A reminder for new readers. Each week, That Was The Week, includes a collection of selected readings on critical issues in tech, startups, and venture capital. I chose the articles based on their interest to me. The selections often include viewpoints I can't entirely agree with. I include them if they provoke me to think. The articles are snippets or varying sizes depending on the length of the original. Click on the headline, contents link, or the ‘..More’ link at the bottom of each piece to go to the original. I express my point of view in the editorial and the weekly video below.

Hat Tip to this week’s creators: @stevesi, @jaredhecht, @benedictevans, @chudson, @Silva, @SylviaVarnham, @geneteare, @ZeffMax, @martin_casado

Contents

Editorial: Kids Love AI

Charles Hudson on Venture Strategies at Different Stages

Martin Casado from A16Z on OpenAI and SB 1047

Editorial: Kids Love AI

This editorial is 100% inspired by Steven Sinofsky’s essay explaining why using AI in school is not cheating.

Regular readers know I spent two weeks in Europe this summer. My two youngest sons were with me. The youngest, 17, has a medical condition that means he missed a lot of 11th grade. He had summer school and then, while on vacation, had to do two semesters of English using an accredited online course.

We were super disciplined. Daily, he did at least one module (10 questions from 200 required). At the end of each module, we fed his answers into ChatGPT and asked it to score its answer and justify its view.

He’s a good student, so ChatGPT only disagreed with a few times over 200 questions. He stuck to his answer twice and agreed with ChatGPT several times. A few times, he was right to change; a couple, he was wrong to change. Twice, they were both wrong.

His overall score of around 90% was unaffected by the collaboration. But he sat with me, reading the reasoning behind all the questions. What came out was a deeper understanding of the issues due to the reasoning articulation.

He spent a lot of time considering the reasoning before decisions were made.

It was like having the teacher sitting right there with us. When appropriately utilized, ChatGPT is an excellent, scalable virtual teacher for each child in a class.

Steven Sinofsky explains how technology is always initially considered to enable cheating before eventually, and usually quickly, becoming an accepted practice. The same is likely to happen with AI.

There is much to read in this week’s selections below pertinent to last week’s newsletter on regulation in Europe and the USA. Benedict Kelly writes about Google and search. He explains how monopolies are defeated by innovative new approaches. In the case of search, AI seems to be that innovative new thing:

… one rather deterministic lesson we might draw from all the previous waves of tech monopolies is that once a company has won, and network effects have become self-perpetuating and insurmountable, then you don’t beat that by making the same thing but slightly better, and getting a judge to give you an entry point. You win by making the old thing irrelevant.

More broadly, the EU is following one gaff with another. It has delayed its findings on Meta’s use of public posts to train AI. Why? The Information tells us:

Meta says it has been told by European regulators to delay using public posts on Facebook and Instagram to train its AI models “not because any law has been violated but because regulators haven’t agreed on how to proceed.”

And Rohan Silva in The Times weighs in:

Given the pivotal role that technology plays in driving economic growth and productivity gains, you’d assume Brussels would be pulling out all the stops to help digital businesses and close the growth gap with the US. Mais non. Europe seems hellbent on going the other way, becoming ever more statist and anti-innovation.

In light of this, I can only applaud Martin Casado of Andreessen Horowitz in this week’s ‘X of the Week.’ He publishes OpenAI’s letter to the California Government:

While we believe the federal government should lead in regulating frontier Al models to account for implications to national security and competitiveness, we recognize there is also a role for states to play. States can develop targeted Al policies to address issues like potential bias in hiring, deepfakes, and help build essential Al infrastructure, such as data centers and power plants, to drive economic growth and job creation. OpenAl is ready to engage with state lawmakers in California and elsewhere in the country who are working to craft this kind of Al-specific legislation and regulation.

He ridicules OpenAi for this openness to regulation and points out that it is self-serving.

OpenAI's letter opposing SB 1047. Wonderful to see them protect California's AI interests broadly. And doing so as an incumbent who is in position to gain from regulation at the expense of others. Thank you

My critique is that OpenAI reinforces the developments that place regulators in the role of product managers, governing what innovation is and is not permitted. There are only bad outcomes for civilization down that road. The lack of faith in science and scientists and the belief that we can trust regulators more represent an abandonment of reason. And worse, it delays innovation pending regulatory approval, as Meta’s EU adventure is showing. The delay may be a long one. I side with Steven Sinofsky, Martin Casado, and Rohan Silva.

Essays of the Week

Using AI for School is NOT Cheating

The use of AI is causing some in universities to freak out. I would worry more about NOT using AI, if history is any indication.

AUG 22, 2024

In the latest call to act on the challenges and problems with AI in this story in The Atlantic, the author posits universities and colleges do not have a plan to deal with all the fraud created by students using generative AI:

But his vision must overcome a stark reality on college campuses. The first year of AI college ended in ruin, as students tested the technology’s limits and faculty were caught off guard. Cheating was widespread. Tools for identifying computer-written essays proved insufficient to the task. Academic-integrity boards realized they couldn’t fairly adjudicate uncertain cases: Students who used AI for legitimate reasons, or even just consulted grammar-checking software, were being labeled as cheats. So faculty asked their students not to use AI, or at least to say so when they did, and hoped that might be enough. It wasn’t.

While the story shows some professors who are using AI or trying to, by and large the issue is about “fraud” with students. Putting aside the obvious irony/craziness of faculty worried about student fraud in an era of widespread faculty fraud all the way to the level of university president, the issue is not new. Whether it was calculators, encyclopedias, “online databases”, or the internet itself the idea of new technologies being labeled as cheating or fraud is not new.

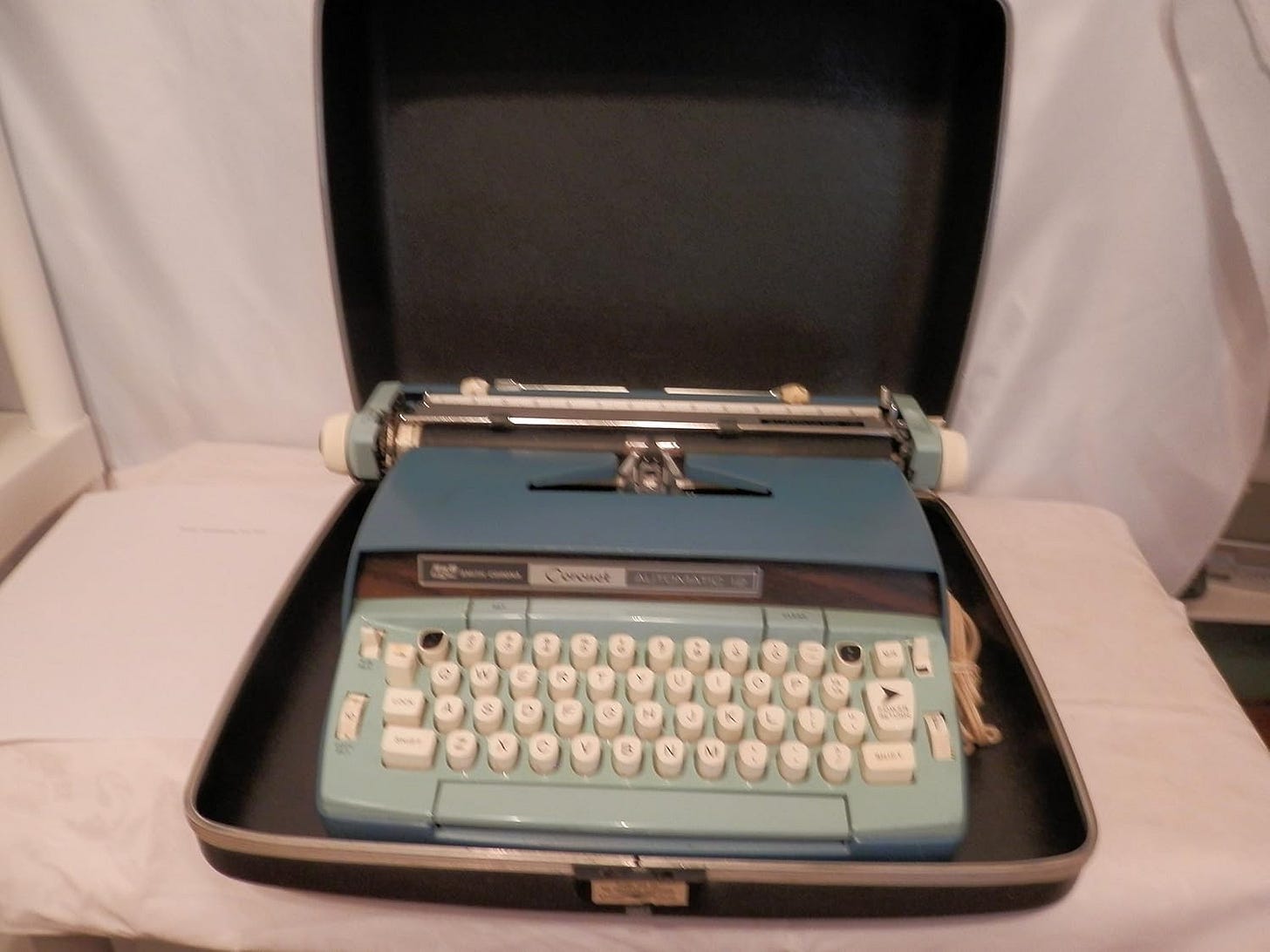

This is a personal story of getting caught on the cusp of technology change and concerns over fairness and cheating. It is about the first use of “word processors” in freshman English in 1983. This originally appeared on X.

When I was a college freshman in 1983 the DOS PC was exactly 2 years old. Cumulative to date IBM PC sales had just surpassed Apple ][ sales, with about 1.5 million units worldwide. The most common graduation gift my classmates had received was a Smith-Corona typewriter followed by a fancy TI calculator. During registration we received a punch card with our random 4-character USER ID (mine was TGUJ for use on the mainframe CORNELLA) along with a $100 credit for CPU time and disk space. As I described in "Hardcore Software" my father (for reasons I will never know) bought an Osborne computer for his business in 1981. For college I was sent off with a second one just to fix bugs in the inventory management program I wrote in dBase. No one else in my dorm had a computer.

A surprising thing happened during course registration which was a sampling of students were picked to be part of an "experiment" to take place in the required freshman writing course. Some students were told they could optionally join a class that would be using a "word processor" to write their papers. The goal was to evaluate whether students wrote better or worse if they used a word processor. Supposedly professors were tracking or measuring quality of rough drafts and final papers or something.

I was randomly chosen for the "word processor" cohort. We went to a special orientation to see the Xerox word processors and had to shell out $10 to buy an 8" floppy. The word processors were dedicated to word processing (computers that only ran one program for word processing) and there were 4 in a tiny room in the basement with one printer. I had a moment of panic because I had simply assumed I would use WordStar on my Osborne and my dot matrix MX-80 printer. I was all set up in my dorm ready to go. The professor told me I had to go to the dean to get permission to use my Osborne. It might break the experiment.

These “word processors” were ridiculous. They were up a giant hill (like all computing resources), weird, and slow. Plus 8” floppy. The keyboards had all sorts of weird colored function keys that made no sense. WordStar was already native to me and my computer was in my dorm. I knew all the shortcuts.

The dean and I had an interesting (and very short) conversation. First I was just terrified. I was 3 days into orientation and already meeting the dean. I was told I had to be in the word processor cohort because otherwise it would be "unfair" to other students in the typewriter cohorts. BUT he insisted I use a “letter quality” printer. In a panic I called home. We did not have one and was worried about the expense. I found a daisy wheel typewriter available from 47th St photo (they had a toll-free number to call to talk to a sales person and figure this all out) which I could order and get shipped to college. It connected to an Osborne over a parallel cable and I could hack WordStar to output to it and even got Bold working.

The writing class was fine. Every week we had a paper due. I was just a normal freshman up late on Thursday finishing it. I’d hit save to my 5 1/4” 90K floppy and then ^KP to print. Like a Gatling gun or teletype (think opening scene of All The President's Men) my typewriter would spew out my 5 page paper and annoy my roommate and guys across the hall.

I have no idea how the “experiment” went for our class or what conclusions they drew about using a word processor.

As it turns out, the results of the experiment wouldn’t matter at all. A funny thing happened over the traditionally long winter break in January 1984. The then #2 computer company ran a commercial on the Super Bowl about why 1984 would not be like 1984.

Uber Appreciation

Jared Hecht

August 22, 2024

Earlier this week, I hopped in an Uber with my family to get to our Lisbon apartment rental, and I felt a profound appreciation for the company. We were in a foreign country, and with the tap of a button, I could summon a car to safely get us home. It was reliable and worked the exact same way it does when I’m home in NYC or traveling anywhere else for that matter.

What Uber has accomplished over the past 15 years is nothing short of miraculous. I remember sitting outside TechCrunch Disrupt in San Francisco in 2010 when Travis pulled out his phone and showed Steve and me (and anyone else in a 2-mile radius who would pay attention) how he was calling a black car to pick him up. The app was clunky and the wait time was something like 20 minutes for a ride. Today I wait less than five minutes for a ride that is cheaper and safer than a taxi and available to me through the same app in virtually every city in the world. I don't think I've witnessed another company do anything like that in my career.

The media did an exceptional job vilifying Uber during its rise, and as a result, its history is often associated with scandal. That’s a shame because there are many important and positive things to learn from the company. Three of them are presently top of mind as I reflect on it:

Super outcomes require superhuman effort. Emil Michael, Uber’s chief business officer, has been a long-time friend of mine and was an advisor to both my companies. I watched him as he helped to build Uber from a company that had recently achieved product-market fit to a global behemoth. I’ve founded two companies and I’ve never worked as hard as he did when he built Uber. Absolute commitment to winning was part of the culture of the company. As my family was safely being transported around a foreign city earlier this week, all I could think was that wouldn’t have been possible were it not for the Uber teams’ maniacal work ethic. I remember it being commonplace to vilify the company and its leadership for its intense work culture. It would have never worked without it.

Another underappreciated aspect of Uber was its bold and innovative “capital as a moat” strategy, rapidly raising billions of dollars round after round. They were criticized for their lack of profitability and for using equity capital to block their competitors from markets and investor pools. They were deemed a capital-inefficient business that was never going to work. But they took that capital and built out physical infrastructure across the world in one decade in a way that had never been done before and at a speed that, in retrospect, seems unfathomable. Now it’s a $150B market cap and cash flow positive company that pioneered a bold and counterintuitive capital raising model currently employed by everyone involved in another transformative category, the LLM wars.

Think for yourself, and don't get swooped up by media narratives. Uber caught an infinite amount of flack as it was coming up. It was as if the world, particularly the media, was rooting for its downfall. During the moment, its hard-charging culture and agglomerate-all-the-cash strategy seemed like a recipe for disaster. At least that’s what the public narrative portrayed. But look at it now. It is almost certain that the global infrastructure Uber has built over the past 15 years would not exist were it not for the things that most people once lambasted about the company.

Competing in search

Benedict Evans

A quarter century after ‘don't be evil’ a judge has found that Google is abusing its monopoly in search. But no-one knows what happens next, and whether this ruling will change anything. Will Apple build a search engine? Will ChatGPT change search? Does it matter?

A search engine is a vast mechanical Turk - a reinforcement learning engine that uses human activity to understand the web. PageRank used signal from links created by people, but once people started using Google at scale, that usage itself created far more signal: which results you clicked on, how you changed your searches to get better results, and what else you searched for before and after. That then applies on the advertising side as well: the more search ads Google serves, the more it knows about which ads are effective and the higher its revenue-per-query.

So, search is a virtuous circle. Everyone uses Google because it has the best results, and it has the best results because everyone uses it, and hence it has the money to invest in getting even better results. That is compounded by the scale of the infrastructure needed to index and analyse the entire web (Apple estimated $6bn a year for it to match Google on top of its existing search and indexing spending), which largely precludes venture-backed startups from entering the market, but even if you had that capital, you wouldn’t have Google’s query volume and so you wouldn’t have Google’s quality. In tech this is called a network effect; in competition theory it’s called a natural monopoly.

Hence, Bing. Satya Nadella claimed that Microsoft has invested $100bn in search to date, yet Bing has only 5% of US search traffic, and both its results and its revenue-per-query are worse. It’s stuck on the wrong side of that virtuous circle.

However, there's another virtuous circle: everyone uses Google because it's the default, it's the default because it’s the best and because Google pays other tech companies billions of dollars a year in revenue shares as ‘traffic acquisition costs’ (TAC) to make it the default, and it’s the best and Google has those billions to pay because everyone uses it. In 2022, Google paid Apple about $20bn (about 17.5% of Apple’s operating income, and a 36% revenue share) and other companies $10bn to make it the default, which was close to 20% of Google’s search advertising revenue. And this was the center of the US competition case that was decided this week.

We all knew this in theory (after all, the TAC is right there in the accounts), but this week’s judgement made it a lot more tangible. 50% of search in the USA happens on channels where Google has a contract to make it the default: 28% on Apple devices, 19.4% on Android (the OEMs and telcos decide the default on Android, not Google) and 2.3% on other browsers (i.e. Mozilla) - and then another 20% happens in user-downloaded Chrome on PCs. (Amusingly, the contract means that Google pays Apple even for searches done in Chrome on Apple devices.)

A16z And Founders Fund Lead The Way In Defense Venture Capital

August 20, 2024

Anduril Industries made headlines earlier this month when it raised another $1.5 billion — matching its own record for the largest defense tech round ever and catapulting total funding numbers to likely new highs.

The massive round — co-led by Founders Fund and Sands Capital Ventures— showed the growing interest in the space by investors. That was not always the case in the venture world for reasons ranging from cultural to political.

However, in the past several years a handful of big-named firms like Andreessen Horowitz and General Catalyst have placed a significant amount of bets in the space as the venture capital world has grown and some norms have changed.

Who’s investing?

Venture funding for defense tech startups is ready to set new records. After Anduril’s huge round, so far in 2024 defense tech startups have raised $2.5 billion — per Crunchbase data — nearly matching the record high of $2.6 billion set in 2022. Last year, such startups collected only $2.1 billion total.

Helping the industry hit those new heights are the aforementioned Founders Fund and Andreessen Horowitz.

Those firms have made the most investments this year — three apiece — of any VC firm and Andreessen the most since 2021 with 14 deals. Earlier this year, Andreessen — an investor in Anduril’s previous rounds — led a $175 million Series B for autonomous surface vessels maker Saronic at a $1 billion valuation.

Not far behind is 8VC

with a dozen investments since 2021 — although only one this year, participating in the big Saronic round. Alumni Ventureshas done 11 deals in that time, including co-leading a $12 million seed round for Picogrid, which has developed a platform to allow users to control unmanned systems.

The only other firm to have double-digit investments in the defense tech space may not be known to everyone in the venture world, as Dallas, Texas-based Silent Ventures has made 10 deals since 2021 in the sector. However, that’s because the firm specializes in aerospace, defense and national security companies.

Big money

Both Founders Fund and General Catalyst come in next on the list, making eight defense tech deals apiece since 2021. They also both rank high when it comes to leading or co-leading those rounds based on the highest dollar amounts.

The Anduril deal obviously puts Founders Fund and Sands Capital in the lead this year since it was a $1.5 billion deal.

General Catalyst led the next biggest round of the year for Helsing, which develops artificial intelligence software for defense — worth approximately $489 million that values the company at $5.4 billion.

Andreessen is the only firm to lead or co-lead two rounds in the defense sector this year and the only other firm to lead or co-lead rounds totaling more than $100 million. Along with the round for Saronic, it also co-led a $7 million funding for ZeroMark, which creates auto-targeting fire control systems.

Why now?

The big money is somewhat new for defense tech.

Video of the Week

Charles Hudson on VC Strategies

AI of the Week

We can’t let EU’s anti-AI rules drag us down too

Hastily drafted in response to ChatGPT, these curbs will stunt tech in its infancy — and have a harmful effect here

Rohan Silva

Monday August 19 2024, 5.00pm BST, The Times

The investor Warren Buffett once likened compound interest to a snowball rolling down a hill, increasing in mass and speed as it tumbles on. Buffett might be the greatest financier, but that analogy feels subprime to me. A ball hurtling down a snowy ravine moves quickly, while the huge power of compounding numbers is the opposite: it’s slow, accretive, cumulative.

Look at the economic growth rates of America and the eurozone since the 2008 financial crisis. On the face of it, the annual percentage difference of 2 to 3 per cent hardly seems alarming. But annual compounding produces a profoundly divergent outcome. In 2008, the US and Eurozone economies were roughly the same size. Today, America’s is nearly twice as large. That’s why a recent report by the European Centre for International Political Economy found that every American state apart from Idaho and Mississippi now has a higher GDP per person than the EU average — and France’s income per head is now lower than Arkansas, America’s 48th poorest state.

Given the pivotal role that technology plays in driving economic growth and productivity gains, you’d assume Brussels would be pulling out all the stops to help digital businesses and close the growth gap with the US. Mais non. Europe seems hellbent on going the other way, becoming ever more statist and anti-innovation.

Eurosceptics might say it’s long been like this. In 2005 the Franco-German response to Google — a company that emerged from the effervescent entrepreneurialism of Stanford University and Silicon Valley — was to spend hundreds of millions of euros trying to build a government-owned search engine called Quaero. If you don’t believe me, just google it. (There’s no point quaeroing it — the state-run grand projet soon crashed and burnt.)

Then in 2018 Brussels launched its wretched GDPR legislation, ostensibly to protect “digital privacy” but in practice creating major obstacles for small companies to scale because of onerous requirements around storing and processing data within Europe.

As with most flawed regulations, this red tape disproportionately affected startups, while large businesses could more easily absorb the costs of compliance. Indeed, five years on from GDPR, if you look at the 50 global startups worth $10 billion or more, only one is based in the EU while 30 are American.

Sadly, in the face of overwhelming evidence that their top-down approach has failed, EU leaders haven’t tried a different tack, such as market-oriented reforms to reduce barriers for digital businesses. Instead in 2022, Brussels introduced the draconian Digital Market Act, which has clobbered tech companies with fines worth tens of billions of euros.

But the pièce de résistance is the EU’s AI Act, hastily drafted and passed this year in response to the public debate sparked by the launch of ChatGPT. Breathlessly heralded by European leaders as “the world’s first AI legislation”, it’s genuinely hard to overstate how dreadful for innovation and growth these rules will be. For starters, the legislation thickheadedly clamps down on AI models in general (which can be used in all kinds of ways), rather than more sensibly focusing on potentially harmful specific applications of AI, such as deep-fake pornography videos.

Bizarrely, the EU has set an arbitrary upper limit on the size and power of these AI models — and in such a rapidly progressing area, that ceiling has already been exceeded by the latest AI systems, meaning these can’t be used in Europe. We’re only at the beginning of the AI age, so setting blanket limits like this is as barmy as a 1960s legislator setting an upper limit on the processing speed allowed in computer chips, with no way of knowing how the technology would develop in the following decades.

On top of this, the EU is introducing curbs on AI in fields like healthcare and medicine, as well as imposing onerous requirements on developers to provide users with detailed summaries of the content used to train AI models. EU officials admit the red tape burden will be significant for small firms, easily adding up to six-figure amounts for startups. No wonder the EU bureaucrat chiefly responsible for the AI Act has confessed to Bloomberg: “The regulatory bar maybe has been set too high… There may be companies in Europe that could just say there isn’t enough legal certainty in the AI Act to proceed.”

The rushed rules are so patchy and the AI field so fast moving, it’s thought a further 60 pieces of secondary legislation will be needed to plug the gaps. This will have a chilling effect on AI innovation. Indeed, Apple has already announced that these regulations mean it can’t offer new AI features to EU customers, while Meta has pulled the plug on launching its latest AI model in the EU, blaming the “unpredictable” behaviour of regulators there.

That’s a shame for European consumers but the bigger issue is that while global tech corporations can spend the money needed to create a separate dumbed-down version of their software for the EU market, many smaller companies will be forced to avoid the EU altogether.

CEOs of Meta, Spotify Argue EU Regulation Hampering Open-Source AI

Source:The Information

Meta says it has been told by European regulators to delay using public posts on Facebook and Instagram to train its AI models “not because any law has been violated but because regulators haven’t agreed on how to proceed.”

The comments were made in an Economist opinion piece Wednesday written jointly by CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, who cited the directive as evidence of how Europe’s “fragmented regulatory structure” was hampering the growth of open-source AI in the region.

Meta previously said it would not release future multimodal AI models in the EU because of the regulatory environment. The CEOs called on EU regulators to take a “new approach with clearer policies and more consistent enforcement.” This year, both Meta and Apple have altered plans for product releases because of the EU’s new tech rules.

News Of the Week

Lucky 13: A Baker’s Dozen Join Unicorn List In July

August 13, 2024

New unicorn counts jumped in July, as 13 companies joined The Crunchbase Unicorn Board.

Nine of the new herd came from the U.S., while two healthcare companies joined from the U.K., a green energy company from China, and a bike taxi startup from India.

Four of the new unicorns this past month were under 3 years old at the time they were valued at or above $1 billion with one — a foundation model developer for robotics — launching out of stealth.

Healthcare/biotech companies took the lead with three companies that joined the board from this sector. Other industries each counted a single newly minted unicorn in July.

Who invested?

Across this group of companies a few investors have more than one portfolio company, which is impressive given the small count. While active investors were largely Silicon Valley-based, only two of the new unicorns are headquartered in Northern California.

Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed Venture Partners and SV Angel

each invested in three portfolio companies across this batch. Sequoia invested in the most rounds with seven across its three portfolio companies.

Google Ventures, US Innovative Technology Fund, General Catalyst, Founders Fund, Caffeinated Capital and angel investor Elad Gil each have two portfolio companies across this cohort.

Here are the new unicorns in July by sector.

VR AR

Infinite Reality, a creator of 3D immersive environments, raised a $350 million funding at a $5.1 billion valuation from an undisclosed multifamily office. The 5-year-old Connecticut-based company acquired London-based LandVault, a platform creating 3D digital twins for physical environments, for $450 million.

Healthcare and biotech

Element Biosciences, a DNA sequencing biotech company enabling genetic analysis, raised a $277 million Series D led by Wellington Management. The 7-year-old San Diego-based company was valued at $1 billion. Its customers include academia, biotech, cancer research and agriculture according to the announcement.

London-based Flo Health, a women’s health app, raised a $201 million Series C led by General Atlantic. The 8-year-old company was valued at $1 billion. Flo has 70 million monthly active users and 5 million paid subscribers.

London-based Huma, a remote patient-monitoring healthcare service, raised an $80 million Series D. It launched the Huma Cloud Platform, with regulatory approval to allow other services to provide digital monitoring and data collection. The 13-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

Robotics

Skild AI, came out of stealth with a foundation model for robotics. It closed on a $300 million Series A led by Bezos Expeditions, Coatue, Lightspeed Venture Partners andSoftBank. Investors participating include Felicis

, Sequoia Capital, Menlo Ventures, General Catalyst, CRV, SV Angel, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Amazon Industrial Innovation Fund and the Amazon Alexa Fund. The Pittsburgh-based company is a year old and was valued at $1.5 billion.

Professional Services

AI native legal tech service Harvey raised a $100 million Series C led by Google Ventures. The 2-year-old San Francisco-based company was valued at $1.5 billion. The company has raised seed through Series C funding in under two years with seed through Series B led by the OpenAI Startup Fund, Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins, respectively.

Energy

China-based LONGi Hydrogen Energy, a green hydrogen company, raised a $138 million Series A funding. The 3-year-old company was valued at $1.4 billion.

Privacy and security

Seattle-based Chainguard, a provider of security for open source software, raised a $140 million Series C led by Redpoint, Lightspeed Venture Partners and IVP. The 2-year-old company was valued at $1.1 billion. The seed, Series A and Series B were led by Amplify Partners, Sequoia Capital and Spark Capital.

Media

Cosm, an event venue entertainment company based in Los Angeles, raised $250 million from private equity and family offices. The 4-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

Logistics

Supply chain management company Altana raised a $200 million Series C led by US Innovative Technology Fund. Its customers are governments and enterprises required to keep up to date with trade restrictions and enable procurement. The New York-based 5-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

Fintech

Burlingame, California-based Aven, a credit card that provides rates tied to home equity lines of credit, raised a $142 million Series D led by General Catalyst and Khosla Ventures. The 5-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

Defense tech

Saronic, a defense technology company that builds unmanned surface vehicles for maritime use, raised a $175 million series B led by Andreessen Horowitz. The Austin-based 2-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

Transportation

Bangalore-based Rapido, a bike taxi company raised a Series E of $119 million led by Westbridge Capital. The 8-year-old company was valued at $1 billion.

The Most-Active US Series A And B Investors Made More Bets In H1 2024

August 16, 2024

Andreessen Horowitz, General Catalyst and Khosla Ventures were the most-active U.S. investors leading Series A and B rounds globally in the first half of 2024. The three topped a list of 13 investors that made seven or more early-stage investments.

We found that the majority of the more active investors listed above increased their pace from a year earlier, an indication that the venture markets could be picking up.

Of the three busiest investors, Khosla Ventures picked up the pace more dramatically compared to the first half of 2023, leading Series B rounds in geologic hydrogen service Koloma, autonomous driving truck service Waabi (co-led with Uber), and radiology report writing automation startup Rad AI.

Andreessen was one of the leading investors to lead fewer Series A and Series B rounds when compared to a year earlier. However, Andreessen still tops the leaderboard this year. The firm has also been one of the more active multistage venture investors since the second half of 2022 when venture funding slowed, based on an analysis of Crunchbase data.

Led amounts

Looking at the same investors by amounts led at Series A and B, we find a big range. Arch Venture Partners, a life sciences-focused investor tops the list with $1.9 billion invested in rounds it led or co-led. Arch co-led the $1 billion funding with Foresite Capital in AI drug discovery company Xiara Therapeutics.

General Catalyst, which led rounds reaching $1 billion in the first half, co-led the round in Mistral with DST Global. It also led the Series B in Collaborative Robotics, which is building robots that work alongside humans.

Andreessen co-led the Series B in AI voice software developer ElevenLabs with angel investors Nat Friedman and Daniel Gross. The firm also led the Series A in text-to-image generative AI company Ideogram.

Healthcare and AI lead

The increase in funding at Series A and B in the U.S. in H1 2024 was concentrated in larger bets, and in two leading industries, healthcare/biotech and AI, according to an analysis of Crunchbase data.

These two industries stood out across these 125 Series A and B investments led by these active firms. AI-related companies represented 40% of companies and healthcare/biotech around 25%. Other notable sectors were financial services companies, with 13% of investments, and hardware, with around 11%.

Off peak

When we look back at the most active leads at Series A and B rounds in H1 2022, the peak for Series A and B counts led by a U.S. investor, we find a very different picture. Tiger Global led or co-led 100 rounds at this stage, while Insight Partners led 75 on a global basis. Fast-forward to H1 2024 and Tiger Global led only one round in the first half of 2024, while Insight led six at Series A and B according to rounds disclosed in Crunchbase.

Startup of the Week

Meet Black Forest Labs, the startup powering Elon Musk’s unhinged AI image generator

3:45 PM PDT • August 14, 2024

Elon Musk’s Grok released a new AI image-generation feature on Tuesday night that, just like the AI chatbot, has very few safeguards. That means you can generate fake images of Donald Trump smoking marijuana on the Joe Rogan show, for example, and upload it straight to the X platform. But it’s not really Elon Musk’s AI company powering the madness; rather, a new startup — Black Forest Labs— is the outfit behind the controversial feature.

The collaboration between the two was revealed when xAI announced it is working with Black Forest Labs to power Grok’s image generator using its FLUX.1 model. An AI image and video startup that launched on August 1, Black Forest Labs appears to sympathize with Musk’s vision for Grok as an “anti-woke chatbot,” without the strict guardrails found in OpenAI’s Dall-E or Google’s Imagen. The social media site is already flooded with outrageous images from the new feature.

Black Forest Labs is based in Germany and recently came out of stealth with $31 million in seed funding, led by Andreessen Horowitz, according to a press release. Other notable investors include Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan and former Oculus CEO Brendan Iribe. The startup’s co-founders, Robin Rombach, Patrick Esser, and Andreas Blattmann, were formerly researchers who helped create Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion models.

According to Artificial Analysis, Black Forest Lab’s FLUX.1 models surpass Midjourney’s and OpenAI’s AI image generators in terms of quality, at least as ranked by users in their image arena.

The startup says it is “making our models available to a wide audience,” with open source AI image-generation models on Hugging Face and GitHub. The company says it plans to create a text-to-video model soon, as well.

Black Forest Labs did not immediately respond to TechCrunch’s request for comment.