A reminder for new readers. Each week, That Was The Week includes a collection of selected readings on critical issues in tech, startups, and venture capital. I chose the articles based on their interest to me. The selections often include viewpoints I can't entirely agree with. I include them if they provoke me to think. The articles are snippets or varying sizes depending on the length of the original. Click on the headline, contents link, or the ‘More’ link at the bottom of each piece to go to the original. I express my point of view in the editorial and the weekly video below.

Hat Tip to this week’s creators: @DarioAmodei, @2020science, @rex_woodbury, @ttunguz, @steph_palazzolo, @rocketalignment, Matthew B. Crawford , @alex, @jasonlk, @michael_bodley, @AndreRetterath, @mwseibel, @cademetz, @mikeisaac, @eringriffith, @mgsiegler, @DanMilmo,

Contents

Editorial: AI: Where to Invest?

Machines of Loving Grace - Dario Amodei

Is this how AI will transform the world over the next decade? - Andrew Maynard

The Second $100B AI Company - Rex Woodbury

The Premise of a New S-Curve in AI - Tomaz Tunguz

78 Artificial Intelligence Startups That Could Be for Sale This Year

Netflix's insane cash generation - Alex Wilhelm

The Number of Active VCs is Down 62% From Its Peak. And Down Again in 2024. Jason Lemkin

VCs are rewriting the opportunity fund playbook—or scrapping it entirely Michael Bodley

Why Should VCs Become More Data-Driven? - Andre Reterath

When did AI Get This Good?

Andrew Keen and Simon Johnson (2024 Nobel Prize Winner)

Squarespace

Michael Seibel on Consumer AI

Editorial: AI. Where to Invest?

This week I was a guest on Brent Leary and Paul Greenberg’s CRM Playaz.

The topic was ‘AI's impact on Enterprise Apps Angel and Seed Investing.’

You should click through to hear the discussion but here is a snippet from X.

This week’s essays focus a lot on the same questions. Dario Amodei writes an essay called ‘Machines of Loving Grace’, and there are responses. Rex Woodbury makes a strong case for consumer applications. Sequoia Capital shows a graphic with a big blank space - leaving the question unanswered: Sequoia Capital’s ‘Generative AI’s Act o1

But Sequoia does state:

We are seeing a new cohort of these agentic applications emerge across all sectors of the knowledge economy. Here are some examples.

Harvey: AI lawyer

Glean: AI work assistant

Factory: AI software engineer

Abridge: AI medical scribe

XBOW: AI pentester

Sierra: AI customer support agent

By bringing the marginal cost of delivering these services down—in line with the plummeting cost of inference—these agentic applications are expanding and creating new markets.

In this context, having started as being sure AI would not destroy cloud companies it stated:

That being said, we are no longer so sure. See above re: cognitive architectures. There’s an enormous amount of engineering required to turn the raw capabilities of a model into a compelling, reliable, end-to-end business solution. What if we’re just dramatically underestimating what it means to be “AI native”?

My own view is that AI is not a layered architecture at scale. That does not mean there will not be applications or services for both consumers and work. But it does mean that the default is that AI use cases at the customer or consumer layer are likely to be features not businesses.

A feature can survive for quite a while, and even get traction like NotebookLM from Google (see this week’s Video of the Week). But it is most likely going to be incorporated into the AI platforms eventually, and probably quickly.

If I am right then the current VC inclination to avoid investing (see Aileen Lee’s piece from last week) is prudent. And it may be the case that there is no compelling case to change that behavior.

Tomasz Tunguz this week talks about the next AI S Curve, but is rightly focused on the performance of ever larger models.

I am not saying that this landscape will not change. A lot depends on how aggressive OpenAI, Anthropic and others go after the use cases. But The Information’s article - 78 Artificial Intelligence Startups That Could Be for Sale This Year - suggests that the mood away from investing in late entrants or features is in full swing.

One use case I feel sure about is using AI to evaluate venture backed companies. This does not use LLMs, but rather combines heristics that are created by and score humans with Machine Learning pipelines.

Rob Hodgkinson wrote about how SignalRank’s platform combines scoring human attributes with data driven decision making. You would have received it as a cross-post on Thursday.

He explained how SignalRank captures human attributes and transforms them into predictive signals by quantitatively analyzing investor behaviors and decisions rather than focusing on company-level data or financial fundamentals. Here's how this process works:

1. Codifying Investor Behavior: SignalRank ranks investors by round stage (such as seed, Series A, Series B) and captures attributes like the number of successful unicorns they’ve backed, their efficiency in identifying unicorns (unicorns/investments ratio), and their Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC). This ranking allows SignalRank to evaluate investors' perceived quality rather than startups' quality directly.

2. Aggregating Social Sentiment: Instead of purely relying on company fundamentals, SignalRank aggregates investor patterns and decisions across multiple rounds. It considers which investors are leading specific rounds and assigns value based on these decisions, essentially converting social sentiment (investors endorsing a company by investing) into quantifiable data. For instance, a Series B led by a highly ranked investor may imply greater potential value for the company.

3. Round Scores and Patterns: By examining investments over a rolling five-year period, SignalRank identifies patterns across multiple funding rounds. Each round is converted into a "round score" and then further into a "company score," benchmarking them against similar rounds in the same funding vintage. This creates percentile scores for rounds and companies, giving an objective signal from subjective investor activities.

4. Dynamic Thresholds and Market Heat Analysis: SignalRank also uses a dynamic thresholding system to adjust how it interprets investor signals in different market conditions. For example, during a market bubble, investor behavior may reflect herd mentality rather than independent decision-making. SignalRank’s system aims to recognize such situations by using recent market data (90-day averages) to maintain rigorous investment standards.

5. Emphasis on Investor Quality Over Company Data: SignalRank believes that exceptional investor behavior reveals more about future success than current company-level data, which can be noisy or unreliable. By focusing on investors, who are playing "multiple hands across multiple tables," rather than entrepreneurs playing a "single hand," the model aims to aggregate consistent human judgment over time.

6. Combining Human and Machine Insights: SignalRank captures qualitative human attributes like investor reputation, their history of selecting winning companies, and the implicit social hierarchy of investors. These subjective factors are turned into structured data, which the SignalRank algorithm uses to create objective signals. This approach allows the model to harness top investors' intuition, experience, and networks, making it a combination of human insight and machine learning precision.

In essence, SignalRank’s method turns the socially constructed elements of venture capital—such as investor endorsement, market perception, and the quality of backers—into quantifiable metrics that can be analyzed, scored, and used for predictive outcomes. This strategy helps identify companies with a higher probability of delivering significant returns based on the historical patterns of investor involvement.

We made our 20th investment into the SignalRank Index this week. Supporting early stage investors by underwriting their pro-rata shares in Series B rounds. Qualified and Accredited investors can buy the index for $25.54 a share if they invest a minimum of $500,000.

This is the first index of private market assets available to qualified and accredited buyers. Once listed it will be available to retail buyers also where the minimum purchase will be a single share.

As money flows into the index it is used to support our partners pro-rata in the next set of companies. The goal is to have an index of around 200 companies at scale, constantly refreshed through exits and new investments.

Click through below to see how data intelligence can select top performing private companies.

Essays of the Week

Dario Amodei

Machines of Loving Grace

How AI Could Transform the World for the Better

October 2024

I think and talk a lot about the risks of powerful AI. The company I’m the CEO of, Anthropic, does a lot of research on how to reduce these risks. Because of this, people sometimes draw the conclusion that I’m a pessimist or “doomer” who thinks AI will be mostly bad or dangerous. I don’t think that at all. In fact, one of my main reasons for focusing on risks is that they’re the only thing standing between us and what I see as a fundamentally positive future. I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.

In this essay I try to sketch out what that upside might look like—what a world with powerful AI might look like if everything goes right. Of course no one can know the future with any certainty or precision, and the effects of powerful AI are likely to be even more unpredictable than past technological changes, so all of this is unavoidably going to consist of guesses. But I am aiming for at least educated and useful guesses, which capture the flavor of what will happen even if most details end up being wrong. I’m including lots of details mainly because I think a concrete vision does more to advance discussion than a highly hedged and abstract one.

First, however, I wanted to briefly explain why I and Anthropic haven’t talked that much about powerful AI’s upsides, and why we’ll probably continue, overall, to talk a lot about risks. In particular, I’ve made this choice out of a desire to:

Maximize leverage. The basic development of AI technology and many (not all) of its benefits seems inevitable (unless the risks derail everything) and is fundamentally driven by powerful market forces. On the other hand, the risks are not predetermined and our actions can greatly change their likelihood.

Avoid perception of propaganda. AI companies talking about all the amazing benefits of AI can come off like propagandists, or as if they’re attempting to distract from downsides. I also think that as a matter of principle it’s bad for your soul to spend too much of your time “talking your book”.

Avoid grandiosity. I am often turned off by the way many AI risk public figures (not to mention AI company leaders) talk about the post-AGI world, as if it’s their mission to single-handedly bring it about like a prophet leading their people to salvation. I think it’s dangerous to view companies as unilaterally shaping the world, and dangerous to view practical technological goals in essentially religious terms.

Avoid “sci-fi” baggage. Although I think most people underestimate the upside of powerful AI, the small community of people who do discuss radical AI futures often does so in an excessively “sci-fi” tone (featuring e.g. uploaded minds, space exploration, or general cyberpunk vibes). I think this causes people to take the claims less seriously, and to imbue them with a sort of unreality. To be clear, the issue isn’t whether the technologies described are possible or likely (the main essay discusses this in granular detail)—it’s more that the “vibe” connotatively smuggles in a bunch of cultural baggage and unstated assumptions about what kind of future is desirable, how various societal issues will play out, etc. The result often ends up reading like a fantasy for a narrow subculture, while being off-putting to most people.

Yet despite all of the concerns above, I really do think it’s important to discuss what a good world with powerful AI could look like, while doing our best to avoid the above pitfalls. In fact I think it is critical to have a genuinely inspiring vision of the future, and not just a plan to fight fires. Many of the implications of powerful AI are adversarial or dangerous, but at the end of it all, there has to be something we’re fighting for, some positive-sum outcome where everyone is better off, something to rally people to rise above their squabbles and confront the challenges ahead. Fear is one kind of motivator, but it’s not enough: we need hope as well.

The list of positive applications of powerful AI is extremely long (and includes robotics, manufacturing, energy, and much more), but I’m going to focus on a small number of areas that seem to me to have the greatest potential to directly improve the quality of human life. The five categories I am most excited about are:

Biology and physical health

Neuroscience and mental health

Economic development and poverty

Peace and governance

Work and meaning

My predictions are going to be radical as judged by most standards (other than sci-fi “singularity” visions2), but I mean them earnestly and sincerely. Everything I’m saying could very easily be wrong (to repeat my point from above), but I’ve at least attempted to ground my views in a semi-analytical assessment of how much progress in various fields might speed up and what that might mean in practice. I am fortunate to have professional experience in both biology and neuroscience, and I am an informed amateur in the field of economic development, but I am sure I will get plenty of things wrong. One thing writing this essay has made me realize is that it would be valuable to bring together a group of domain experts (in biology, economics, international relations, and other areas) to write a much better and more informed version of what I’ve produced here. It’s probably best to view my efforts here as a starting prompt for that group.

Is this how AI will transform the world over the next decade?

Anthropic's CEO Dario Amodei has just published a radical vision of an AI-accelerated future. It's audacious, compelling, and a must-read for anyone working at the intersection of AI and society.

ANDREW MAYNARD, OCT 13, 2024

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei’s essay “Machines of Loving Grace”1 has been causing quite a stir this past week. At over 50 pages long (yes, I printed it out), it lays out an audacious and detailed vision of how artificial intelligence could accelerate progress and transform the world for the better. It’s also one that I think anyone interested in how AI might radically transform society over the next 10 - 20 years should read.

It’s easy to dismiss articles like this from tech leaders — they have a tendency to be deeply hyperbolic and overly optimistic in their pronouncements — but Amodei’s is different. He writes with depth and clarity, and with a vision that’s tempered with humility and reason.

And while I don’t agree with everything he says, there’s enough thought and substance in his essay to warrant careful consideration. I must confess that I rather enjoyed reading the essay and found it refreshingly enlightening.

That said, this is a thought piece that I think will challenge a lot of readers, whether they are fixated on rather narrow and unimaginative applications of generative AI, or are ideologically opposed to the concept of an AI-accelerated future.

But if Amodei’s essay is approached as a conversation starter rather than a manifesto — which I think it should be — it’s hard to see how it won’t lead to clearer thinking around how we successfully navigate the coming AI transition.

Given the scope of the paper, it’s hard to write a response to it that isn’t as long or longer as the original. Because of this, I’d strongly encourage anyone who’s looking at how AI might transform society to read the original — it’s well written, and easier to navigate than its length might suggest.

That said, I did want to pull out a few things that struck me as particularly relevant and important — especially within the context of navigating advanced technology transitions.

Framing The Possibilities

Amodei’s paper starts out by asking how AI might transform the world over a 5 - 10 year period, once “powerful AI” has been achieved — a point he believes we could hit as early as 2026.

The framing is intriguing as it avoids the hype surrounding visions of AI utopias and dystopias, and instead allows plausible — but nevertheless radical — possibilities to be considered.

This does, though, depend on us achieving what he calls powerful AI first.

Here, Amodei is refreshingly specific on what “powerful AI” might look like. Avoiding speculation around artificial general intelligence, or AGI, he develops the idea of AI as a technology that is capable of problem solving with agency, and at a scale and speed that surpasses what is possible by humans.

His bar for intelligence here is machines that can “prove unsolved theorems, write extremely good novels, write difficult codebases from scratch” and more. He also acknowledges that the nature of intelligence is complex and contested, and in doing so he foreshadows some of the challenges of AI-based problem-solving within a complex human society.

Much of the essay hinges on the concept of an AI-driven “compressed 21st century” — the idea that, with AI’s help, progress could be ramped up by a factor of 10 or so beyond what humans alone are capable of.

If this were possible, he argues, the next projected 100 years of human innovation and progress could be compressed into around 10 years. It’s something that may not sound that transformative, until you begin to realize that you may see advances in your lifetime that you otherwise assumed wouldn’t occur until after you’re long gone!

If it’s assumed that this accelerated speed of innovation could occur after the emergence of powerful AI, Amodei’s ideas are compelling. But this is an assumption that’s likely to be limited by a number of factors — and Amodei tackles at least some of these head-on.

These factors include (and I’m changing his order here):

The speed the world operates at outside of a machine-based intelligence, recognizing that, in Amodei’s words, “the world only moves so fast”;

Physical laws, that ultimately rate-limit what is possible (the speed of light being one of the better known ones);

Intrinsic complexity, where even an exceptionally powerful AI is likely to run into challenges in solving complex problems;

Constraints from humans, where human behavior is an inseparable part of intrinsic complexity — unless there are fundamental changes to what it means to be human; and

The need for data, where even an exceptionally capable AI cannot solve problems by simply making stuff up.

These limiting factors are what led to Amodei restricting his compression factor to one AI year of progress being equivalent to ten human years.

In some cases I think even this is overly optimistic — especially when human behavior is thrown into the mix — but even thinking through these limiting factors is an important part of the conversation around how AI might radically compress the rate of progress.

Navigating Advanced Technology Transitions

Building on the framework he constructs, Amodei goes on to explore — in some detail — possible AI-driven advances in five areas that cover biology and physical health, neuroscience and mental health, economic development and poverty, peace and governance, and work and meaning.

In each of these sections he considers what might be plausible within a 5 - 10 year window after the emergence of powerful AI. The arguments he makes are considered and thoughtful, and accompanied by a refreshing level of humility where Amodei admits he may be wrong. But he also argues that, while the future is unknowable, it’s still important to consider plausible futures as we think about how AI may transform the world.

And in this, his thinking aligns closely with my work around navigating advanced technology transitions.

AI Eating Software

The Accel 2024 Euroscape was unveiled earlier today at SaaStock in Dublin and you can view the full presentation here.

*********************

AI - the main driver of value creation in the tech world

AI is rewriting software - literally and figuratively. The NASDAQ keeps climbing higher, up 38% in the last 12 months and beating new all time highs. Out of the $8.4T of value created in the past year, $5.3T is coming from the six tech titans that are investing tens of billions into AI: Apple, Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon and Nvidia. As AI is starting to unlock an unprecedented wave of productivity improvements across the enterprise, the development of this new tectonic shift seems unstoppable.

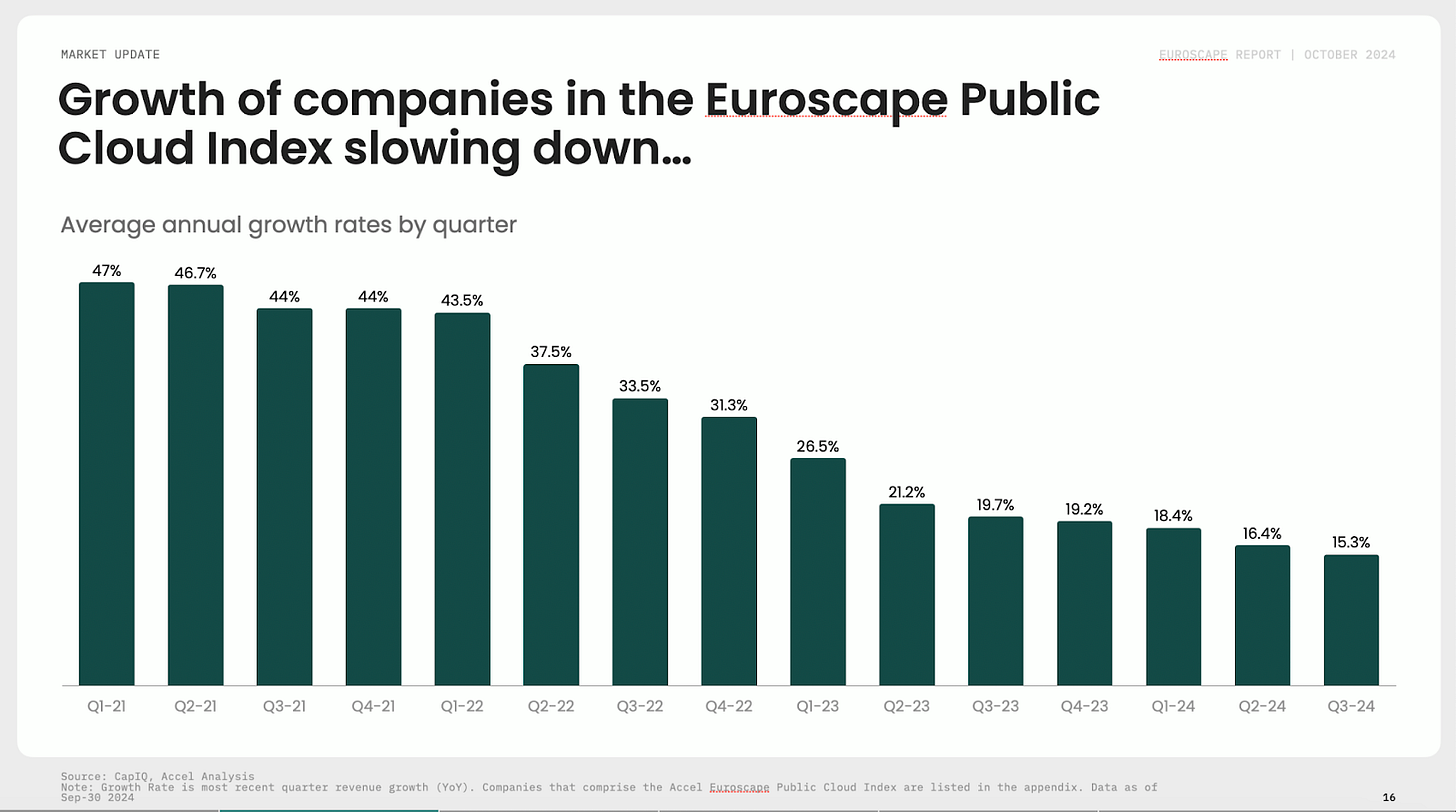

However, outside of the world of AI, the perspective isn’t as bright, with shadows of geopolitical uncertainties and the risk of recession looming.This environment combined with the digestion of 2020/21 high software spend and the shift of enterprise IT budgets to AI has been hard on both public and private cloud companies, putting huge pressure on growth. The Euroscape Index of public cloud companies has progressed at half the pace of the Nasdaq and the average growth rate shows a decline from 47% at their peak in Q2 2021 to 15% in Q3 2024. In 2021, 23 companies in the index were growing more than 40% per year compared to none today. The era of high software growth is fading away and leaves companies no other choice but to focus on profitability.

In this context, the cloud IPO market shows little signs of reopening. However, M&A activity remains solid, with 2024 already above 2023 at $58.7B. The M&A market remains driven by very large deals, with Synopsys’ acquisition of Ansys for $35B being the largest this year so far. The big tech titans are still missing in action, constrained by intense regulatory pressure and their focus on AI. The take private activity also remains healthy with 2024 on track to reach $40B, which is in line with 2023.

AI investments pushing venture funding back up

After three years of consecutive decline, funding of private AI and cloud companies across the US and Europe is climbing again at $79B, up 27% vs. 2023 and 65% vs. 2020. With AI making up $32B (40.3%) of this number and driving the majority of growth, non-AI funding is now tracking 2020’s levels at $47.3B.

When we zoom in on venture AI financing, three facts are striking:

US is leading the AI race: out of the $56B invested in 2023-24, roughly 80% has gone to US companies vs. 20% for Europe and Israel

The investments are heavily concentrated with ⅔ of the funding going to the top 6 companies in each region

⅔ of the funding has been invested in companies building foundation models

These numbers reflect the expectation of the venture community that a limited set of 12 or so companies will generate tens of billions of dollars of value in the next 5-10 years to justify these levels of investments. With OpenAI recently valued at $150B+ on the back of record breaking revenue growth, we don’t expect the flow of investments to slow down in the short term.

As billions of dollars are being put to work, the pace of development of new models is increasing, evolving from text to multi-modal, the performance of the model is increasing across all benchmarks and the cost of inference is pushed down drastically - eg. the cost of inference for 1,000 tokens on GPT4 has gone down 90% from March 2023 to May 2024. Huge progress is also coming on the text to video creation side with impressive previews from Google and Meta and Black Forest Labs (the team behind Stable Diffusion) expected to release a new video model in the coming quarters.

Game of AI thrones

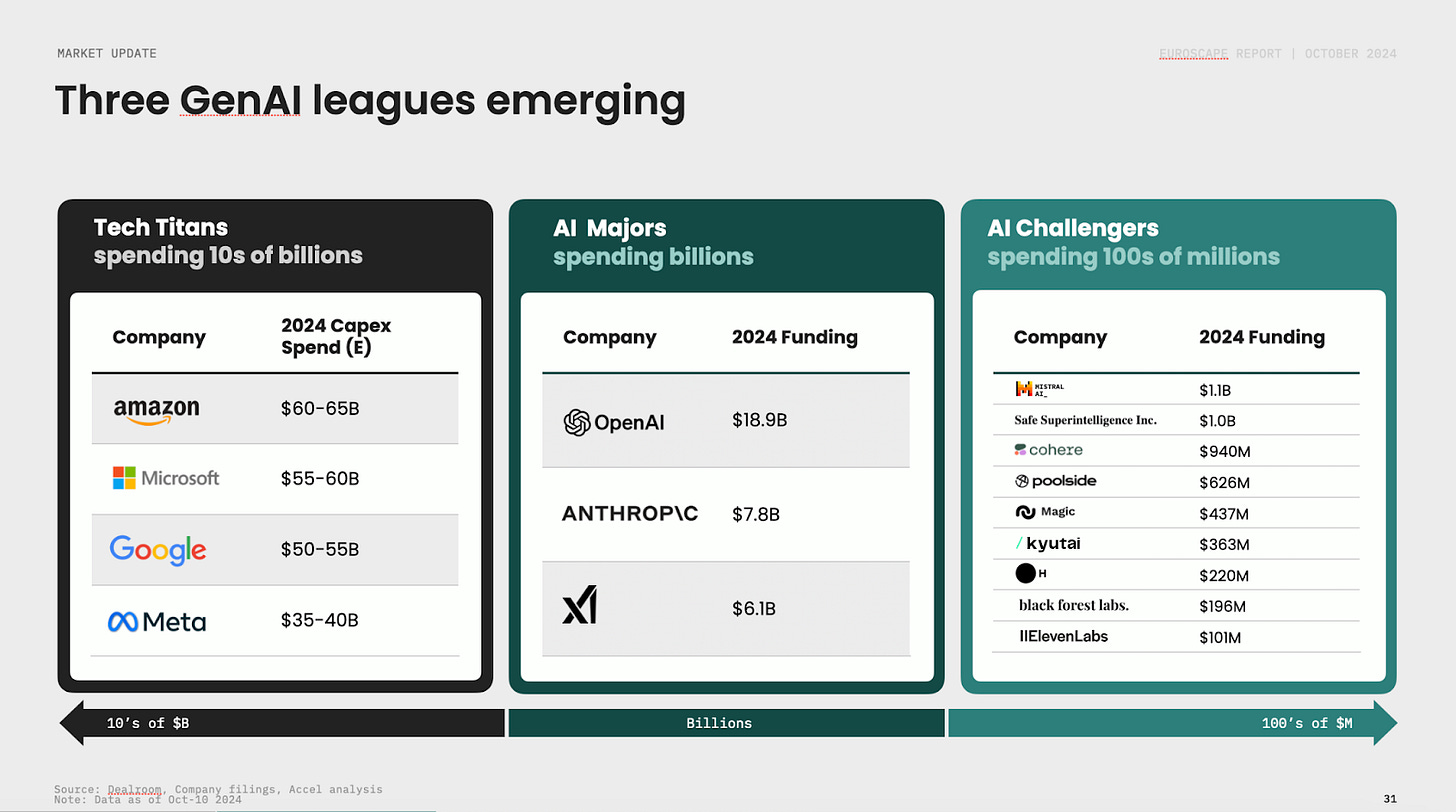

Will AI foundation models be a “winner takes all” market? Probably not. While Microsoft has a strong head start with its relationship with OpenAI, we are just in the very early innings of the race and it is too early to call it. If we look at the world today, there are three AI leagues:

The Titans: Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Meta, investing each $30-60B in AI per year, including capex

The Majors: OpenAI, Anthropic and X, each spending billions of dollars per year

The Challengers: a small number of scale ups (eg Cohere, H, Mistral,, Black Forest Labs etc…) each spending 10’s to 100’s of millions per year

It will be interesting to see in the coming months if investment capacity is the only driver of success or if more focused models and workflows can take the lion’s share of specific markets. In many applications and in particular in everything touching enterprise workflow automation, cheap inference costs and very low latency are key requirements, leading us to think that more focused models will play a significant role in the future.

The rise of Enterprise Agentic workflows

Text focused models have started to impact the productivity of enterprises primarily on the software development side, improving productivity of developers by 20%+, on the customer support side, dramatically deflecting the number of contacts managed by humans (numbers we are hearing are in the 20-40% range and increasing) and on the media creation side. Next to these use cases already in production, most large enterprises have been experimenting with internal applications and expect to deploy them next year.

We expect the next generation of models to include agents specifically trained to execute business tasks and workflow. These models will generate a new wave of automation for enterprises as AI will handle the execution of more complex tasks and tasks with a large number of possible outcomes that current automation tools are struggling to address. Initial announcements have been made by Microsoft and we expect new releases in this field next year and enterprises to start experimenting with them. One challenger to watch is H, the foundational companies focusing on agentic workflow who received investments from UiPath and is expected to release their first product in the coming months.

The top 100 2024 Accel Euroscape winners

As AI dominates the cloud world, it is not surprising to see a big shift in the list of winners this year. We’ve also adjusted the categories to reflect the new landscape of AI driven business models. You can see the full list and more in the report here

The Second $100B AI Company

The Case for Consumer AI

OCT 16, 2024

By my count, there are 31 U.S. technology companies with a market cap over $100B. Of that list, I count only one founded in the last 15 years: Uber, which trades at $178B.

If we go back a few years—further back than 2009—we get a few more: Shopify (2006), Palo Alto Networks (2005), Meta (2004), ServiceNow (2004), Tesla (2003). And if we look beyond the United States, we get companies like Pinduoduo (2015) and Meituan (2010), both Chinese.

I expect the list of $100B+ tech companies founded since 2009 to grow in the coming years: Airbnb should join the ranks ($85B today), and Crowdstrike will eventually make it ($78B today). Private companies like SpaceX and Stripe should IPO and break the barrier. And I’m sure I missed a company or two in my quick analysis.

But the point is: there are not many technology companies that make it to $100B.

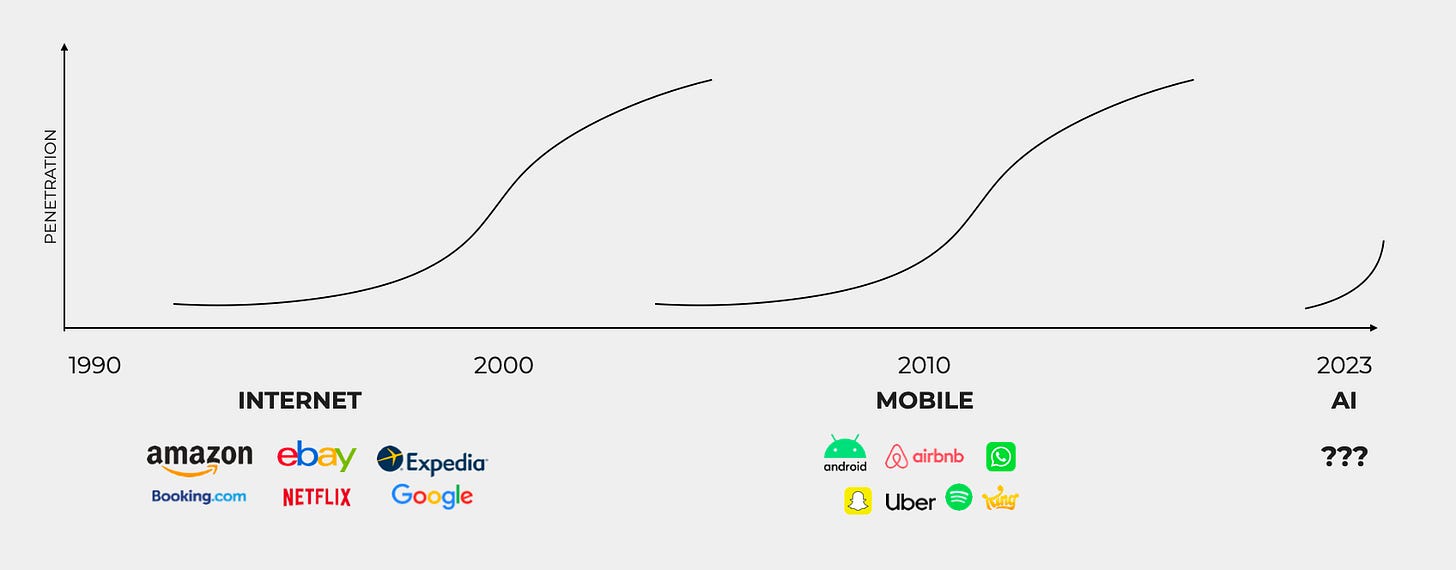

By 2034, in 10 years time, I expect we’ll have one or two AI companies join the ranks. New technology eras—internet, mobile, cloud—have traditionally propelled a couple new companies into that rarified air. The question now becomes: who’s next?

My prediction is this: the first AI company to eclipse $100B in market cap will be a consumer AI company.

This piece was initially titled, “The First $100B AI Company.” I changed the title to “The Second $100B AI Company” because we know the first: OpenAI, which just raised $6.6B at a $157B valuation (the largest venture round ever). Of course, OpenAI is both a foundation model company and an application company, a consumer company and an enterprise company. For the purposes of this piece, we’ll assume OpenAI goes public and eclipses that $100B threshold. The more interesting question becomes: what other companies will achieve the same? Which company becomes the secondcompany to hit $100B in market cap?

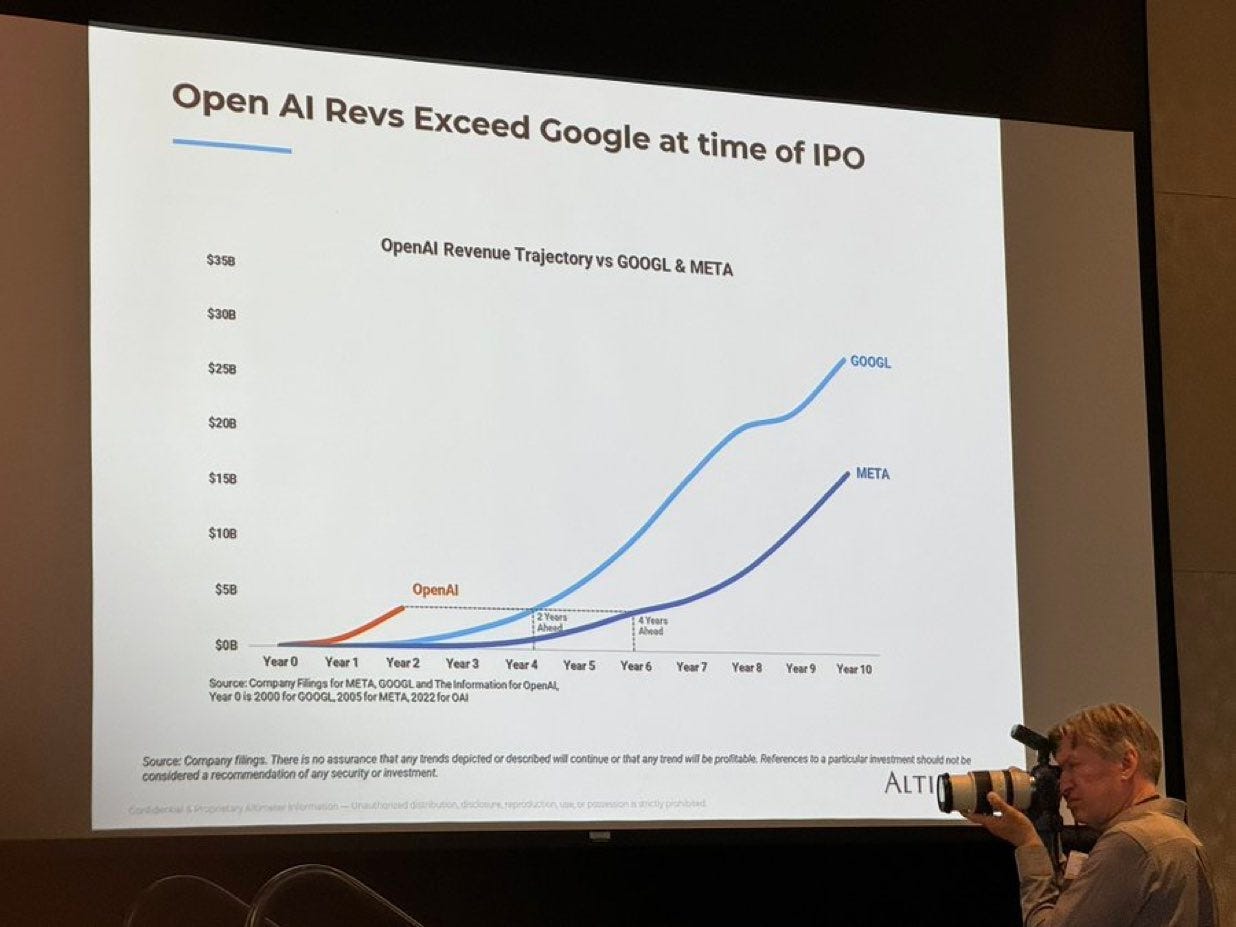

The case for OpenAI’s $157B price—a price tag that would give most investors sticker shock—is its revenue trajectory and centrality to the AI revolution. Take this chart from Altimeter’s Brad Gerstner, which positions OpenAI’s revenue growth alongside Google’s and Facebook’s:

Impressive. Not many companies can grown revenue from $3.7B to $11.6B in a year, as OpenAI expects to do next year. (The company generated $300M in revenue last month, up 1,700% since the start of the year.)

The above chart makes a compelling case for the $157B valuation. Google trades at a $2.05 trillion market cap, Meta at $1.49 trillion. It was only in 2018 that Apple became the first tech stock to eclipse the $1T barrier; today, Apple trades at $3.6T and we have six trillion-dollar tech companies. Ten years out, the list of $1T companies may double or triple, and OpenAI has a real path to that mark given its importance to both AI’s foundation model layer and application layer. The world is getting bigger, catalyzed by rapid technological innovation; in the coming decade, $1T might be the new $100B and $100B might be the new $10B.

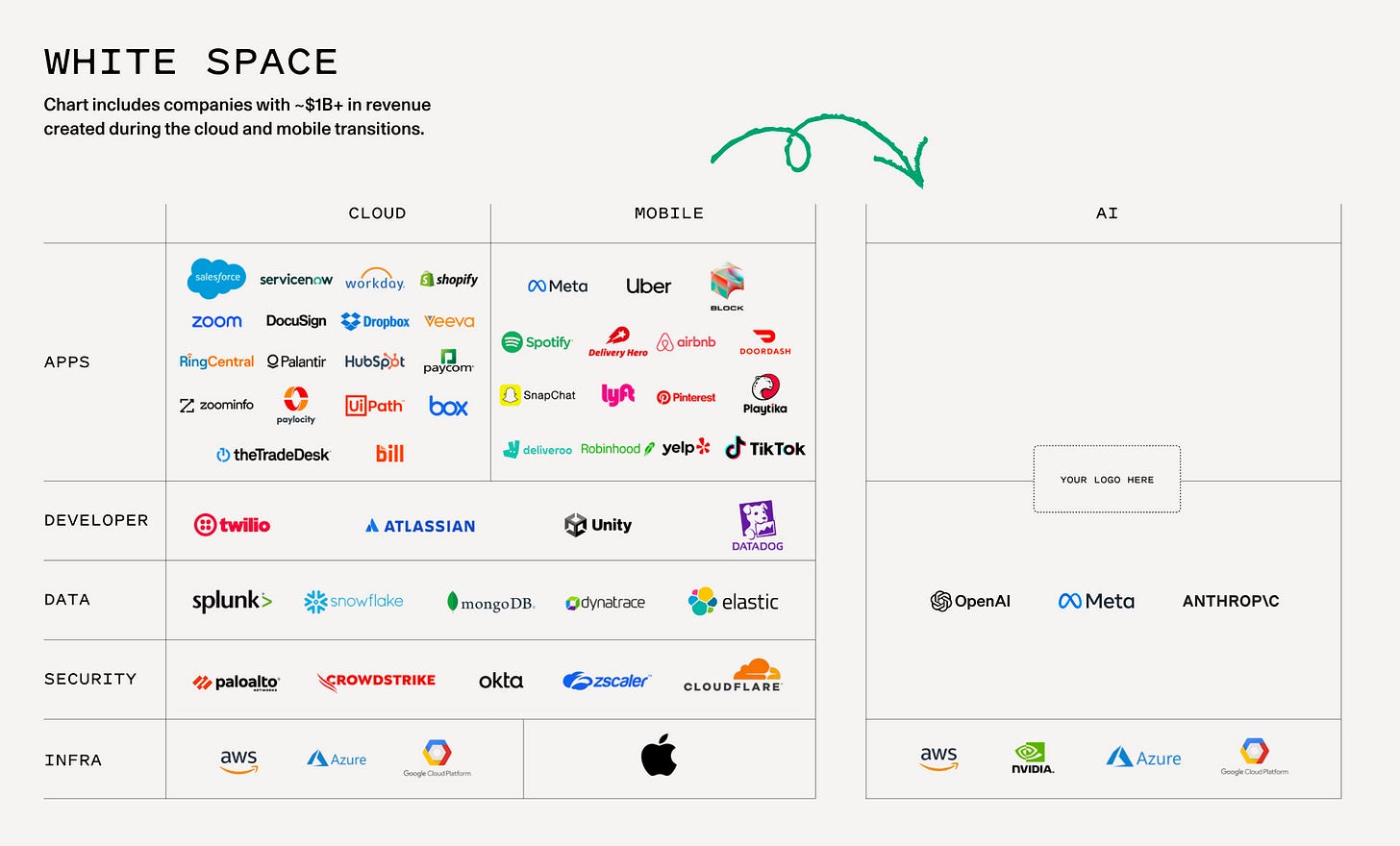

As AI’s foundation layer has crystallized, we’ve seen a few fiefdoms emerge. OpenAI is aligned with Microsoft, of course; Anthropic is partnered with Amazon / AWS; Google has DeepMind; and Meta is investing heavily into the space. The (likely) winners at this layer of the stack are set. So if the foundation layer is stabilizing, where does new value get created? The application layer, of course.

My favorite excerpt from Sequoia’s recent piece on AI was this paragraph:

Imagine you want to start a business in AI. What layer of the stack do you target? Do you want to compete on infra? Good luck beating NVIDIA and the hyperscalers. Do you want to compete on the model? Good luck beating OpenAI and Mark Zuckerberg. Do you want to compete on apps? Good luck beating corporate IT and global systems integrators. Oh. Wait. That actually sounds pretty doable!

The app layer is still early, and 2024, 2025, and 2026 should be key vintages for AI applications. (Comparing to mobile: the period of 2009 to 2013 birthed companies like Uber, Lyft, Instagram, Snap, Robinhood, and Coinbase.)

The cloud transition gave us roughly 20 companies doing over $1B in revenue; the mobile transition gave us another 20. So what will be the 20 companies borne from the AI revolution that do $1B+ in revenue?

This is an interesting framework through which to approach early-stage entrepreneurship and venture capital. Today’s an exciting moment in time: it’s not unlikely that a company that will eventually find itself in the top right of the chart above—$1B+ in revenue—is being created this very month. We may have five or six of those companies created this year.

Much of the focus on AI has been on B2B agents. In Digital Native we’ve covered how AI is eating away at services—big categories like law, insurance, banking. (See: AI Is a Services Revolution.) Services are a multi-trillion-dollar opportunity, and many of the disrupters here will be B2B. But others will be B2C, and history has shown that venture-backed B2C outcomes are often bigger. We looked through this data in June’s The Consumer Renaissance.

It’s a little bizarre that VCs are still skittish on consumer today. Again, big consumer wins are typically larger than big enterprise wins—relative to Snowflake’s market cap, Uber is ~3x in size, Airbnb is ~2x in size, and DoorDash is roughly equal. (Snowflake is the biggest enterprise IPO of the last decade.)

The Premise of a New S-Curve in AI

Since July, have you noticed how much better your AI model has become? Measuring them is hard to do. All we can do is quantify the vibe : is this one better than that one?

Elo is a score that measures how often one model wins against another, as judged by a human. Which model answers the prompt : “Describe the differences in texture between a Pink Lady and a Macoun apple” better? The one with the higher Elo score.1

In the last four months, the top 100 models have improved their Elo by about 60 points, with the top models now at 1339 vs 1287 in July.

The biggest performance gains occurred at the center part of the distribution. Researchers have driven significantly more performance with innovations in algorithms.

The smallest models have increased performance most. October models have increased their win rates by nearly a third in four months. All of the models have improved their competitive win rates by more than 20%.

In July, we posed the question : what happens when model performance asymptotes? Progress in small, medium, & large models is linear in Elo-terms.

But the mega models show more data points of inflection, suggesting the recent innovations in reasoning & scale (the biggest models have grown from 200b parameters to more than 400b) have produced the beginning of a new high-growth S-curve.

..More

78 Artificial Intelligence Startups That Could Be for Sale This Year

Developing AI models is costly and customers are not yet sold on the benefits of using AI

By Stephanie Palazzolo and Rocket Drew

Oct 17, 2024, 6:00am PDT

Reality is setting in for many artificial intelligence startups. Facing the huge costs of developing AI models and questions about when customers will see returns on their investments, some companies have found safety in the arms of larger tech firms through acquisitions or acqui-hires. Others have laid off staff or are shutting down.

Most of the startups that decided to sell, cut staff or shut down were developing their own AI models or robots, or hadn’t raised new capital in at least two years. An analysis of the 300-plus companies in The Information’s Generative AI Database identified 78 early-stage companies that fit one or both criteria—in other words, that could be targets for acquisition. See the full list here.

The Takeaway

• We identified 78 startups in our Generative AI Database that are working on costly projects or haven’t raised funds in two years

• Some companies have already been acquired, or founders have left for big tech firms

• Others have laid off staff or are shutting down

Developing large models is extremely expensive, making it difficult for model developers such as Inflection, Adept AI and Character.AI to compete with well-heeled rivals such as OpenAI and Anthropic. The founders of those firms went to work at Microsoft, Amazonand Google, respectively.

Two companies developing image generators, Ideogram and Stability AI, have held talks that could have led to the companies’ being acquired, The Information has reported. Stability later raised new funding from a group of investors led by former Facebook President Sean Parker.

While we were working on the list, four generative AI startups identified by our methodology were acquired or licensed their technology to a company that also hired much of their staff: Robust Intelligence, a maker of security software; Covariant, a developer of industrial robotics software; OctoAI, whose software makes AI models run more efficiently; and Aquarium Learning, a maker of AI tools.

Other AI developers have switched gears, focusing less on training their own models to avoid competing against the likes of OpenAI and Anthropic. German startup Aleph Alpha, for instance, is now instead developing software to help enterprises use AI tools and models, whether its own or those of other companies.

Our list does not include companies that are not likely to get acquired anytime soon, such as OpenAI, Anthropic and xAI. We’ve included other factors that could be relevant to a potential acquirer, including revenue and profit, growth, number of employees, total funds raised and whether a company has raised significant funds from a strategic investor that could become an acquirer.

Startups Up for Sale

Several startups that have engaged in deal talks or been approached by potential buyers are building tools to help developers make AI-powered applications. These are sometimes called infrastructure startups, a category that includes companies like OctoAI and synthetic data startup Tonic.AI.

Some makers of AI applications also are facing challenges, as customers have realized that they can use OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Anthropic’s Claude to complete the same tasks at lower cost.

Tome, whose software can quickly prepare presentations, has laid off employees twice this year and shifted its product focus. Copywriting platform Jasper AI last year cut its internal valuation and revenue projections. Will Dean, chief financial officer of Persado, another copywriting company, said the company is not looking to be acquired but "We're always kind of open to opportunistic corporate development opportunities." A representative of Echo AI, which uses AI to analyze customer conversations, said the company is "open to those kinds of offers."

Leaders of some startups on our list said they are not looking to be bought because their revenue is growing. Hippocratic AI is focusing on releasing its healthcare AI model, which recently started generating revenue. Luma, which uses AI to generate videos, is not interested in an acquisition and has tens of millions of dollars in annual revenue.

Other companies, including scrapbooking platform Crate and Mendel, which uses AI to analyze clinical data, said they plan to raise more money in the coming months.

Subpar VC Returns

Some of the companies that have been acquired recently have fetched a small fraction of their valuation a few years ago. Nvidia bought OctoAI last month for $165 million—a big drop from the $900 million it was last valued at in 2021, The Information reported.

Such deals are less than ideal for investors. When Microsoft agreed to hire Inflection’s founders in March, investors received 1.5 times their investment—or less. That’s a far cry from the return venture capital investors typically seek, which is at least 10 times their original investment.

But founders and investors are often forced to accept subpar prices if they don’t think a company’s revenue will catch up to its prior high valuation, said Matt Murphy, a partner at Menlo Ventures and an investor in Anthropic.

He offered this example: Investors put money into a company at a valuation of $1 billion, but the founders now think it may take five years to reach a revenue level that would justify that price. “So either way investors won’t make money, whether we sell at $200 million or $1 billion,” Murphy said. Investors may want to get a smaller amount of money sooner that they can invest in other companies.

And sometimes acquirers offer founders a deal that’s hard to resist, said Rob Toews, an investor at Radical Ventures, which has backed model developer Cohere.

Bye bye, reality.

And bye bye, republic? The military-industrial complex gets up to new tomfoolery.

OCT 18, 2024

Yesterday there was an item from The Intercept that made my eyes pop. “The Pentagon Wants to Use AI to Create Deepfake Internet Users.” The reporting is based on a procurement document of the Special Operations Command, which, in addition to taking care of jobs such as we learn about in movies and the news (killing Osama bin Laden, for example), is also deeply invested in psychological operations and propaganda in the service of whatever mission they are handed by civilian authorities.

The procurement document, which seems to be more of a “wish list” than a record of actual appropriations, states that “special operations command (SOF) are interested in technologies that can generate convincing online personas for use on social media platforms, social networking sites, and other online content.” Specifically, SOF wants to be able to create online profiles that “appear to be a unique individual that is recognizable as a human but does not exist in the real world.” The hope is to be able to generate selfie video with full backgrounds “to create a virtual environment undetectable by social media algorithms.”

All of this would be disturbing enough, if one supposed that the targets of these psy-ops would be confined to foreign actors. But it is well established that the information warfare techniques developed in the Global War on Terror were turned to domestic political purposes after the 2016 election. I am removing the paywall from an April 2023 post where I went deep into that:

So now we have the military-industrial complex seeking the capability to elide the distinction between reality and politically useful fakery. This is not comforting, given that our domestic politics (and that of the Western powers more generally) currently has as its distinguishing feature the nearly comical attempts at narrative-control of an establishment that is desperately flailing against democratic challenge. Reality is the last refuge, the real limit on power. The new technologies threaten to turn politics into epistemic warfare, all the way down.

..More

Netflix's insane cash generation

OCT 18, 2024

What I missed during Netflix’s return to form

Shares of Netflix are up over 6% in pre-market trading after the Amerian streaming giant reported earnings. As my former sister publication wrote after Netflix dropped its Q3 results:

Revenue beat Bloomberg consensus estimates of $9.78 billion to hit $9.83 billion in Q3, Netflix reported after the market close on Thursday, an increase of 15% compared to the same period last year.

Netflix expects revenue to tip over the $10 billion mark in the fourth quarter, posting growth of just under the 15% it managed in Q3.

Netflix, at this age, with its competitive load, is still growing at 15% and is profitable to boot?

That from a company that saw its growth collapse to near-zero just last year?

Impressive.

And I’m not kidding, here’s Netflix’s quarterly revenue growth (YoY) since 2023:

That Netflix has rebounded to healthy growth levels is to be applauded. And the company’s ad-support tier is growing and expected to reach “critical ad subscriber scale for advertisers in all of [its] ads countries in 2025.” Netflix did caution investors that it doesn’t “expect ads to be a primary driver of our revenue growth in 2025.” Still.

Apart from all the good news at Netflix, there’s an entirely separate story that I’ve missed: It is now a cash-generating machine:

Recall that in the 2018-2020 timeframe there was ample criticism that Netflix was spending too much, growing too little, and was in, according to a Wedbush analyst, “a vicious spiral to the bottom in content spend.”

I don’t want to dunk on critical commentary, but Netflix did prove folks wrong and is now generating mountains of cash. Hats off.

There are other companies that have shown a similar curve. Here’s Uber:

It is possible to turn a cash inferno into a cash gusher, but I wonder if we’re looking at the exceptions that prove the rule that it’s hard to do so, instead of undercutting concerns that cash burn is a risk.

The Number of Active VCs is Down 62% From Its Peak. And Down Again in 2024.

by Jason Lemkin | Blog Posts

So it’s truly strange times in Venture Capital. Boom and Quiet Bust … at the same time.

On the one hand:

AI is fueling a massive boom in venture investing, and a massive resurgence in unicorn and decacorn investing. From OpenAI to Anthropic to and more, massive amounts of venture capital are flowing into AI.

The top funds keep raising more funds, and investing in many cases quickly. The top funds are still “going back to market” and deploying quickly.

YCombinator valuations are higher than ever, and rounds are filled faster than ever. Even as they move to 4 batches a year. YCombinator is just a slice of the startup world. But it’s such a prominent one, that the fever and fervor to fund YC startups makes everything seem fast and furious.

On the other hand:

IPOs have almost ground to a halt and M&A is way, way down. More on that here.

Revenue multiples are way down, even as revenues themselves continue to grow. The average public SaaS company only trades at around 5x ARR. It’s hard for VCs to make money at those multiples. Not impossible, but hard.

All but the top VC funds are struggling to raise new funds. Instead, they are quietly hunkering down.

Net net, what’s really happening outside of Andreesen, Sequoia, and YC (and similar)? Things are way down in terms of activity is the answer.

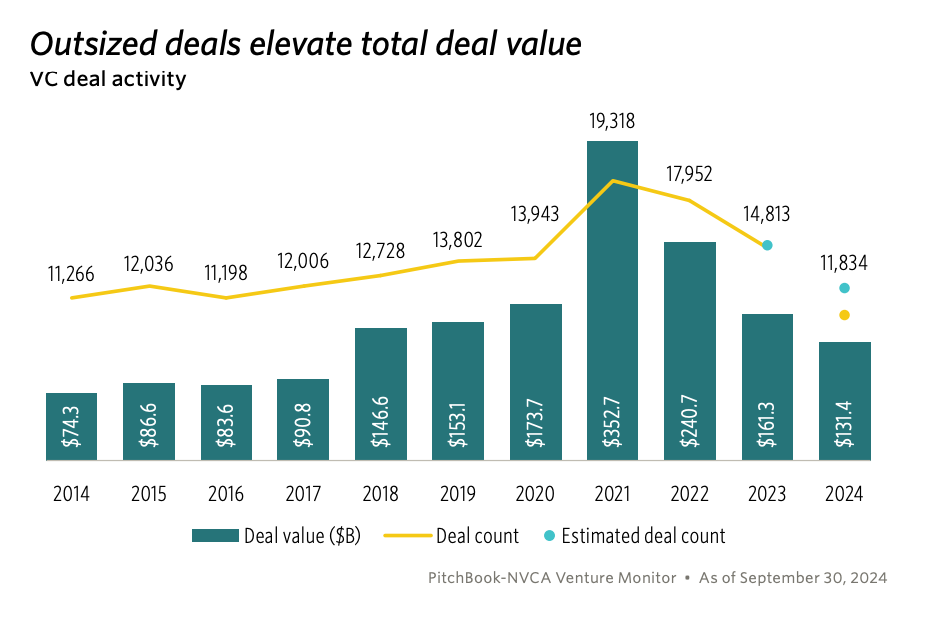

We can see it in the latest data from Pitchbook and the NVCA, which track data all across VC firms:

Even as the biggest and best funds VC invest furiously — the rest are investing less, or not at all.

You can see above the the # of VC firms investing is down ~62% from its peak of 2021, and at the moment, is pacing to be down even -25% from 2023.

This makes sense. The top VC funds can easily raise new funds, but the rest are struggling.

And Mega Deals are masking the fact that overall deals are still down, and down more in 2024:

It’s a sign of the Mixed Times today in venture. The Haves are still running a version of the 2021 playbook, just focused on AI.

And the rest? It’s kind of like 2014-2016….

VCs are rewriting the opportunity fund playbook—or scrapping it entirely

Published October 17, 2024

Demand for VC funds that double down on winning investments is shifting as investors see their best companies as overvalued, overcapitalized and without a clear path to go public.

GPs typically run opportunity funds to back standout portfolio companies as they mature. The pitch to LPs is that it increases exposure to growth-mode companies on the verge of profitability or an IPO.

With the IPO slowdown, that pitch has fallen flat. VCs have dialed back their opportunity offerings—or reoriented those strategies to go after secondary stakes in startups or other venture funds.

In extreme cases, investors are abandoning capital they’ve already raised. CRV is returning more than half its $500 million opportunity fund, the veteran tech investor said earlier this month, citing untenable startup valuations.

Part of the pushback from LPs on continuation funds stems from an “inherent conflict of interest,” said Steve Brotman, founder and managing partner of Alpha Partners.

“Many VCs raised opportunity funds not because of their skillset, but due to high LP demand,” Brotman said. “In essence, many LPs were forced into these funds by top-tier early-stage VCs who said: ‘Invest in both our early-stage and opportunity funds, or we’ll reduce your allocation in the high-performing early-stage fund.’ Now, LPs are the ones cutting back.”

Newfangled opportunity funds

The opportunity fund hasn’t been left for dead, and there are signs that VCs may be changing their definition of the term.

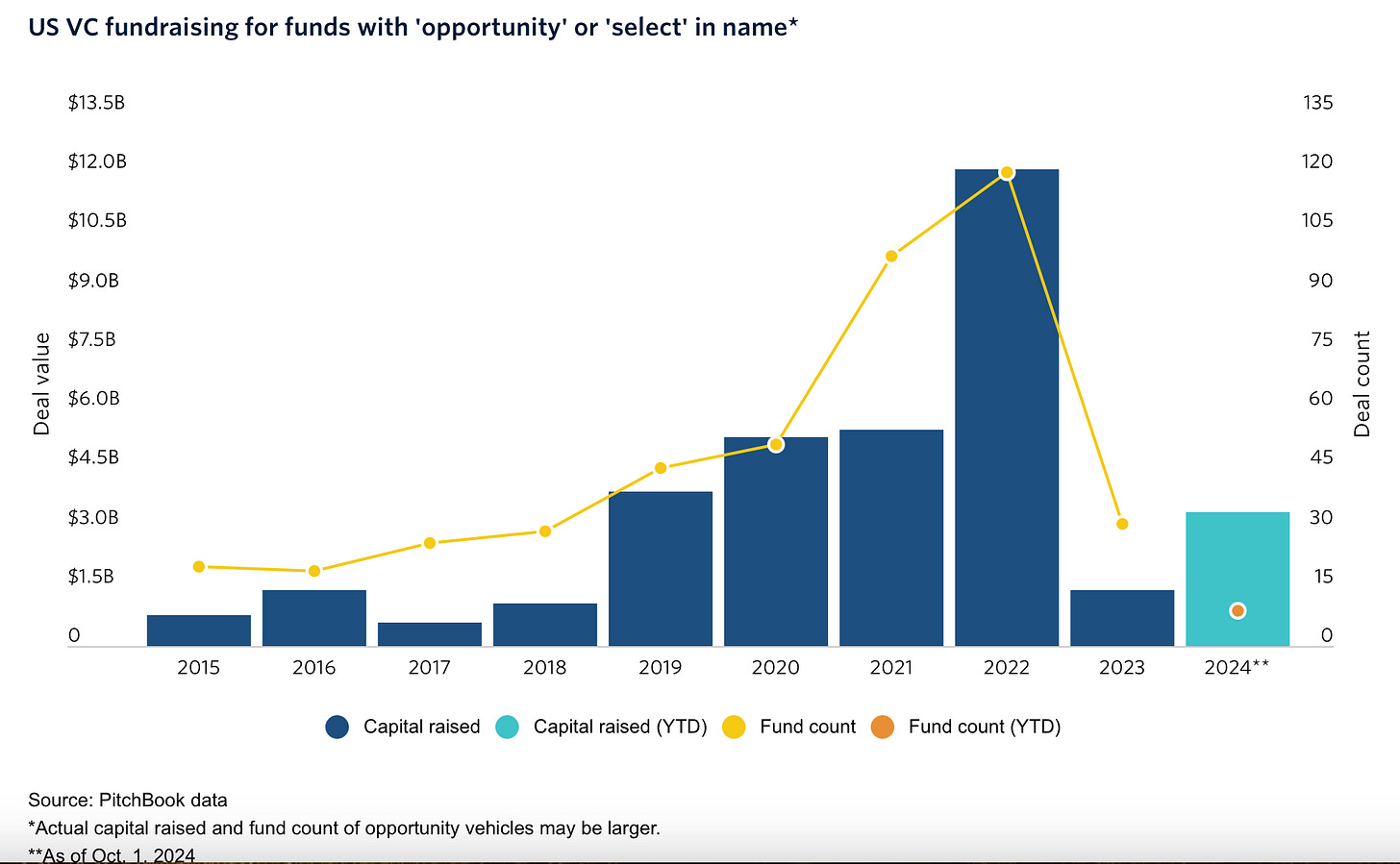

VC firms have raised at least $3.4 billion for opportunity-style funds this year, more than double last year’s total. Still, it’s a far cry from 2021, when at least 120 opportunity funds hit the market with a cumulative $12.1 billion.

Lightspeed, whose opportunity funds are among the industry’s largest, is angling to raise approximately $7 billion across three new vehicles, The Information reported. Up to 40% of that would be earmarked for opportunity-style investments.

But Lightspeed’s preliminary fundraising has reportedly emphasized secondary equity stakes and LP fund positions. The firm could also take controlling stakes and execute turnarounds of floundering firms.

That would depart from the typical opportunity fund playbook of throwing more cash at growing portfolio companies. The shift speaks to how VCs are adapting their strategies to a different market.

Too much money

CRV said there are too many hot startups, too flush with capital, to justify follow-on investments from a valuation perspective.

“Many of the 600 companies we have invested in have grown into market leaders, attracting huge attention and many dollars for their balance sheets,” CRV representatives said in a statement. “As a result, many of our best companies simply don’t need more capital. In addition, there is so much capital out there that as soon as a company shows signs of breaking out prices get driven up and return potential goes down.”

A spokesperson for CRV declined additional comment.

CRV’s current portfolio companies include Cribl, the data analytics platform that raised a $319 million Series E at a $3.5 billion valuation in August. It also led the Series A for no-code app platform Airtable, which was valued at $11.7 billion in 2021.

CRV’s assertion that the best startups have plenty of sources for cash may hold true broadly. But one sector, generative AI, seems ripe for opportunity fund-style investment: large language models require significant investment, and LPs are hungry for exposure.

With an eye on AI, tech-focused Kleiner Perkins raised $1.2 billion for its latest opportunity-style vehicle in June.

“Industries that have been slower to adopt software, and that require human labor for low-level work, like healthcare, legal, finance will see rapid transformation,” the firm said in a statement at the time. “New experiences and the demands of computation will open up opportunities in hardware and physical infrastructure. Imagination is now the constraining factor of the future of technology.”

Paul Hsu, founder and CEO of Decasonic of Chicago, which backs tech and crypto startups, said CRV’s call fell in line with market conditions.

“CRV is a multi-decade firm with multi-decade relationships with LPs, who recognize late-stage strategy requires adjusting, given market conditions,” Hsu said. “LPs applauded when they did this because CRV pursues investments not with greed or to milk fees but because they’re LP-focused.”

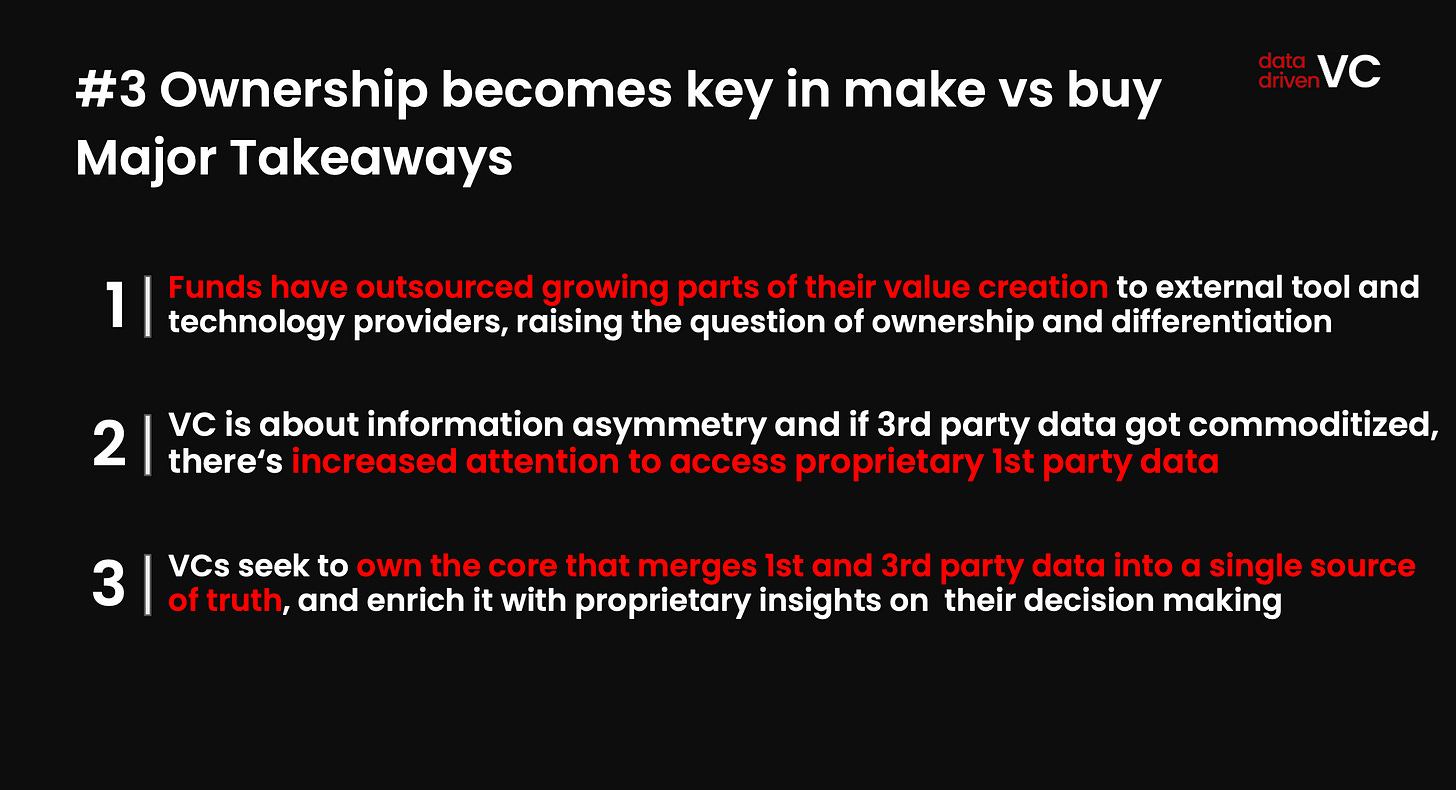

Why Should VCs Become More Data-Driven?

I just gave a virtual keynote about my “Data-Driven VC Outlook for 2025” at Vestberry’s Venture Intelligence Day. For everyone who wasn’t able to attend or wants to have another look at the content, I decided to publish select slides below and make the full presentation available for download here. Enjoy!

Status Quo: Recap Data-Driven VC Landscape 2024

We published the Data-Driven VC Landscape 2024 early May and you can access the full report for free here. Key insights from the 190 DDVC firms in our list below.

The previous slide serves as the foundation for my 2025 predictions: While the total number of DDVC firms has grown from 151 to 190 (=26% YoY), the total number of engineers across these firms has only grown from 767 to 865 (=13% YoY) May 2023 vs May 2024. Said differently, we have many new firms who are just getting started.

Outlook 2025

… and I expect this trend to extend into 2025: It’s still day one and majority of VC firms are yet to hire their first engineer and start their digitization journey. If I’d go by the number of firms who reached out to me asking basic questions on how to best start out and make the first hire, I’d expect the number of DDVC firms to at least grow again at the same rate, easily surpassing 250 firms globally in 2025.

Hereof, I expect three major trends:

..More

Video of the Week

Interview of the Week

Startup of the Week

Is $7.2B a lot of money for Squarespace?

OCT 17, 2024

The dance between Permira, a giant bucket of money, and Squarespace, a company that sells website-building tools, has concluded. Squarespace is now owned by Permira for an “aggregated transaction value of approximately $7.2 billion,” according to the company.

TechCrunch has a great ticktock on the deal, explaining how Squarespace managed to juice its exit price from $44 per share to $46.50. That’s not pocket change when we’re discussing a deal valued in the billions.

To understand the deal we need a few more facts. First, what was the premium that Permira paid, and how do the companies calculate the figure?

The revised offer price represents an increase of 5.7% over the previously agreed offer price of $44.00 per share, a premium of 36.4% over Squarespace's 90-day volume weighted average trading price of $34.09 and a premium of 21.8% over Squarespace's 52-week high share price of $38.19 as of May 10, 2024. The transaction also represents over 20x enterprise value / 2025 unlevered free cash flow, representing a significant premium to peers.

Selling for more than a one-third premium over your 90-day average price and more than a one-fifth premium to your 52-week high is not bad.

What did Squarespace have that Permira was willing to pay so much for? The following, per Squarespace’s Q2 2024 earnings:

Above-median revenue growth: 20%, to $296.8 million from $247.5 million in the year-ago quarter.

No-bullshit profits: Squarespace turned in $6.1 million worth of net income in the quarter, up from $3.7 million in the year-ago period.

Lots of cash and cash generation: Squarespace reported cash and equivalents of $270.4 million, and “unlevered free cash flow” of $65.4 million, up 19% compared to its Q2 2023 result.

Strong SaaS-o-Nomics: The number of “total unique subscriptions” at Squarespace grew 21% year-over-year to 5.2 million.

Looking at all that, I, too, would love to own Squarespace. There’s so much you could do with it! Not only could you up product spend with spare cashflow, you could afford to do that and boost S&M outlays and add a few more points to its growth rate.

Or you could trade some growth (S&M spend, Squarspace’s largest operating cost category), and use the resulting expanded cash flow to buy back shares. They were, recall, trading for a lot less than someone was willing to pay for them.

All told I am skeptical of Squarespace selling itself. Things were going well!

So, did Permira have to pay up more than we would think fair, putting aside the Δ between what the capital vehicle and the public were willing to value the company?

Notably, Squarespace grew faster (20%) in Q2 2024 than it did in the first quarter, expanding from 19% year-over-year topline expansion to 20%. Acceleration, in this economy?

Every point of growth matters. Per Bessemer’s cloud index, the median revenue growth rate amongst public cloud companies have fallen to 15%, with the top quartile clocking in at 22%. Squarespace’s 22% free cash flow margin in the second quarter was also above-median (18%), though somewhat distant from upper-quartile status (27%).

Squarespace therefore deserves a price that is between the median revenue multiple we’re seeing amongst public cloud companies, and what the upper-quartile earns. Those are 6.46x and 10.2x. Let’s arithmetic!

Squarespace Q2 2024 annualized run rate: $1.19 billion.

Squarespace valuation at run-rate*median cloud revenue multiple: $7.69 billion.

Squarespace valuation at run-rate*top quartile cloud revenue multiple: $12.1 billion.

Those are larger numbers than Permira paid. So Squarespace sold cheap? There’s nuance. Squarespace sold off a $400 million business to AmEx this summer. And, we aren’t taking into account the company’s cash position viz its enterprise valuation.

But even with those niggles, Squarespace’s exit feels light. Certainly, it’s a fat premium over what the market said Squarespace was worth, but we’re measuring from the period of time when interest rates were at local maximums. Money is getting cheaper. Valuation multiples could expand a little.

..More

Post of the Week

News Of the Week

Microsoft and OpenAI’s Close Partnership Shows Signs of Fraying

The “best bromance in tech” has had a reality check as OpenAI has tried to change its deal with Microsoft and the software maker has tried to hedge its bet on the start-up.

By Cade Metz, Mike Isaac and Erin Griffith

Reporting from San Francisco

Oct. 17, 2024

Last fall, Sam Altman, OpenAI’s chief executive, asked his counterpart at Microsoft, Satya Nadella, if the tech giant would invest billions of dollars in the start-up.

Microsoft had already pumped $13 billion into OpenAI, and Mr. Nadella was initially willing to keep the cash spigot flowing. But after OpenAI’s board of directors briefly ousted Mr. Altman last November, Mr. Nadella and Microsoft reconsidered, according to four people familiar with the talks who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Over the next few months, Microsoft wouldn’t budge as OpenAI, which expects to lose $5 billion this year, continued to ask for more money and more computing power to build and run its A.I. systems.

Mr. Altman once called OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft “the best bromance in tech,” but ties between the companies have started to fray. Financial pressure on OpenAI, concern about its stability and disagreements between employees of the two companies have strained their five-year partnership, according to interviews with 19 people familiar with the relationship between the companies.

That tension demonstrates a key challenge for A.I. start-ups: They are dependent on the world’s tech giants for money and computing power because those big companies control the massive cloud computing systems the small outfits need to develop A.I.

No pairing displays this dynamic better than Microsoft and OpenAI, the maker of the ChatGPT chatbot. When OpenAI got its giant investment from Microsoft, it agreed to an exclusive deal to buy computing power from Microsoft and work closely with the tech giant on new A.I.

..Lots More

The War of the AI Roses

Microsoft and OpenAI increasingly make strange bedfellows...

In the 1989 film The War of the Roses,1 a seemingly picture-perfect marriage between Oliver Rose (Michael Douglas) and Barbara Rose (Kathleen Turner) deteriorates over time to the point where disagreements turn into sabotage as neither side will agree to move out of their shared mansion. They keep living together, but it's increasingly an absurd situation. That's where my mind went when reading the latest about the drama between Microsoft and OpenAI.

Publicly, both sides continue to put out statements that everything is fine, so as to try to deflect such reporting. But they read as half-hearted attempts at best. There is just too much smoke coming out of the kitchen for there to be no source of heat.

I started writing about this friction back in March, around the Inflection acquisitionhackquisition, which even back then clearly felt like a hedge of sorts – albeit an expensive one – against what had happened with the brief ouster of Sam Altman at OpenAI. By May, a tension felt palpable even to us outsiders. And a series of events in the intervening months has seemingly made things even more awkward. From boardroom drama to personnel challenges to sales rivalries to more Microsoft hedging – while that initial hedge started to produce fruits of its own...

And now consider today's stories. The New York Times has the headline 'Microsoft and OpenAI’s Close Partnership Shows Signs of Fraying'. The story, reported by Cade Metz, Mike Isaac, and Erin Griffith (with additional reporting by Karen Weise and Tripp Mickle) – so, five reporters working sources – at one point cites "19 people familiar with the relationship between the companies" in reporting how strained the five-year partnership has become. Nineteen.

Meanwhile, not to be left out of the reporting fun, The Wall Street Journal today has a story entitled 'The $14 Billion Question Dividing OpenAI and Microsoft'. That story, reported by Berber Jin and Corrie Driebusch (with additional reporting by Tom Dotan) – so, three reporters working sources – details how the complicated process to morphOpenAI from a non-profit to a for-profit company is further driving a wedge between themselves and Microsoft, and this is likely to get even messier once the situation is sorted.

Again, these are just the latest in a series of stories from many different publications over an extended period of time that have painted a picture not unlike the plot of The War of the Roses. We're perhaps not at the point of throwing vases at one another yet. But we're seemingly not far from that either as the two sides not only remain bedfellows, but have furthered their commitment to one another in this latest OpenAI funding round, which saw Microsoft invest yet again. I had been wondering just how much (and in what form) the investment would be, and if my skills of deduction are correct, it seems like roughly $750M in new commitments came from Microsoft recently – taking the previous $13B invested up to $13.75B, as the WSJ reports. It's still not clear if that's cash or cloud credits (or some split), but they're roughly the same thing here since most of that money flows back to Microsoft anyway to run OpenAI's models on Azure servers.

But actually, as the NYT report details, Microsoft initially didn't want to invest more money into OpenAI. Spooked by the ouster of Altman – an event which we're coming up upon the year anniversary of, even though it feels like five years ago – Microsoft started to think about hedging, reports... well, basically everyone at this point. Of course, once this round was coming together, Microsoft basically had to invest. They're already so wedded to the company that not only would it optically look bad, it would potentially harm their own large stake.

Hike in capital gains tax will spark tech exodus from UK, investor says

Harry Stebbings says tax rules make Britain ‘a bad place to do business’ as he warns of entrepreneurs leaving

Dan Milmo Global technology editor

Thu 17 Oct 2024 12.48 EDT

Tech entrepreneurs will leave the UK “en masse” if the chancellor announces a significant increase in capital gains tax at this month’s budget, according to a leading industry investor.

Harry Stebbings, a British podcaster turned investor who raised a $400m (£310m) fund this week, said the UK was “a bad place to do business” because of its tax environment.

The Guardian reported last week that the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, was considering raising capital gains tax (CGT) to between 33% and 39% in the budget on 30 October.

Stebbings said plans to scrap the non-dom tax regime had also sent a negative signal but an increase in CGT – which is levied on the sale of assets such as shares and second homes – would pose the most serious concern to entrepreneurs.

“The stance on capital gains tax is by far the biggest [issue],” he told the Guardian. “Why would you look to invest in the UK if you’re looking at a 35% CGT rate, or wherever it lands.”

The 28-year-old said tech entrepreneurs would leave the UK if a significant increase in the tax was unveiled by Reeves. “I know fewer entrepreneurs will be here. They will leave en masse,” Stebbings said.

By contrast, a group of millionaire business owners have urged Reeves to raise £14bn through an increase in CGT, arguing it would have no impact on investment in Britain.

The chancellor is considering raising CGT on the sale of shares but not second homes, the Times reported on Thursday.

Keir Starmer, indicated this week that the tax would not rise as high as 39%, describing that number as “getting to the area which is wide of the mark”. However, the prime minister did not elaborate further on the probable rate. For higher rate taxpayers CPT on residential property sales is 24% and for shares and other assets it is 20%.

On Thursday a group of millionaire entrepreneurs backed a CGT rise in a report by the centre-left IPPR thinktank in which they urged Reeves to raise £14bn by increasing the tax, suggesting such a move would not “scare away real investors” in Britain.

The London-based fund led by Stebbings, 20VC, has become one of the most powerful players in European tech investment after its latest fundraising, which included backing from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Josh Kushner, the founder of OpenAI investor Thrive Capital.

Stebbings’s popular podcast, The Twenty Minute VC, has interviewed entrepreneurs including OpenAI’s Sam Altman and LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman. Stebbings told the Financial Times this week: “We leverage media to be the best investor.”

He said London and the UK faced competition as a tech base, with impressive talent building up elsewhere in Europe including in Paris, Munich and Amsterdam.