically distinguishes between protecting specific expressions (recordings, compositions) and allowing others to freely draw on general style, genre, or “influence,” which may constrain the labels’ ability to argue against AI systems that generate sound‑alike tracks.

The presence of paywalled content suggests there are likely concrete examples—such as specific lawsuits, settlements, or abandoned actions—that illustrate these weaknesses in practice, though they are not fully visible.

Implications for Artists and the Music Industry

The article’s framing implies a growing imbalance between the interests of artists and labels on one side and technology firms on the other. If AI music companies emerge with favorable settlements or avoid adverse judgments, artists may see their styles and voices emulated with limited recourse.

This dynamic could accelerate a flood of AI‑generated music, undermining traditional revenue models tied to catalog control and exclusive recording rights, and forcing labels to consider licensing their libraries for training rather than trying to block it entirely.

At the same time, labels’ retreat may push artists to seek new contractual protections, lobbying efforts, or alternative rights structures that deal explicitly with AI training and synthetic performance rights.

Broader Context for AI and Copyright

The article situates these music disputes in a larger pattern: across creative industries, early lawsuits against generative AI have struggled to establish clear, sweeping prohibitions on training or output. The visible text about other Platformer pieces—on the FTC, California’s platform law, and AI regulation—suggests an editorial through‑line: AI is testing the boundaries of existing legal frameworks faster than regulators or courts can respond.

This trend may normalize AI’s presence in culture and weaken the deterrent power of copyright threats. Once a few large players reach settlements that let AI training continue under certain conditions, smaller labels and artists may find it harder to resist similar deals.

Key Takeaways

Music labels’ initial legal offensives against AI music startups are not producing the decisive wins many expected; instead, they are often settling or backing away.

Ambiguities around training data, style emulation, and fair use create a strategic advantage for AI companies, which can keep innovating while legal questions remain unsettled.

The retreat of labels in these early test cases has deep implications for artists’ control over their sound and likeness, and for the future economics of recorded music.

More broadly, the situation exemplifies how generative AI is “winning” early copyright battles, shaping a default environment where training on creative works proceeds unless and until lawmakers intervene with new rules.

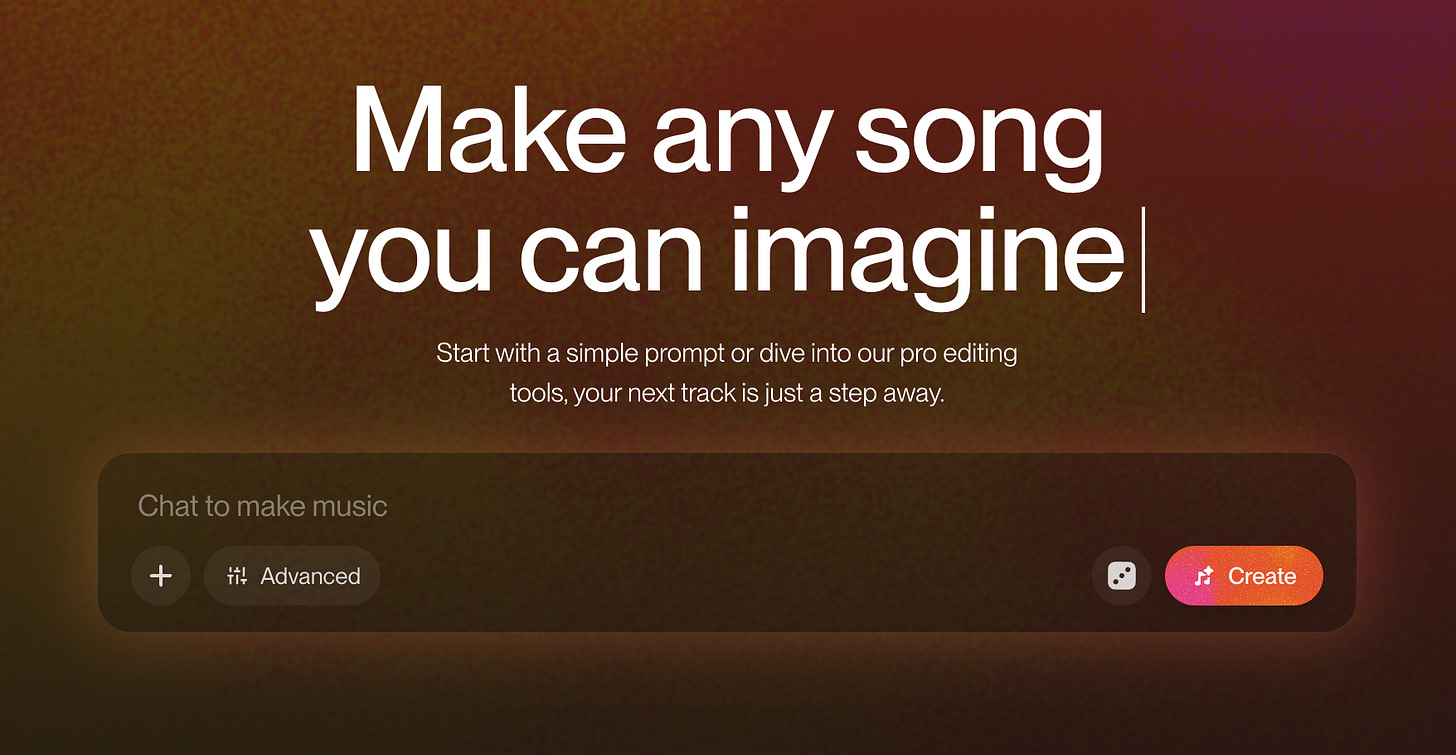

Warner Music signs deal with AI music startup Suno, settles lawsuit

Techcrunch • Aisha Malik • November 25, 2025

AI•Tech•MusicIndustry•Suno•WarnerMusic

Warner Music Group (WMG) announced that it has reached a deal with Suno, settling its copyright lawsuit against the AI music startup. WMG said in a press release that the deal with Suno will “open new frontiers in music creation, interaction, and discovery, while both compensating and protecting artists, songwriters, and the wider creative community.”

WMG also announced that it has sold Songkick, a live music and concert-discovery platform, to Suno for an undisclosed amount. WMG had acquired Songkick’s app and brand in 2017, while Live Nation later acquired Songkick’s ticketing business.

WMG says Songkick will continue as a fan destination under Suno.

As a result of WMG’s partnership, Suno will launch more advanced and licensed models that will replace its current ones next year. Downloading audio from the service will require a paid account, while users on the free tier will be limited to playing and sharing songs made on the platform.

WMG says artists and songwriters will have full control over whether and how their names, images, likenesses, voices, and compositions are used in new AI-generated music.

Artists signed to WMG include Lady Gaga, Coldplay, The Weeknd, Sabrina Carpenter, and more.

“This landmark pact with Suno is a victory for the creative community that benefits everyone,” said WMG CEO Robert Kyncl in the press release. “With Suno rapidly scaling, both in users and monetization, we’ve seized this opportunity to shape models that expand revenue and deliver new fan experiences.”

The news comes a week after WMG settled its copyright lawsuit with AI music startup Udio and entered into a licensing deal for an AI music creation service that’s set to launch in 2026.

WMG’s settlements with Suno and Udio mark a significant shift in the music industry’s approach to AI.

Ilya Sutskever – We’re moving from the age of scaling to the age of research

Dwarkesh • November 25, 2025

AI•Tech•Generalization•DeepLearning•AIResearch

Overview

The central claim is that today’s large AI models, despite their impressive capabilities, still “generalize dramatically worse than people.” This gap in generalization is presented as a deeply fundamental limitation of current systems that rely heavily on scaling up data and compute. The quote suggests that while models can interpolate within the patterns they have seen during training, they struggle with the kind of robust, flexible understanding that humans routinely display when confronted with new situations, sparse data, or distributional shifts.

Limits of Current Generalization

The remark highlights that models often fail in ways humans typically do not: brittle behavior on slightly out-of-distribution inputs, susceptibility to adversarial prompts, and overconfident errors.

Human generalization is portrayed as being built on rich world models, causal reasoning, and the ability to rapidly adapt from very few examples, whereas current AI tends to rely on statistical pattern matching at massive scale.

The “very fundamental thing” alludes to the idea that no matter how large or powerful current architectures become, they may remain constrained by their training paradigm and objective functions, rather than gaining genuinely human-like understanding.

From Scaling to Research

Implicit in the quote is a transition in emphasis: scaling alone is no longer sufficient to close the gap in generalization relative to humans.

Moving to an “age of research” means focusing on new architectures, training objectives, forms of data, and perhaps new theoretical insights that specifically target generalization rather than just performance benchmarks.

This involves asking deeper questions: What inductive biases are needed for human-like reasoning? How do we represent and manipulate abstract concepts, causal structure, and goals in a way that is robust under change?

Human vs. Machine Learning Dynamics

People routinely generalize from extremely small datasets: one or two demonstrations can suffice to learn a new skill or concept, often in entirely new contexts.

Current large models, by contrast, require vast amounts of data to reach comparable surface-level performance and still falter when context shifts or when they face tasks requiring commonsense grounding.

The quote underscores that this discrepancy is not a minor detail but sits at the heart of what makes current systems different from human minds.

Implications for Future AI Development

If models “generalize dramatically worse than people,” then simply adding more parameters and tokens will hit diminishing returns on safety, reliability, and real-world robustness.

This has practical consequences for deploying AI in high-stakes domains: systems must be able to handle rare events, novel edge cases, and subtle shifts in environment — all areas where human generalization is currently superior.

It also suggests a research agenda focused on:

Better representations of the real world and causal structure

More human-like learning mechanisms (few-shot, continual, and curriculum learning)

Alignment techniques that ensure generalization of values and constraints, not just behavior on training distributions

Broader Significance

The quote can be read as both a critique and a motivation: today’s models are impressive but incomplete; their limitations in generalization are a roadmap for what the next era of AI research must address.

Bridging the gap between statistical generalization and human-like understanding is framed as a central challenge for the field, one that will likely require conceptual breakthroughs rather than incremental scaling.

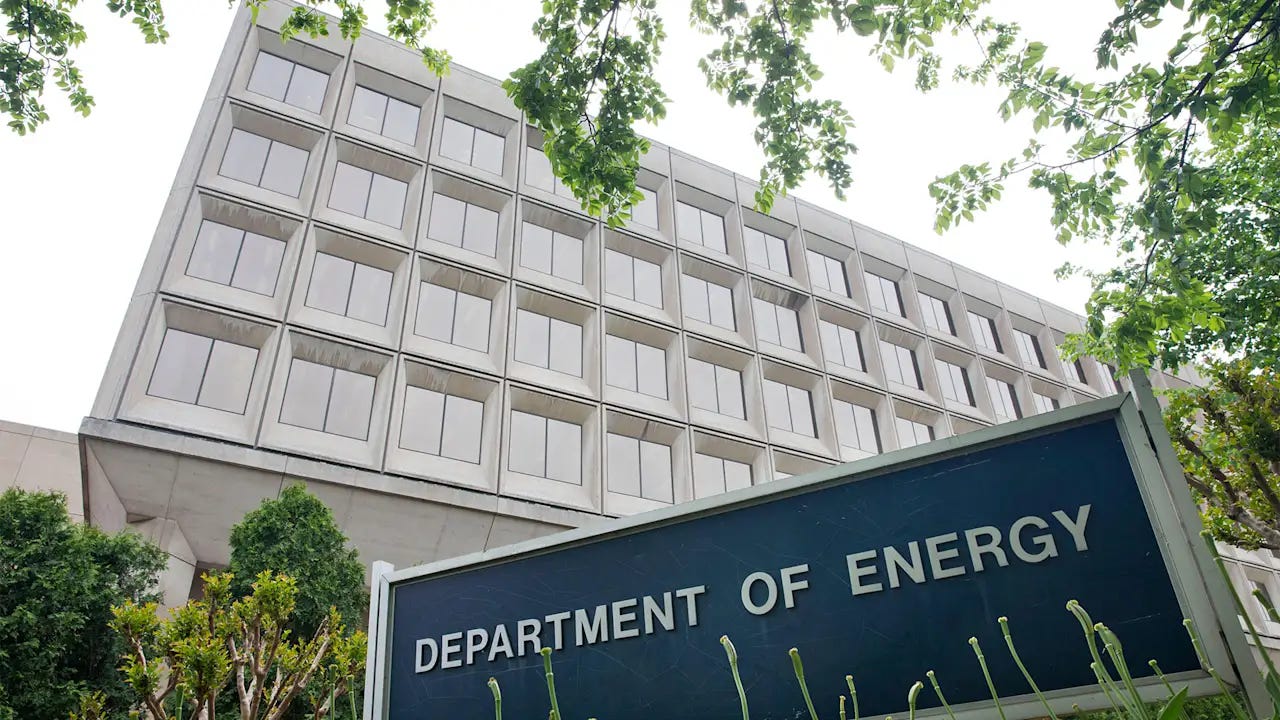

What to know about Trump’s order for the AI project ‘Genesis Mission’

Fastcompany • November 25, 2025

AI•Tech•GenesisMission•EnergyDepartment•DataCenters

President Donald Trump is directing the federal government to combine efforts with tech companies and universities to convert government datainto scientific discoveries, acting on his push to make artificial intelligencethe engine of the nation’s economic future.

Trump unveiled the “Genesis Mission” as part of an executive order he signed Monday that directs the Department of Energy and national labs to build a digital platform to concentrate the nation’s scientific data in one place.

It solicits private sector and university partners to use their AI capability to help the government solve engineering, energy and national security problems, including streamlining the nation’s electric grid, according to White House officials who spoke to reporters on condition of anonymity to describe the order before it was signed. Officials made no specific mention of seeking medical advances as part of the project.

“The Genesis Mission will bring together our Nation’s research and development resources — combining the efforts of brilliant American scientists, including those at our national laboratories, with pioneering American businesses; world-renowned universities; and existing research infrastructure, data repositories, production plants, and national security sites — to achieve dramatic acceleration in AI development and utilization,” the executive order says.

The administration portrayed the effort as the government’s most ambitious marshaling of federal scientific resources since the Apollo space missions of the late 1960s and early 1970s, even as it had cut billions of dollars in federal funding for scientific research and thousands of scientists had lost their jobs and funding.

Trump is increasingly counting on the tech sector and the development of AI to power the U.S. economy, made clear last week as he hosted Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The monarch has committed to investing $1 trillion, largely from the Arab nation’s oil and natural gas reserves, to pivot his nation into becoming an AI data hub.

For the U.S.’s part, funding was appropriated to the Energy Department as part of the massive tax-break and spending bill signed into law by Trump in July, White House officials said.

As AI raises concerns that its heavy use of electricity may be contributing to higher utility rates in the nearer term, which is a political risk for Trump, administration officials argued that rates will come down as the technology develops. They said the increased demand will build capacity in existing transmission lines and bring down costs per unit of electricity.

Data centers needed to fuel AI accounted for about 1.5% of the world’s electricity consumption last year, and those facilities’ energy consumption is predicted to more than double by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency. That increase could lead to burning more fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas, which release greenhouse gases that contribute to warming temperatures, sea level rise and extreme weather.

Will Google win the AI Race?

Youtube • 20VC with Harry Stebbings • November 24, 2025

AI•Tech•AI Platforms•Incumbents Vs Startups•AI Race

Overview

The content centers on the question of whether a large incumbent technology company can “win” the current artificial intelligence race.

It implicitly contrasts the strengths of established players—such as massive distribution, data, and infrastructure—with the speed and focus of newer, AI-native competitors.

The video positions the AI race not as a single, clear-cut competition but as a multi-front battle across research, products, monetization, and developer ecosystems.

Incumbent Advantages in the AI Race

Large incumbents benefit from:

Existing user bases numbering in the billions.

Deep integration into daily workflows (search, email, documents, cloud).

Vast datasets and powerful computing infrastructure.

These advantages make it easier for an incumbent to:

Rapidly ship AI features to an enormous audience.

Bundle AI into existing products, increasing stickiness.

Cross-subsidize AI investments with profits from other units.

The framing suggests that “winning” might be less about pure research innovation and more about the ability to operationalize AI at scale.

Challenges for Big Tech in “Winning” AI

Incumbents face structural and cultural constraints:

Legacy products and internal politics can slow radical change.

Risk aversion, regulatory scrutiny, and brand concerns may limit aggressive experimentation.

Speed and focus are highlighted as key advantages of smaller or more AI-native companies, which:

Can iterate on models and products without being tied to legacy systems.

Are often willing to take product and UX risks incumbents shy away from.

The implication is that even with resources, an incumbent’s ability to move quickly enough is not guaranteed.

Defining What It Means to “Win”

The discussion implies that “winning the AI race” is multi-dimensional:

Research and model performance leadership.

Product adoption and user engagement.

Revenue and margin capture from AI features and platforms.

Control of key distribution layers (search, app stores, cloud, productivity suites).

Different players may dominate different layers:

One company might lead on foundational models.

Another might own the primary consumer interface.

Yet another might monetize best through enterprise and cloud.

Implications for Startups, Investors, and Users

For startups:

There is still meaningful room to innovate on specialized products, vertical AI tools, and new interfaces.

Competing directly with incumbents at the infrastructure or general-purpose model layer is difficult, but niches, workflows, and UX layers remain open.

For investors:

The outcome of the AI race will be shaped by how much value accrues to infrastructure vs. applications.

Incumbent strength does not preclude breakout startups, particularly where incumbents are slow or constrained.

For users:

The competition should accelerate feature development and lower costs.

The trade-off may be greater concentration of power and data in a small set of companies, raising questions about privacy, openness, and long-term innovation incentives.

Key Takeaways

The AI race is not a zero-sum sprint with a single clear winner but an ongoing competition across infrastructure, products, and ecosystems.

Large incumbents hold immense structural advantages in distribution, data, and compute, giving them a strong position to capture value.

However, organizational inertia, regulation, and slower iteration cycles leave gaps for focused, AI-native players to build differentiated products.

The most likely scenario is a hybrid outcome in which incumbents dominate broad platforms while startups win in focused verticals and new interfaces.

Base44’s Founder, Maor Shlomo on Why Vibe Coding Has No Defensibility

Youtube • 20VC with Harry Stebbings • November 24, 2025

AI•Tech•Developer Tools•AI Dev Tools•Product Moats

Overview

The conversation centers on the current wave of “vibe coding” and AI-native developer tools, and why these products are structurally hard to defend as long-term businesses. The guest argues that models are rapidly commoditizing, user interfaces are easy to copy, and what looks magical in demos often collapses when exposed to real production workflows. Instead of chasing the latest UX pattern around AI-assisted coding, the real opportunity lies in deeply understanding developer pain, integrating with existing systems, and building proprietary data and workflows that can’t be easily replicated.

Why “Vibe Coding” Lacks Defensibility

“Vibe coding” refers to AI tools that let developers describe functionality in natural language and get back code or prototypes—essentially coding by “vibe” instead of explicit instructions.

The core critique is that these products mostly sit as thin wrappers around broadly available foundation models. When every competitor can access similar models via APIs, any apparent edge in code generation quality quickly erodes.

Front-end UX innovations—chat-like interfaces, canvas-based coding, or smart autocomplete—are considered shallow moats. Competitors can recreate them within weeks once a pattern is validated by the market.

Because they abstract away complexity, vibe coding tools also struggle with power users: senior engineers often prefer precise control, reproducibility, and direct interaction with code and tooling, which generic natural-language interfaces rarely support well.

Structural Challenges in AI Developer Tools

The discussion stresses that developer tools must integrate cleanly into existing workflows—IDEs, CI/CD pipelines, version control, and testing frameworks. Standalone “magic” apps that live outside this ecosystem tend to be adopted for demos and side projects, but not for mission-critical work.

Reliability, debuggability, and auditability are recurring weak points. If an AI-generated code block fails in production, teams need to understand why, how to fix it, and how to prevent regressions; most vibe coding products don’t offer that level of transparency.

Data and feedback loops are highlighted as the real differentiators: tools that capture rich telemetry about how code is used, tested, and deployed can iteratively improve suggestions in context, while generic products stay stuck at demo-level intelligence.

There is also tension between speed and correctness. Products optimized for fast “wow moments” in onboarding often pay for that later with subtle bugs that undermine trust.

Where Durable Value Can Be Built

Instead of betting everything on UI novelty, the conversation points to deep verticalization and workflow ownership as the path to defensibility.

Examples include focusing on specific languages, frameworks, or industries where one can encode domain knowledge into the product—compliance-heavy sectors, data infrastructure, or complex backend systems where correctness is critical.

Strong moats come from:

Proprietary datasets derived from real-world usage and codebases

Tight integration with core systems (repositories, build systems, monitoring)

Opinionated workflows that become the “operating system” for a team’s development process

Over time, tools that understand an organization’s architecture, style, and constraints can move beyond autocomplete and become orchestration layers for changes, migrations, and large-scale refactors.

Implications for Founders and Investors

Founders are encouraged to be skeptical of purely horizontal, model-wrapping products whose primary selling point is “we help you code faster with AI.” Those are likely to face brutal competition and price pressure.

The more promising strategy is to anchor around painful, expensive, and recurring engineering problems—like legacy modernization, infra complexity, or security—and embed AI as a means to that end, not the product itself.

For investors, the key signals of defensibility are: depth of workflow integration, stickiness with teams, data network effects, and the ability to expand from a wedge use case into a broader platform.

The conversation concludes that while vibe coding may remain a useful feature category, the enduring companies will be those that own the “boring,” infrastructure-heavy parts of software development, building compound advantages over time rather than chasing short-lived UX trends.

ChatGPT 5.1 Codex Max

Thezvi • November 25, 2025

AI•Tech•GPT

Overview and Core Claims

The piece argues that GPT-5.1-Codex-Max is a substantial but not transformational step forward in AI coding, cybersecurity capability, and agentic performance. It frames the model as OpenAI’s “real” frontier system for software engineering—faster, more capable, more persistent on long tasks, and able to operate over very long contexts—while stressing that it also inches us further along worrying trajectories in cybersecurity and AI self-improvement. The author emphasizes both the impressive quantitative gains and the ambiguities in OpenAI’s safety evaluations and external audits.

Capabilities, Benchmarks, and the METR Graph

GPT-5.1-Codex-Max is presented as OpenAI’s best coding model, with strong scores on major benchmarks: 77.9% on SWE-bench-verified, 79.9% on SWE-Lancer-IC SWE, and 58.1% on Terminal-Bench 2.0, all well above GPT-5.1-Codex.

On METR’s “automated software engineer” evaluation—the famous AI 2027 capabilities graph—the model reaches 2 hours 42 minutes (Prinz’s 50% accuracy metric), about 25 minutes longer than GPT‑5. This puts it between the previous trend lines and closer to a slower, more linear-looking trajectory.

Commentators like Daniel Kokotajlo interpret this as evidence that capability growth is currently somewhat slower than the AI 2027 fast-takeoff scenario, with timelines now “around 2030, lots of uncertainty though.” The author stresses that while the model is the new high point, it does not yet imply imminent runaway self-improvement.

System Card: Automated Software Engineer and Long-Context Compaction

OpenAI explicitly describes the goal as an “automated software engineer.” GPT-5.1-Codex-Max is trained on agentic tasks spanning software engineering, math, research, medicine, and computer use.

A key novelty is “compaction”: the model is natively trained to operate coherently across multiple context windows, allowing it to work over millions of tokens in a single task. This makes it better suited for long-running, multi-step engineering projects.

Training data includes real-world tasks such as pull-request creation, code review, frontend work, and Q&A—exactly the kind of bottlenecks that matter in modern software development.

Safety, Sandboxing, and Network Access

Basic safety metrics (e.g., disallowed content, image input, jailbreak resistance) are generally optimal or improved relative to GPT-5.1, with the notable exception of mental health responses, which remain weak—though the author notes Codex-Max is unlikely to be deployed in high-stakes mental health contexts.

Codex-Max runs inside an isolated machine in the cloud. On macOS and Linux, sandboxing is default; on Windows, there is an experimental native sandbox or Linux-based sandboxing via WSL. Users can selectively approve unsandboxed commands.

Network access is disabled by default but can be selectively enabled with allowlists and denylists. The article warns that many users are likely to “blindly or mostly blindly” approve commands and domains, despite risks like prompt injection, credential leakage, and licensing issues.

Mitigations, Preparedness, and Bio/Chem Risk

For harmful tasks (notably malware), OpenAI uses synthetic data to train the model to refuse such requests, reporting a 100% refusal rate on their Malware Requests benchmark. The author criticizes this as an inadequate metric if it doesn’t actually prevent efficient malware creation.

Similarly, GPT-5.1-Codex-Max scores a suspicious “perfect” result on prompt-injection benchmarks, which the author finds implausible given the broader consensus that prompt injection is unsolved.

Under OpenAI’s Preparedness Framework, what matters is whether the model crosses High or Critical thresholds for various risks. Biological and chemical risk were already at High, with some capability improvements but not enough to classify as Critical.

Miles Brundage criticizes system cards that only report results under refusal-heavy modes; he calls for reporting “helpful-only” performance to track real underlying capabilities. The author senses the cards are rushed and incomplete but still more informative than Google’s for Gemini 3, which he accuses of hiding key results.

Cybersecurity: Internal vs External Evals

Cybersecurity is a central domain for Codex-Max, and internal OpenAI tests show large gains:

Capture the Flag: 50% → 76% (vs GPT-5-Codex)

CVE-Bench: 53% → 80%

Cyber Range: major improvement, though the hardest scenario remains unsolved.

In one Cyber Range scenario, the model passed by exploiting an unintended misconfiguration rather than the intended attack path; the author argues this is not less scary and should count fully as capability.

These results (76%, 80%, 7/8) either demand raising concern level to High or, if High is not triggered, indicate that the tests are now too easy. OpenAI’s Safety Advisory Committee recommends increasing difficulty but still does not classify the model as High in cyber capability.

External evaluations by Irregular paint a different picture: moderate capability overall, similar or slightly lower than GPT‑5, with success rates of 37% (Network Attack Simulation), 41% (Vulnerability Discovery and Exploitation), and 43% (Evasion). GPT-5 outperforms on the hardest challenges. Irregular concludes Codex-Max would provide only limited assistance to moderately skilled attackers and could not automate end-to-end operations against well-defended targets.

The author finds the divergence between internal “big improvement” results and external “no progress or slight regression” both unexplained and concerning, suggesting a lack of curiosity from OpenAI about what’s going on.

AI Self-Improvement and Automation of AI R&D

Codex-Max advances on a suite of real-world AI-R&D-related benchmarks:

SWE-Lancer Diamond: 67% → 80%.

Paperbench-10: 24% (GPT-5) → 34% (GPT-5.1) → 40% (Codex-Max).

MLE-Bench-30: 8% → 12% → 17%.

OpenAI PRs: 45% → 53%.

OpenAI Proof Q&A: 2% (GPT-5) → 8% (Codex-Max), a jump commentators consider especially notable.

These tasks represent “real world bottlenecks” that can delay major projects by at least a day, so even modest percentage gains matter. Seán Ó hÉigeartaigh highlights the Proof Q&A jump as a strong signal of more to come.

METR judges that enabling rogue AI replication or substantial AI R&D automation within six months would require a significant break in current capability trends. Apollo Research’s evaluations find no new evidence of deception, sandbagging, or scheming likely to cause catastrophic harm.

The author uses the “boiling frog” metaphor: each incremental improvement seems acceptable in isolation, but collectively they move us closer to qualitatively different regimes of capability and risk.

Reception and Comparative Perspective

There has been surprisingly little organic reaction to Codex-Max, which the author attributes to “update fatigue” and the simultaneous hype around models like Gemini 3 and Claude Opus 4.5.

His own reaction thread finds some people enthusiastic and others unimpressed; early gestalt: Codex-Max is a solid, modest upgrade, likely outshone in some respects by Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 (though the magnitude of that upgrade is still being sorted out).

Overall, the conclusion is that GPT-5.1-Codex-Max is a meaningfully improved automated coding and R&D assistant, a new high point on critical capability graphs, and a modest but real step towards AI systems that can accelerate their own improvement—while leaving important safety, transparency, and evaluation questions unresolved.

New AI model enhances diagnosis of rare diseases

Ft • November 24, 2025

AI•Tech•Genomics•Rare Diseases•Healthcare AI

Overview

A new artificial intelligence system called PopEVE has been developed to improve diagnosis of rare diseases by more accurately predicting which genetic variants are harmful. It focuses on interpreting “missense” mutations — single-letter changes in DNA that alter amino acids in proteins — a major source of uncertainty in genetic testing. By outperforming existing tools, including Google DeepMind’s AlphaMissense, PopEVE aims to reduce the number of “variants of unknown significance” that leave patients and clinicians without clear answers.

How PopEVE Works

PopEVE analyses large populations of genomic data and patterns of natural variation to determine which changes in protein sequences are likely to disrupt function.

It applies probabilistic and evolutionary modeling to compare observed variants in humans with expected neutral variation, flagging deviations that suggest pathogenicity.

The system is designed to scale across the genome, covering millions of potential missense variants rather than only a curated subset.

By learning from real-world human diversity, it can better distinguish benign, commonly occurring variants from rare, potentially disease-causing ones.

Performance and Comparison with Existing Models

PopEVE was benchmarked against leading predictive models, including AlphaMissense, on standardized datasets of variants whose clinical impact is already known.

Across multiple metrics of accuracy and reliability, PopEVE outperformed rivals, making more correct calls about whether a variant is damaging or benign.

The improvement is particularly notable in edge cases where existing tools disagree or show low confidence, areas that are frequent pain points in rare disease diagnosis.

Its performance gains translate into a higher proportion of variants being classified with high confidence, reducing ambiguity in clinical reports.

Implications for Rare Disease Diagnosis

For patients undergoing genetic testing, PopEVE can:

Increase the chance that a previously uncertain variant is correctly labeled as disease-causing, enabling a firm diagnosis.

Help reclassify some variants as benign, preventing unnecessary anxiety, follow-up tests, or inappropriate treatments.

Clinicians and genetic counselors gain a stronger evidence base to explain findings, choose follow-up investigations, and guide family screening.

For extremely rare conditions with only a handful of known cases, better variant interpretation helps connect patients with relevant disease communities and research.

Broader Impact on Genomic Medicine and Research

More accurate variant prediction accelerates the discovery of gene–disease relationships, supporting research into novel therapies and drug targets.

Diagnostic laboratories can integrate PopEVE into their pipelines to prioritize variants for manual review, making expert curation more efficient.

Health systems may see reduced diagnostic odysseys, lowering costs associated with years of inconclusive tests and specialist referrals.

As population-level genomic data grows, PopEVE’s approach illustrates how generative and predictive AI models can turn statistical patterns of human diversity into clinically actionable insights.

Key Takeaways

PopEVE provides a step-change in interpreting missense variants, a central bottleneck in genetic diagnostics.

By outperforming models such as AlphaMissense, it demonstrates the value of combining evolutionary theory with large-scale human population data.

Its deployment could shorten time to diagnosis, clarify previously uncertain results, and support more precise, data-driven care for patients with rare diseases.

With new Opus 4.5 model, Anthropic’s Claude could remain the best AI coding tool

Fastcompany • November 24, 2025

AI•Tech•Anthropic•Coding•LLMs

Anthropic launched its newest model, Claude Opus 4.5, putting the company back atop the benchmark rankings for AI software coding.

Opus 4.5 scores over 80% on the widely-used SWE-bench, which tests models for software engineering skill. Google’s impressive Gemini 3 Pro, launched last week, briefly held the top score with 76.2%.

Anthropic’s Claude product lead Scott White tells Fast Company that the model has also scored higher than any human on the engineering take-home assignment the company gives to engineering job candidates.

Of course Opus 4.5 does a lot more than coding. Anthropic says Opus 4.5 is also the “best model in the world” for powering AI agents and for operating a computer, and that it’s meaningfully better than other models at tasks like deep research and working with slides and spreadsheets.

Opus 4.5 also notched state-of-the-art (best) scores in several other key benchmarks, including Agentic coding SWE-bench Verified, Agentic tool use T-2 bench, and Novel problem solving ARC-AGI-2.

A major challenge with applying AI in real-world work settings is the model’s ability to deal with complexity and ambiguity. White says Anthropic customers feel that Opus 4.5 is better than earlier models at dealing with uncertainty and handling trade-offs without a lot of hand-holding from human workers.

Enterprise customers are increasingly using Anthropic models for office task automation, financial modeling, and document creation, White says. Customer Fundamental Research Labs reported 20% accuracy improvements and 15% efficiency gains on Excel automation tasks using the new model, he adds.

Anthropic has been on a sprint for the past couple of months, releasing Claude Sonnet 4.5, Haiku 4.5, and new products including Claude Skills, Claude Code on the web, and industry-specific versions for financial services and life sciences.

Opus 4.5 will become the new default model for subscribers of higher-end plans, and available as a drop-down menu option for Pro, Standard, Team, and Enterprise users. It’s also available to developer customers via the company’s API, as well as via the Amazon Bedrock, Google Vertex, and Microsoft Azure clouds.

Anthropic says it’s also extending access to a beta version of the Claude plugin for Chrome, which has been in limited preview, to all Mac users. The company is also making Claude for Excel available to Mac Team and Enterprise users in beta, expanding beyond its previous invite-only research preview.

ChatGPT’s voice mode is no longer a separate interface

Techcrunch • November 25, 2025

AI•Tech•ChatGPT•VoiceInterface•UserExperience

Overview

The article explains that ChatGPT’s voice capabilities are now integrated into the same interface as text, rather than being a separate “voice mode.”

Users can speak, type, and see responses—including visuals—on a single screen, with everything updating in real time.

This change is presented as a step toward more natural, fluid interactions that resemble human conversation rather than discrete question-and-answer turns.

Unified Voice-and-Text Experience

Instead of switching into a distinct voice-only environment, users can now:

Start a conversation by voice and continue it by typing.

Type a prompt and then follow up verbally without changing modes.

Watch as responses appear on screen while also being spoken aloud.

Real-time visuals and text appear as the assistant answers, so the user can both hear and see information, which is especially useful for:

Explanatory diagrams or layout-based content.

Step-by-step instructions where users want to skim the text while listening.

Multitasking situations where glancing at the screen complements audio.

Improved Naturalness and Flow

The unified interface aims to make conversation feel less like operating a tool and more like talking to a person.

By removing the barrier between “voice mode” and “chat mode,” interactions can:

Shift seamlessly between speaking and typing based on user preference or context.

Maintain continuity; the same conversation history supports both modalities.

Enable quick clarifications and follow-up questions without mode confusion.

Real-time responses—both audio and on-screen—reduce perceived lag and keep the conversational flow smoother, which can:

Help users stay engaged and avoid losing their train of thought.

Make complex exchanges (e.g., multi-step reasoning or creative collaboration) feel more dynamic.

Use Cases and Practical Implications

Everyday productivity:

Users can dictate ideas, then refine them via typing as they see text appear.

It becomes easier to draft emails, outlines, or notes while moving between hands-free speech and precise text edits.

Learning and explanation:

Spoken explanations combined with live-rendered text and visuals can support different learning styles.

Users can pause, scroll, and re-read parts of a spoken answer without needing to replay audio.

Accessibility and convenience:

People who find typing difficult gain a more capable voice experience while still benefiting from on-screen feedback.

Those in quiet environments can switch to text easily, without leaving a separate voice interface.

Broader Significance

The integration suggests a strategic shift toward multimodal AI interactions as the default, not an optional add-on.

It positions ChatGPT as a more continuous assistant that adapts to user context in real time, rather than requiring users to adapt to rigid modes.

By making voice and text co-equal within the same screen, the change hints at future interfaces where:

Multiple modalities (voice, text, images, and possibly video) are blended transparently.

Users expect consistent memory, context, and functionality regardless of how they communicate with the system.

Overall, the article frames the update as a usability and experience improvement that could influence how people think about using AI tools in everyday life, making them feel more like conversational partners than discrete apps with separate features.

OpenAI needs to raise at least $207bn by 2030 so it can continue to lose money, HSBC estimates

Ft • November 25, 2025

AI•Funding•OpenAI•HSBC Estimate•AI Economics

Overview and Central Argument

The article examines the immense funding requirements facing OpenAI as it scales its artificial intelligence ambitions, highlighting an estimate from HSBC that the company will need to raise at least $207bn by 2030 to sustain operations while continuing to lose money. This projection underscores the capital-intensive nature of frontier AI development, where training increasingly large models, acquiring specialized hardware, and building data-center capacity demand investment on an unprecedented scale. The piece frames OpenAI as emblematic of a broader “burning platform” dynamic in artificial intelligence: delay or underinvestment could mean falling behind in a winner-takes-most race, yet the path to durable, profitable business models remains uncertain.

Capital Requirements and Business Model Pressures

The HSBC estimate reflects cumulative capital needs, not just short-term fundraising rounds, implying a continuous reliance on external investors and strategic partners.

Such large-scale funding is required to pay for high-end chips, cloud infrastructure, and energy-intensive training runs that are necessary to maintain leadership in generative AI.

The article suggests OpenAI’s current revenue model—largely based on selling API access and enterprise tools built on its models—may not yet be sufficient to cover escalating operational costs.

This creates a tension: to justify massive ongoing funding, OpenAI must demonstrate credible long-term monetization, even as it continues to operate at a loss in the medium term.

Role of Strategic Partners and Investors

OpenAI’s dependence on large strategic partners, particularly big cloud providers and major tech firms, is presented as both a strength and a vulnerability.

These partners can supply capital, cloud capacity, and distribution channels, but their own strategic interests may not always align perfectly with OpenAI’s independence or open research mission.

The article raises the prospect that future funding—given its scale—will likely come with even tighter integration into big tech ecosystems, potentially blurring the line between OpenAI and its largest backers.

Market Dynamics and Competitive Landscape

The projected funding needs are interpreted as a signal of how expensive it is to stay at the technological frontier relative to both established tech giants and well-funded start-ups.

Rival models from companies with in-house cloud and chip capabilities may enjoy structural cost advantages, increasing pressure on OpenAI to secure preferential access to compute and energy.

The article implies that the AI industry may be consolidating around a small number of extremely capital-rich players, raising questions about competition, innovation, and barriers to entry for smaller firms.

Implications for Regulation, Risk, and Society

The enormous sums involved amplify concerns about systemic risk: if AI development becomes dependent on a handful of highly leveraged projects, failures or missteps could have wide economic repercussions.

Policymakers may face pressure to scrutinize the financing structures, data practices, and safety commitments of companies that must constantly raise tens or hundreds of billions to stay competitive.

The article hints at a broader societal question: whether it is sustainable or desirable for key AI capabilities to depend on such concentrated, high-stakes capital flows, particularly when long-term benefits and risks remain uncertain.

Broader Takeaways

OpenAI’s need to raise around $207bn by 2030 crystallizes the reality that leading-edge AI is no longer a typical tech start-up game, but a capital infrastructure bet akin to large-scale energy or telecom projects.

This funding challenge will likely shape the company’s strategic decisions, partnerships, and product roadmap, influencing how quickly AI tools reach consumers and enterprises—and under what terms.

The article ultimately portrays OpenAI as standing at the center of a high-risk, high-reward contest where financial engineering, corporate alliances, and regulatory responses will be as decisive as raw technical breakthroughs.

Leonardo Unveils AI-Driven System to Defend Cities From Attack

Bloomberg • Alberto Brambilla • November 27, 2025

AI•Tech•DefenseTechnology•MichelangeloDome•EuropeanSecurity

Leonardo SpA unveiled an integrated defense system that uses artificial intelligence to neutralize a range of threats, from hypersonic weapons to drone swarms and naval attacks, in a bid to strengthen its role in European multi-domain security.

The system, dubbed Michelangelo Dome, aims to coordinate warfare platforms from below sea level to out in space across a single network, according to a statement Thursday from the state-controlled Italian company.

Nvidia Earnings; Power, Scarcity, and Marginal Costs; OpenAI Hand-wringing

Stratechery • Ben Thompson • November 24, 2025

AI•Tech•Nvidia•AIBubble•OpenAI

Nvidia earnings are the wrong place to look for evidence of an AI bubble; the company’s margins should be safe if power is the limiting factor.

Nvidia Earnings

From the Wall Street Journal, on Wednesday evening:

Nvidia reported record sales and strong guidance Wednesday, helping soothe jitters about an artificial intelligence bubble that have reverberated in markets for the last week. Sales in the October quarter hit a record $57 billion as demand for the company’s advanced AI data center chips continued to surge, up 62% from the year-earlier quarter and exceeding consensus estimates from analysts polled by FactSet. The company increased its guidance for the current quarter, estimating that sales will reach $65 billion—analysts had predicted revenue of $62.1 billion for the quarter. Shares in the world’s most-valuable publicly listed company rose about 5% in premarket trading Thursday…

Wednesday’s result will allow investors to breathe a sigh of relief. Each Nvidia quarterly earnings report has come to be seen as a financial Super Bowl of sorts as the AI boom has taken off. The company is regarded as a bellwether for both the health of the tech industry and the market as a whole. This quarter, however, the stakes seemed higher. Rarely has an earnings report from a single company been greeted with such nervous anticipation. In recent weeks, investors have sold off big tech names, worried that companies are spending far too much money on data centers, chips, and other infrastructure in the race to design and operate the world’s most powerful AI models, with little hope of recouping their investments in the near term.

Adding to the pressure is a flurry of recent AI deals structured using what critics have dubbed “circular” funding mechanisms—broadly referring to suppliers like Nvidia making large capital investments in the businesses of the customers who buy their products. Just a few months ago, investors viewed such deals with enthusiasm, pumping up shares for a variety of AI-related companies, but this week one such deal — between Nvidia, Microsoft and Anthropic — was greeted warily.

Well, the sigh of relief didn’t last long; from Bloomberg on Thursday:

A rally in Nvidia Corp. shares fizzled on Thursday after investors shrugged off a stronger-than-expected revenue forecast and assurances that the AI economy isn’t in a bubble. After initially climbing more than 5%, the stock fell 3.2% to $180.64 in New York. The broader market also declined, weighed down by AI fears and concerns over whether the Federal Reserve will cut rates in December.

It remains — as I note every Nvidia earnings — odd to look at the company’s quarterly reports as a bellwether for AI: we just came off of an earnings cycle where basically every company said they had more demand than supply, and dramatically increased their capital expenditure plans, so of course Nvidia’s earnings crushed. Where do people think all of that capital expenditure is going? More generally, when it comes to this earnings cycle there remains basically no evidence of any weakness in the AI story; overall investor nervousness seems to be entirely theoretical to date.

In this, that series of OpenAI deal announcements seems to be the driving factor in investor skittishness; X user @TMTBreakout had a good post making this point:

Stated succinctly: the “AI bubble” ascent was the paradigm that both bulls and bears were operating under for most of this year, or longer. Bad news for the AI bulls and bears: the past few weeks has brought an end to that paradigm and led us to an unexpected turning point in the dynamics of the AI trade/narrative. On the 3 year anniversary of ChatGPT’s release, no less. And we have Sam’s $1.4T 30GW splurge to thank for it. Sam’s Splurge (we’ll call it “SS”) opened up AI “pandora’s box,” shifting the AI narrative in unexpected ways…

China

China leapfrogs US in global market for ‘open’ AI models

Ft • November 25, 2025

China•Technology•OpenAI Models•US China Competition•AI Ecosystem

Beijing’s backing for “open” artificial intelligence models is rapidly shifting the balance of power in the global AI ecosystem, enabling Chinese players to gain ground in markets where US giants remain wedded to more tightly controlled, proprietary systems. The core theme is a divergence in strategy: China is encouraging the proliferation of broadly accessible, open-weight or open-source-style models, while leading American companies are prioritising vertically integrated, closed models that they own, host, and strictly license. This difference is beginning to reshape who captures global developer mindshare, how AI capabilities diffuse internationally, and which governments set key norms and standards around AI use and governance.

Open vs closed AI strategies

Chinese institutions and companies, supported by state policy and funding, are pushing AI model releases that can be downloaded, modified and deployed locally by enterprises and researchers.

By contrast, US “Big Tech” players tend to restrict their most capable models to cloud APIs, charging for access and keeping model weights proprietary.

The article frames “open” not only as a technical licensing choice but as a strategic tool in geopolitics and industrial policy, allowing China to seed global ecosystems with technology that others can build on.

Beijing’s role and motivations

Beijing views AI as a strategic industry and is deliberately cultivating an ecosystem where domestic champions can export models and tooling abroad.

Promoting more open models supports several goals: accelerating domestic innovation, reducing dependence on US technologies, and building soft power by making Chinese AI an attractive default for emerging markets.

The approach mirrors past Chinese strategies in telecoms and infrastructure: offer competitive technology with fewer usage constraints and often at lower cost to gain international adoption.

Impact on global markets and developers

In many regions, especially outside the US and EU, developers and companies are sensitive to cost, latency, data sovereignty and political constraints. Locally deployable open models can address these concerns more effectively than closed US-hosted APIs.

This creates an opening for Chinese-origin models to become embedded in foreign tech stacks, from social media tools and content platforms to enterprise software and public-sector systems.

As more developers experiment with and adapt these open models, China’s technical standards, pretrained datasets, and tooling ecosystems risk becoming de facto norms in some segments of the global market.

Implications for US companies and governance

US AI giants’ preference for closed, centralized control grants them greater ability to enforce safety protocols, manage misuse, and integrate AI deeply with their existing platforms.

However, it also leaves a gap at the “infrastructure” layer for anyone wanting autonomy over deployments, lower costs, or the ability to run models in sensitive or disconnected environments.

The divergence raises governance questions: open models can empower innovation but also make it harder to control dangerous uses, while closed models consolidate power in a few corporations and governments. The article suggests that China’s strategic bet is that the benefits of rapid diffusion and ecosystem capture outweigh these risks, and that Beijing is comfortable managing safety through other tools, including regulation and censorship at the application layer.

Broader geopolitical and economic consequences

Control of AI model ecosystems is increasingly seen as a lever of geopolitical influence, similar to dominance in operating systems, mobile platforms or telecom standards in earlier eras.

By championing open models, China can position itself as a technology provider for countries wary of US dominance or constrained by US export controls.

Over time, this could shift where value accrues in AI – from a small number of US cloud companies to a more fragmented landscape in which Chinese-origin models, tools and chips play a central role, particularly in the Global South.

Key takeaways

China is using open AI models as a strategic instrument to expand its global technological footprint.

US companies’ insistence on closed, proprietary models preserves control and monetization but risks ceding parts of the global “infrastructure AI” market.

The emerging split between open Chinese models and closed US platforms could shape not only commercial competition but also norms, standards and power dynamics in the AI era.

China Warns of Bubble Risk in Booming Humanoid Robotics Industry

Bloomberg • November 27, 2025

China•Economy•Humanoid Robots•Artificial Intelligence•Investment

China’s top economic-planning agency has warned over the risk of a bubble forming in humanoid robotics, in a rare official expression of concern about the booming sector.

“Frontier industries have long grappled with the challenge of balancing the speed of growth against the risk of bubbles – an issue now confronting the humanoid robot sector as well,” Li Chao, spokeswoman of the National Development and Reform Commission, said at a briefing in Beijing on Thursday.

More than 150 makers of humanoid robots are operating in China and their number is still rising, Li said. The country must prevent a flood of “highly similar” models from overwhelming the market and squeezing out space for research and development, she said.

The call for vigilance reflects Beijing’s unease over excess investment flooding into a sector it bills as one of the biggest catalysts for the economy in the years ahead.

Humanoid robotics is one of the six industries named by the ruling Communist Party as new economic growth drivers for the future in its guidelines for drafting China’s development plan in the five years though 2030.

Citigroup expects to see “exponential” growth in production next year from China’s humanoid robot makers. But although companies like UBTech report receiving orders worth over a billions yuan, widespread adoption of humanoid robots by households or factories has yet to materialise.