A reminder for new readers. Each week, That Was The Week includes a collection of selected readings

on critical issues in tech, startups, and venture capital. I chose the articles based on their interest to me. The selections often include viewpoints I can't entirely agree with. I include them if they provoke me to think. The articles are snippets or varying sizes depending on the length of the original. Click on the headline, contents link, or the ‘More’ link at the bottom of each piece to go to the original. I express my point of view in the editorial and the weekly video below.

Hat Tip to this week’s creators: @BillDee3723, @reidhoffman, @coryweinberg, @EricNewcomer, @johnsfoley, @cduhigg, @PeterJ_Walker, Zhen Yang, @readmaxread, @miro, @ColinRugg, @cookie, @ttunguz, @jasonlk

Contents

Reversing Aging with Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of Altos Labs

Neal Baer on CRISPR

Miro’s Innovation Workspace

Democrats Fail on Elon Musk

Geoff Hinton and John Hopfield win Nobel Prize in Physics for their work in foundational AI

DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis and John Jumper scoop Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold

How stuck is the startup exit market? Pretty stuck, says Pitchbook

OpenAI pursues public benefit structure to fend off hostile takeovers

Fourteen AGs sue TikTok, claiming that it harms children’s mental health

Russia bans Discord chat program, to the chagrin of its military users

Editorial

OpenAI’s $6.5 billion venture round produced lots of reaction this week. Many attempted to understand its $150 billion valuation. Some tried to use numbers to do so, most interestingly Cory Weinberg from The Information, Eric Newcomer and MG Seigler on Spyglass.

The results were varied. Weinberg starts his essay with:

OpenAI’s newest investors have signed up for a bumpy and expensive ride. The company’s projections suggest it won’t turn a profit until 2029, when its revenue would hit $100 billion.

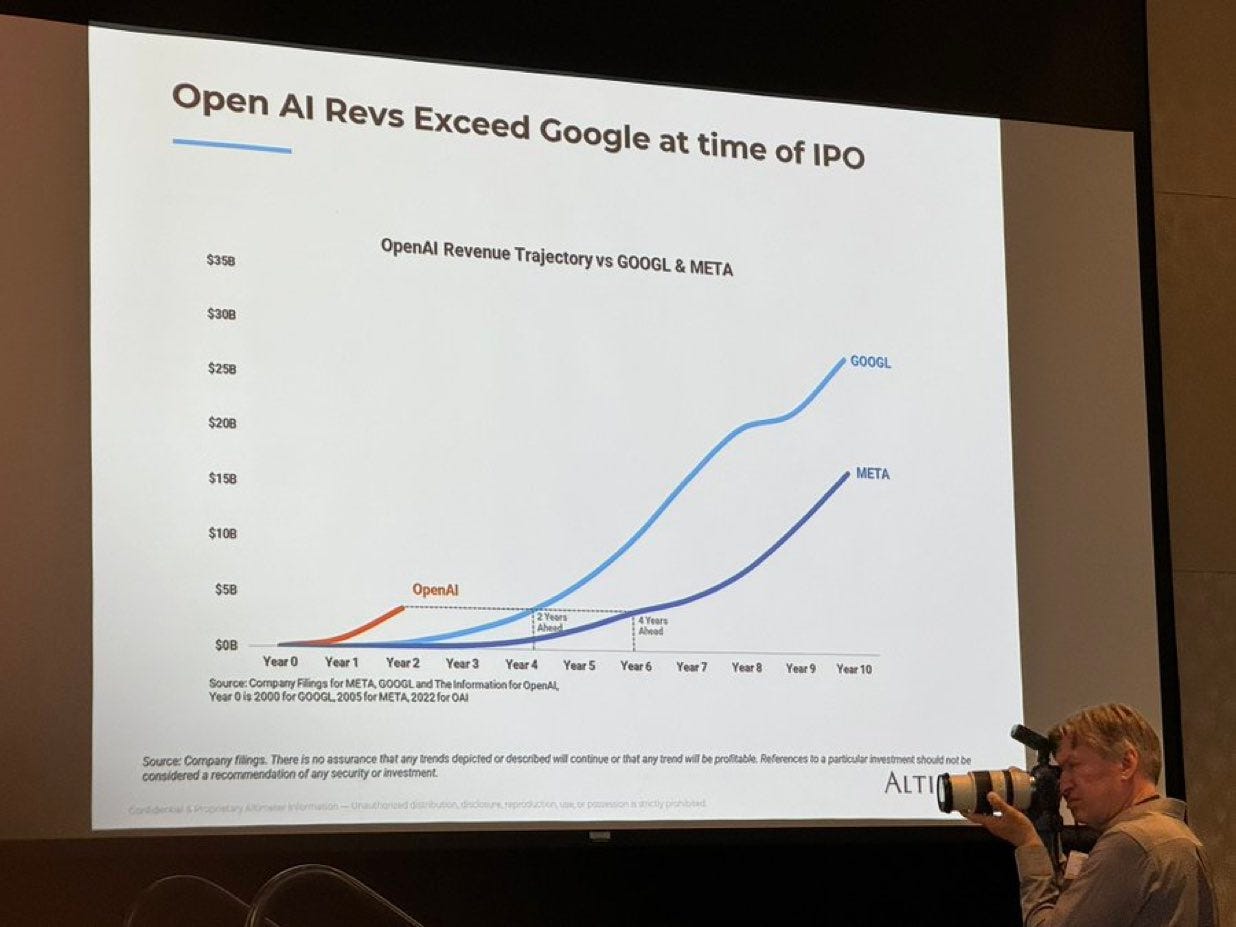

He includes the following chart.

MG speculates on how OpenAI will ever produce an outcome for its investors, musing about how public markets will be “willing to tolerate a massively money-losing company.”

What is missing from this is any analysis of the enterprise value OpenAI can expect from its revenues. Or any objective analysis of whether the projections will likely be missed, met, or exceeded.

Google has an enterprise value of $2 trillion and annual revenues of $330 billion. So the right question might be: Can OpenAI be as big or bigger than Google? And how fast?

Its revenue journey to $4 billion is far faster than Google’s. As Reid Hoffman speculates in “Superagency,” OpenAI may have a far more significant impact on humanity than Google search, enormous as that is. At $100bn in revenue, OpenAI is worth 30% of Google. But if Reid is right about the impact and the timing is faster than anybody envisages, OpenAI could eclipse Google’s revenue numbers.

An investor would construct a J Curve of costs and Outcomes over time. By the time OpenAI gets to $44 billion in revenue (2027 in these projections), I estimate it will have spent an accumulative $30 billion on costs. That would take five years (2023-2027). The following two years would add $141 billion to the cash flow.

This is a spectacularly good J Curve. And the rate of growth would far exceed Google’s.

What would have to occur for OpenAI to be this big? It's not that much beyond its projections. And those projections could be either too low or too high. My bet would be too low.

Bill Durodie has a wonderful research paper on “How the EU strangles innovation” focused on the “Precautionary Principle.” He notes:

In 1992, the notion of a precautionary principle was incorporated into the founding Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty), as Article 130r, Point 2 of Title XVI on the Environment.1 It came to take on a central role in the fledgling Union. Its reach and stature subsequently grew, primarily through various legal rulings, until it now shapes most policy areas across the EU.

OpenAI clearly has not been influenced by the “Precautionary Principle” and neither has Reid Hoffman. In his essay about “Superagency” he writes:

AI will enable our next great leap forward. In contrast to innovations like books or how-to videos on YouTube, AI isn't just a way to manufacture and distribute knowledge, as valuable as that is. Because an AI has the capacity to be agentic itself, setting goals and taking actions on its own to achieve them, you can leverage AI in two distinct ways. In some instances, you might want to work closely with an AI—such as when you're learning a new language or practicing mindfulness skills. In others, such as optimizing your home's energy consumption based on real-time energy prices and weather forecasts, you might prefer to let an AI handle that by itself.

He differentiates AI from prior innovations due to its ability to act as an agent itself. And he postulates:

Superagency is what happens when a critical mass of individuals, personally empowered by AI, begin to operate at levels that compound throughout society. In other words, it's not just that some people are becoming more informed and better-equipped thanks to AI. Everyone is, even those who rarely or never use AI directly.

None of this is baked into OpenAIs numbers. But it will appear in its actual numbers.

$6.5 billion at $150 billion valuation is cheap if you can get in (which you probably cannot).

Other exciting themes this week. What is real-time news becoming? Max Read describes how badly social media deals with news:

None of these people are particularly informative or helpful; they’re barely even entertaining. All these videos--which are generally what surfaces to the top when you search “Milton” on TikTok or Twitter--are new recombinations of the same kinds of awful reality-TV motifs that now dominate every social network: endurance challenges to unclear end; wealth porn and self-aggrandizement; and, most importantly, mental illness as a form of entertainment. It’s just that, instead of watching them because you’re bored, you watch them because they’re what comes up when you’re looking for information about an ongoing news event on social media.

That contrasts with Zhen Yang’s piece about how data science is impacting the New York Times.

But the hat tip of the week goes to the New Yorker for its story about how Silicon Valley is becoming good at politics. The article charts the career of Chris Lehane, who has helped many Valley companies achieve their policy goals. Lehane understands that big tech companies have going audiences in the tens or hundreds of millions:

“If Airbnb can engage fifteen thousand hosts in a city, that can have an impact on who wins a city-council race or the mayoralty,” Lehane told me. “In a congressional or Senate race, fifty thousand votes can make all the difference.” Of course, simply having a huge user base doesn’t guarantee that Airbnb can get everything it wants. Voters respond only to enticements that they find persuasive. But companies like Airbnb, Lehane understood, could make arguments faster, and more efficiently, than nearly any political party or other special-interest group, and this was a source of considerable power. “The platforms are really the only ones who can speak to everyone now,” Lehane said.”

And if you can deploy the power of those people in politics, then politicians tend to listen:

The only fixed truth about technology is that change is inevitable. Most of the tech industry “has run independent of politics for our entire careers,” Andreessen wrote when he announced that his political neutrality was over. Going forward, he would be working against candidates who defied tech. As Andreessen saw it, he didn’t have a choice: “As the old Soviet joke goes, ‘You may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you.’ ”

It is true that we live in a time when “politics is interested in you.” We humans like it when our lives improve. OpenAi, AirBnB, Google, Amazon, Apple, and others deliver on that. Social Media has more questionable upside. The “Precuationary Principle” in the EU would never give those benefits. Indeed it does the opposite, slowing or disabling them.

I know which side I am on.

Essays of the Week

How the EU Strangles Innovation

Bill Durodie

Superagency

Reid Hoffman

Co-Founder, LinkedIn & Inflection AI. Investor at Greylock.

October 9, 2024

At the center of many technological debates lies a fundamental question about human agency—our ability to make independent choices, act upon them, and exert influence over our lives. The rise of artificial intelligence is challenging the very concept of human agency, forcing us to ask whether we can continue to direct our own destinies or if, by relying on intelligent systems, we risk yielding control over the decisions that define our lives.

Consider the myriad of issues surrounding AI:

Job displacement: Will I have the economic means to support myself, and opportunities to engage in pursuits I find meaningful?

Data privacy: Will my data be used against me or for me? How do I maintain the integrity of my own identity and preserve an authentic sense of self?

Disinformation and misinformation: How do I know who and what to trust as I make decisions that impact my life?

Tech company dominance: Am I losing control to corporate entities? Are they subtly manipulating me with algorithms to serve corporate interests rather than my own?

Each of these concerns circles back to the same core issue: human agency. But as AI systems evolve, their capacity for self-directed learning, problem-solving, and executing complex series of tasks without constant human oversight also increases. In time, this means more and more systems, devices, and machines will encroach on areas traditionally governed by human agency—including in ways that humans may find objectionable.

And even in instances where we welcome such cognitive offloading, other issues arise: What if, through over-reliance on machine agency and capabilities, our own skills and agency atrophy over time? What if the systems that are supposedly working on our behalf—and delivering outcomes we approve of—end up shaping our behaviors and choices in ways that we haven't explicitly consented to?

To understand how we might adapt to and benefit from AI, look no further than the smartphone revolution.

The smartphone example

If smartphones didn't exist and were suddenly proposed today, imagine the headlines:

"Big Tech to Release Device That Tracks Your Every Move"

"New Gadget Aims to Capture All Your Personal Data"

"Constant Connectivity: The End of Privacy as We Know It?"

These concerns aren't unfounded. Smartphones do indeed collect vast amounts of personal data, disrupt our attention spans, and facilitate other problematic behaviors. They've changed how we interact with the world and each other, sometimes in ways we might not have chosen if given the option beforehand.

Yet, despite these valid concerns, smartphones have become ubiquitous. Why? Because people recognize that while smartphones may limit certain aspects of their agency, they dramatically enhance it in others. The ability to access information instantly, communicate with anyone around the globe, navigate unfamiliar territories, and carry a powerful computer in our pockets has expanded our capabilities in ways that were unimaginable just a few decades ago.

And the smartphone is just one of many examples. From cars, steam power, and the internet, all the way back to the wheel, spoken language, and the controlled use of fire, the story of humanity is that we are defined by our capacity and commitment to creating new ways of being in the world through our tool-making. And now we have a new super-tool: AI.

AI, the super-tool

Working in tandem, intelligence and energy drive human agency, and thus human progress. Intelligence gives us the capacity to weigh options, and to envision and plan for different potential scenarios. Energy enables us to then take action on whatever we aspire to achieve. The more intelligence and energy we can leverage on our behalf, the greater our capacity to make things happen, individually and collectively.

AI will enable our next great leap forward. In contrast to innovations like books or how-to videos on YouTube, AI isn't just a way to manufacture and distribute knowledge, as valuable as that is. Because an AI has the capacity to be agentic itself, setting goals and taking actions on its own to achieve them, you can leverage AI in two distinct ways. In some instances, you might want to work closely with an AI—such as when you're learning a new language or practicing mindfulness skills. In others, such as optimizing your home's energy consumption based on real-time energy prices and weather forecasts, you might prefer to let an AI handle that by itself.

Either way, the AI is increasing your agency, because it's helping you take actions designed to lead to outcomes you desire. And either way, something new and transformative is happening. For the first time ever, synthetic intelligence, not just knowledge, is becoming as flexibly deployable as synthetic energy has been since the rise of steam power in the 1700s. Intelligence itself is now a tool—a scalable, highly configurable, self-compounding engine for progress.

AI will undoubtedly change aspects of our lives in ways that may initially seem uncomfortable or even threatening. While it's natural to focus on potential losses of agency, AI offers heroic gains in human capability—a concept I’ve begun referring to as "superagency."

A world of superagency

Superagency is what happens when a critical mass of individuals, personally empowered by AI, begin to operate at levels that compound throughout society. In other words, it's not just that some people are becoming more informed and better-equipped thanks to AI. Everyone is, even those who rarely or never use AI directly.

Because many of the colleagues, professionals, other people, and systems you interact with and rely on will be augmenting their capabilities with these new systems and agents too. So your auto mechanic will know exactly what that weird thump coming from your trunk means when you accelerate from a traffic light on a hot day. The physical therapist overseeing your recovery from knee replacement surgery will create a personalized rehabilitation program that adapts in real-time based on your progress, pain levels, and biomechanical data from wearable sensors. Public transit systems will use AI to optimize bus routes and schedules in real-time. Even ATMs, parking meters, and vending machines will become multilingual geniuses who understand your needs instantly and adjust to your preferences.

That's the world of superagency.

OpenAI Projections Imply Losses Tripling to $14 Billion in 2026

Oct 9, 2024, 2:17pm PDT

OpenAI’s newest investors have signed up for a bumpy and expensive ride. The company’s projections suggest it won’t turn a profit until 2029, when its revenue would hit $100 billion.

Before it gets to that point, losses could rise as high as $14 billion in 2026, nearly triple this year’s expected loss, according to an analysis of data contained in OpenAI financial documents viewed by The Information. This estimate doesn’t include stock compensation, which is one of OpenAI’s biggest expenses, although not one it pays in cash.

The Takeaway

• OpenAI burned $340 million in first half of 2024

• Company’s cash burn has been lower than previously thought

• OpenAI projects total losses from 2023 to 2028 to be $44 billion

OpenAI is emphasizing to investors a metric of profitability that excludes some major expenses, such as the billions it is spending annually on training its large language models, the documents show. By that metric, OpenAI projects it will turn profitable in 2026. The company last week completed a $6.6 billion funding round valuing it at $157 billion.

The documents, which include financial statements and forecasts, contain a number of revelations about OpenAI that may change perceptions of the company’s financial prospects:

OpenAI appears to be burning far less cash than previously thought. The company burned through about $340 million in the first half of this year, leaving it with $1 billion in cash on the balance sheet before the fundraising effort. But the cash burn could accelerate sharply in the next couple of years, the documents suggest.

At the same time, its net losses are steep due to the impact of major expenses, such as stock compensation and computing costs, that don't flow through its cash statement. OpenAI calculated its net losses to be $3 billion for the first half of the year.

OpenAI expects to spend more than $200 billion through the end of the decade, excluding stock compensation costs. Between 60% to 80% of its spending each year would go toward either training or running the models.

An analysis of the documents suggests that OpenAI projects its total losses between 2023 and 2028, excluding stock compensation, will be $44 billion. The same analysis suggests the company anticipates it will make $14 billion in profit on that basis in 2029.

In the first half of this year, the company reported stock compensation of $1.5 billion, likely equivalent to its revenue in the period.

The documents imply that Microsoft gets a cut of 20% of OpenAI’s revenues—which is higher than previously thought.

OpenAI is projecting that computing costs for model training could rise sharply in the next couple of years, to as high as $9.5 billion a year in 2026. That’s in addition to the amortized upfront costs of training for large language model research, which its financial documents report as research compute costs spread out over a number of years. That figure is also rising sharply, to more than $5 billion in 2026 from a projected $1 billion this year.

Some of OpenAI’s computing costs aren’t paid in cash. Microsoft advanced OpenAI computing credits as part of its $10 billion investment last year. And in the first half of this year, OpenAI recorded about $500 million of data center lease expenses covered by Microsoft, according to the documents and a person familiar with the matter.

It's unclear how many computing credits OpenAI has left. It's likely, however, that OpenAI will have to spend more of its own cash if it increases compute spending as much as projected in the documents. OpenAI also has been discussing borrowing money to try to set up data centers more quickly than Microsoft can, The Information reported this week.

Still, OpenAI could scale back the compute spending—for instance, if upcoming models have more staying power than prior ones because rivals aren’t able to catch up quickly, or if the models are less costly to train because of future breakthroughs. That would reduce the demands on its cash resources.

Investors may shrug off the spending if OpenAI’s hit product, ChatGPT, continues to grow as expected and the company is able to generate revenue from new products. By 2029, when OpenAI’s for-profit business is a decade old, the company expects to be generating as much revenue as Nvidia and Tesla each generated in the past 12 months.

That optimism helped the company raise $6.6 billion last week from new investors including SoftBank, Fidelity and MGX, and existing investors Thrive Capital, Khosla Ventures and Tiger Global Management.

The New York Times earlier reported some details of OpenAI's finances, including its revenue projections.

ChatGPT-Heavy Sales

OpenAI believes ChatGPT will continue to generate the majority of its revenue for years to come, far outpacing its sales of AI models to developers through an application programming interface. And it expects new products to surpass API sales before the end of 2025, hitting nearly $2 billion that year.

It isn’t clear what those new products might be, but the company is currently pursuing products involving agents that can use a person’s computer to handle complex and monotonous tasks, as well as a research assistant, people with knowledge of the company said. And it has discussed selling higher-priced subscriptions to its most advanced technology. Other products that haven’t fully hit the market include its Sora video generator, a more-direct competitor to Google Search, and software for developers of robots.

OpenAI is projecting a significant slowdown in the growth of API sales. It’s not clear why, although that’s an area where it faces surging competitors such as Anthropic, Microsoft and Google.

The projections likely rely on the presumption that the company will maintain its lead in developing AI even as it faces a growing list of competitors and more personnel defections.

Low Gross Margins That Could Fatten

OpenAI expects its gross margin—a profit metric that reflects the direct costs of its business as a percentage of revenue—to hit about 41% this year. That’s far below the 65% to 70% typical for cloud software startups. The higher costs are largely due to the computing power it takes to run existing models, called inference computing, which is expected to hit $1.8 billion this year out of $3.7 billion in revenue.

Right now, OpenAI spends slightly more on the direct costs of its business than Uber, another loss-making megastartup, did in 2016, three years before it went public.

OpenAI says the business model will improve, with a gross margin of 49% next year and 67% in 2028, as its revenues are growing faster than its compute costs.

One of OpenAI’s backers, Altimeter Capital, published a slide from the startup that seemed to underpin the reasoning behind the improvement: declining costs of inference. Altimeter cited OpenAI data showing the price it charges developers to use GPT-4 had dropped 89% between March 2023 and August 2024. “Business models that don’t make sense now will in the future,” posted Jamin Ball, a partner at Altimeter, on X in September.

..More

The Bear Case for OpenAI at $157 Billion

Analyzing OpenAI's $157 billion valuation

ERIC NEWCOMER, OCT 09, 2024

After more than a decade covering startup unicorns, the “oh my god investors are crazy; how could it be worth that?” story is a bit tired for me.

I covered the ins and outs of Uber for many years and was one of the main reporters writing SCOOP Uber lost billions of dollars last year. Is this sustainable?

We all watched WeWork, GoPuff, Bird, and others raise shocking amounts of money with high burn rates and prove the skeptics right. But others, like Uber, figured out how to turn their big business into a profitable one.

OpenAI’s latest fundraising round poses so many big questions that I couldn’t help but dig into the business.

Is OpenAI a good investment at a jaw-dropping $157 billion valuation? Is it an even bigger and better Uber? Or is it more like a WeWork? I’ve been talking to Silicon Valley investors and poring through the reporting. I’ll make my case for why I think new investors are making a mistake investing in this round.

Less than a year ago, I too was bullish on OpenAI. When we held a draft of unicorn AI startups at our Cerebral Valley AI Summit, I took a $75 billion handicap for the right to pick OpenAI first. There’s a lot of value in being the leader.

Since then OpenAI’s valuation has soared from $86 billion to $157 billion after the latest $6.6 billion funding round.

The Abridged Bull Case

Let’s start out with the bull case. I saw OpenAI investor Brad Gerstner deliver one version of it last week at Madrona’s IA Summit. Gerstner’s firm, Altimeter, was one of a number of investors, including Thrive, SoftBank, Tiger Global, Fidelity, Khosla Ventures, and MGX, to invest in this latest funding round.

Gerstner’s pitch goes like this: OpenAI is growing its revenue faster than Google and Facebook did in their early years. ChatGPT is the second-ranked iPhone app right now and is expected to bring in $2.7 billion in revenue this year, out of $3.7 billion in total company revenue, according to the New York Times.

OpenAI is valuable because it is able to turn its foundation model technology into a widely popular consumer and enterprise application. Technology alone wouldn’t justify the valuation. There were other search companies but Google agglomerated all the value by taking a big lead. This is a bet on ChatGPT and OpenAI’s ability to build real products.

OpenAI has 250 million weekly active users without much marketing spending, which is double an estimate of Google’s actives at the time of its IPO, Gerstner said.

OpenAI has forecasted $11.6 billion in revenue next year, meaning that it’s $157 billion valuation is a 13.5x multiple on forward revenue. That’s not exactly crazy. Investors set Facebook’s IPO price at a 13x revenue multiple to the next year’s $7.8 billion in revenue.

OpenAI has the most popular AI app and the best foundation model. It’s got the generational leader in Sam Altman. It’s got a money cannon behind it and a deep partnership with Microsoft. What’s not to love?

Google break-up reads like antitrust fan-fiction

A world where the tech giant gets dismantled is more plausible than it was, but investors have reason to be unfazed

OCTOBER 8 2024

Imagine a world where Google parent Alphabet, at $2tn the world’s fourth-largest listed company, is torn asunder. Its search engine goes one way, the Android operating system another. Web browser Chrome, advertising businesses, all set free in the name of fostering competition. It is a world Google’s detractors might welcome, but not the one investors see.

The US Department of Justice on Tuesday set out potential ways to defang Google’s illegal monopoly in general internet search. Its ideas, which a judge will consider over the coming year, range from the relatively mild, such as limiting payments to smartphone makers in return for exclusivity on their devices, to so-called structural remedies — in other words, a break-up. A day earlier, another judge decreed Google must open up the Play Store, its shopfront for apps, to competition.

The cases — plus a third one over advertising technology — are complex, but boil down to a common idea: Google has created innovative products users and advertisers love, but then used overly sharp-elbowed tactics to entrench them. Curtailing those specific practices, be they the near-$20bn it pays iPhone-maker Apple to displace other search engines on its devices, or the up to 30 per cent rents imposed on in-app payments, sounds sensible.

But if the question is how to reverse rather than stop monopolistic wickedness, it is not clear whether courts and prosecutors have the answer. Being bigger has made Google’s offering palpably better. Strip away Android or Chrome from search and there is every chance it will remain dominant. Customers may actively uphold the status quo. Europeans select a search engine when they set up a new phone; nine out of 10 still use Google.

Whatever courts may order, endless appeals are likely to push a final reckoning far beyond most investors’ horizon. Chief executive Sundar Pichai says Google’s trials will drag on for years; legal fees make little dent on a company set to make $80bn in free cash flow this year, by LSEG estimates. The longer it takes, the less it hurts. A dollar of profit forsaken today is worth a dollar; the same dollar lost five years hence, assuming Google has a 10 per cent cost of capital, is worth about 60 cents.

That makes it hard to see this as an existential threat. Investors so far do not: Alphabet’s shares have fared no worse than Microsoft’s since December’s unfavourable app store decision. That could reflect the fact that any real reckoning will take an age. Or that users will continue to favour Google even when they have other options. Either way, the implication is that an end to Google’s long-standing dominance remains the stuff of fantasy.

Silicon Valley, the New Lobbying Monster

From crypto to A.I., the tech sector is pouring millions into super pacs that intimidate politicians into supporting its agenda.

By Charles Duhigg October 7, 2024

One morning in February, Katie Porter was sitting in bed, futzing around on her computer, when she learned that she was the target of a vast techno-political conspiracy. For the past five years, Porter had served in the House of Representatives on behalf of Orange County, California. She’d become famous—at least, C-span and MSNBC famous—for her eviscerations of business tycoons, often aided by a whiteboard that she used to make camera-friendly presentations about corporate greed. Now she was in a highly competitive race to replace the California senator Dianne Feinstein, who had died a few months earlier. The primary was in three weeks.

A text from a campaign staffer popped up on Porter’s screen. The staffer had just learned that a group named Fairshake was buying airtime in order to mount a last-minute blitz to oppose her candidacy. Indeed, the group was planning to spend roughly ten million dollars.

Porter was bewildered. She had raised thirty million dollars to bankroll her entire campaign, and that had taken years. The idea that some unknown group would swoop in and spend a fortune attacking her, she told me, seemed ludicrous: “I was, like, ‘What the heck is Fairshake?’ ”

Porter did some frantic Googling and discovered that Fairshake was a super pac funded primarily by three tech firms involved in the cryptocurrency industry. In the House, Porter had been loosely affiliated with Senator Elizabeth Warren, an outspoken advocate of financial regulation, and with the progressive wing of the Democratic Party. But Porter hadn’t been particularly vocal about cryptocurrency; she hadn’t taken much of a position on the industry one way or the other. As she continued investigating Fairshake, she found that her neutrality didn’t matter. A Web site politically aligned with Fairshake had deemed her “very anti-crypto”—though the evidence offered for this verdict was factually incorrect. The site claimed that she had opposed a pro-crypto bill in a House committee vote: in fact, she wasn’t on the committee and hadn’t voted at all.

Soon afterward, Fairshake began airing attack ads on television. They didn’t mention cryptocurrencies or anything tech-related. Rather, they called Porter a “bully” and a “liar,” and falsely implied that she’d recently accepted campaign contributions from major pharmaceutical and oil companies. Nothing in the ads disclosed Fairshake’s affiliation with Silicon Valley, its support of cryptocurrency, or its larger political aims. The negative campaign had a palpable effect: Porter, who had initially polled well, lost decisively in the primary, coming in third, with just fifteen per cent of the vote. But, according to a person familiar with Fairshake, the super pac’s intent wasn’t simply to damage her. The group’s backers didn’t care all that much about Porter. Rather, the person familiar with Fairshake said, the goal of the attack campaign was to terrify other politicians—“to warn anyone running for office that, if you are anti-crypto, the industry will come after you.”

The super pac and two affiliates soon revealed in federal filings that they had collected more than a hundred and seventy million dollars, which they could spend on political races across the nation in 2024, with more donations likely to come. That was more than nearly any other super pac, including Preserve America, which supports Donald Trump, and WinSenate, which aims to help Democrats reclaim that chamber. Pro-crypto donors are responsible for almost half of all corporate donations to pacs in the 2024 election cycle, and the tech industry has become one of the largest corporate donors in the nation. The point of all that money, like of the attack on Porter, has been to draw attention to Silicon Valley’s financial might—and to prove that its leaders are capable of political savagery in order to protect their interests. “It’s a simple message,” the person familiar with Fairshake said. “If you are pro-crypto, we will help you, and if you are anti we will tear you apart.”

After Porter’s defeat, it became obvious that the super pac’s message had been received by politicians elsewhere. Candidates in New York, Arizona, Maryland, and Michigan began releasing crypto-friendly public statements and voting for pro-crypto bills. When Porter tried to explain to her three children why she had lost, part of the lesson focussed on the Realpolitik of wealth and elections. “When you have members who are afraid of ten million dollars being spent overnight against them, the will in Washington to do what’s right disappears pretty quickly,” she recalls saying. “This was naked political power designed to influence votes in Washington. And it worked.”

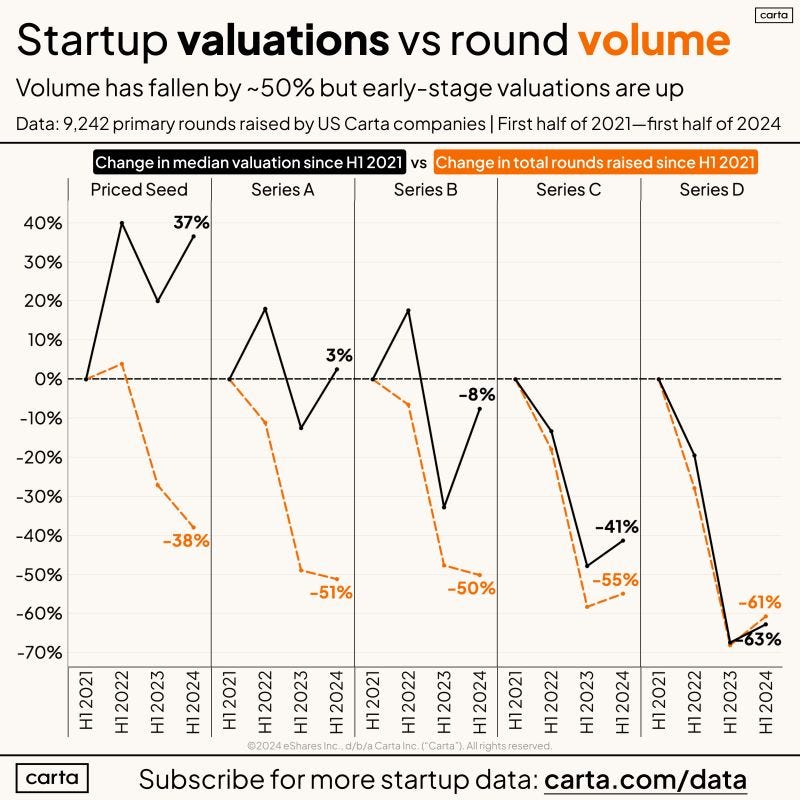

The startup world is weird right now.

Peter Walker • 1st • Head of Insights @ Carta | Data Storyteller

If you're looking to sum up .. [startup] .. weirdness, I think the chart below does a decent job.

Take that first column named Priced Seed. It shows that median valuations for seed-stage startups are 37% 𝗵𝗶𝗴𝗵𝗲𝗿 than they were in the first half of 2021. Yet there are 38% fewer rounds actually getting signed.

This gap persists in Series A and Series B, and then vanishes in the later stages where valuations and volume have declined in lockstep since the boom times ended.

What's up?

• Seed-stage valuations (as explored in some prior posts) have little to do with the underlying value of the business. They are prices dictated by belief in specific founders, first and foremost.

• Early-stage venture is actually getting crowded. Investors have moved earlier and earlier and the competition for the "best" rounds is fierce. Odd to think about given a 50% decline in total rounds, but true.

• We shouldn't expect round volume to approach the peaks of '21-'22 anytime soon, even with all this "dry powder" waiting to be deployed.

• No IPOs puts a lid on late-stage venture. Liquidity is a must-have for that part of the market to function properly.

Yes, some of this is down to AI frenzy at the early stages. But even if you remove AI companies, valuations at say Series A have not fallen in tandem with volume.

Weird times 🤷

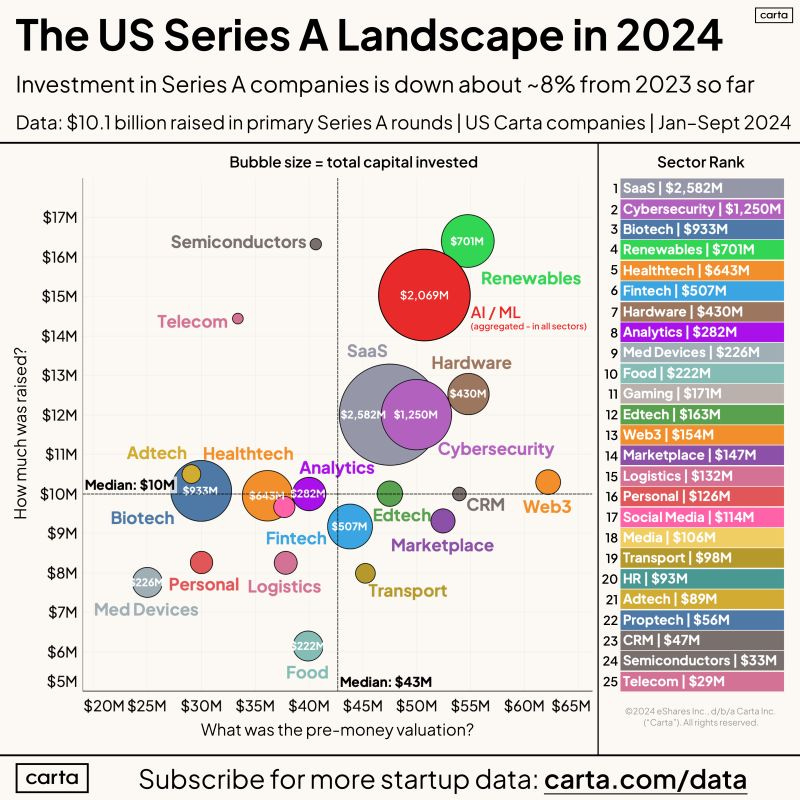

10 things to know about the Series A funding environment in 2024

Peter Walker • 1st • Head of Insights @ Carta | Data Storyteller

1. It's not all AI startups!

2. It is a lot of AI startups, though. ~25% of total invested capital is going to AI startups currently.

3. Total investment in Series A primary rounds is down about 8% over the same period last year. Hoping for a good Q4 to pop that back up.

4. Cybersecurity is the biggest riser as an industry, jumping from 8th to 2nd year over year.

5. Median cash raised = $10M, alongside a median $43M pre-money valuation (add those up and you get a very healthy $53M post-money valuation)

6. Only 3% of Series A rounds have a liquidation preference over 1x.

7. The mega-round is mostly absent from Series A - only 0.76% of rounds raised more than $100M.

8. The time between the seed round and the Series A has lengthened to nearly 2 years (median). Bridge rounds post first seed have become common (seed +, seed II, return of the seed, whatever today's name is)

9. Median percent of the company sold in a primary Series A round: 20.3%

10. This is perhaps the hardest jump to make right now in startup-world (to get from seed to A). Younger companies moving faster are starting to swamp older companies who raised their seed rounds in 2021 or early 2022.

How The New York Times incorporates editorial judgment in algorithms to curate its home page

The Times’ algorithmic recommendations team on responding to reader feedback, newsroom concerns, and technical hurdles.

By ZHEN YANG Oct. 9, 2024, 11:51 a.m.

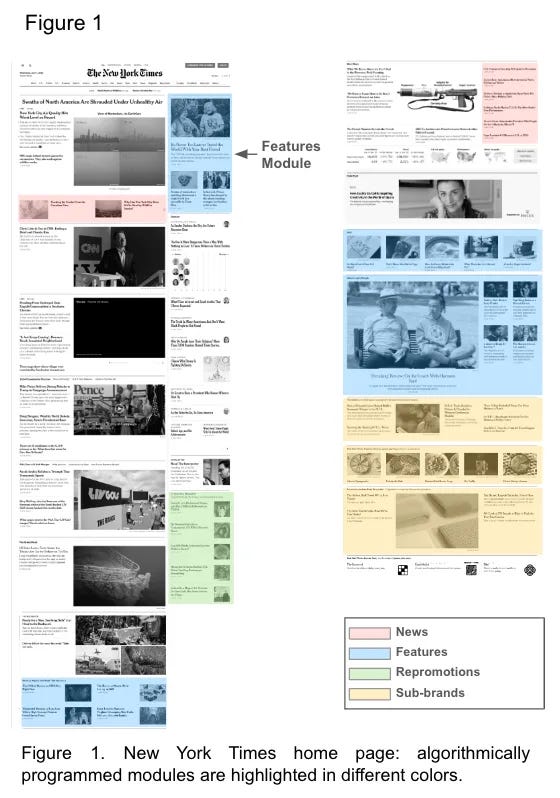

Whether on the web or the app, the home page of The New York Times is a crucial gateway, setting the stage for readers’ experiences and guiding them to the most important news of the day. The Times publishes over 250 stories daily, far more than the 50 to 60 stories that can be featured on the home page at a given time. Traditionally, editors have manually selected and programmed which stories appear, when and where, multiple times daily. This manual process presents challenges:

How can we provide readers a relevant, useful, and fresh experience each time they visit the home page?

How can we make our editorial curation process more efficient and scalable?

How do we maximize the reach of each story and expose more stories to our readers?

To address these challenges, the Times has been actively developing and testing editorially driven algorithms to assist in curating home page content. These algorithms are editorially driven in that a human editor’s judgment or input is incorporated into every aspect of the algorithm — including deciding where on the home page the stories are placed, informing the rankings, and potentially influencing and overriding algorithmic outputs when necessary. From the get-go, we’ve designed algorithmic programming to elevate human curation, not to replace it.

Which parts of the home page are algorithmically programmed?

The Times began using algorithms for content recommendations in 2011 but only recently started applying them to home page modules. For years, we only had one algorithmically-powered module, “Smarter Living,” on the home page, and later, “Popular in The Times.” Both were positioned relatively low on the page.

Three years ago, the formation of a cross-functional team — including newsroom editors, product managers, data scientists, data analysts, and engineers — brought the momentum needed to advance our responsible use of algorithms. Today, nearly half of the home page is programmed with assistance from algorithms that help promote news, features, and sub-brand content, such as The Athletic and Wirecutter. Some of these modules, such as the features module located at the top right of the home page on the web version, are in highly visible locations. During major news moments, editors can also deploy algorithmic modules to display additional coverage to complement a main module of stories near the top of the page. (The topmost news package of Figure 1 is an example of this in action.)

How is editorial judgment incorporated into algorithmic programming?

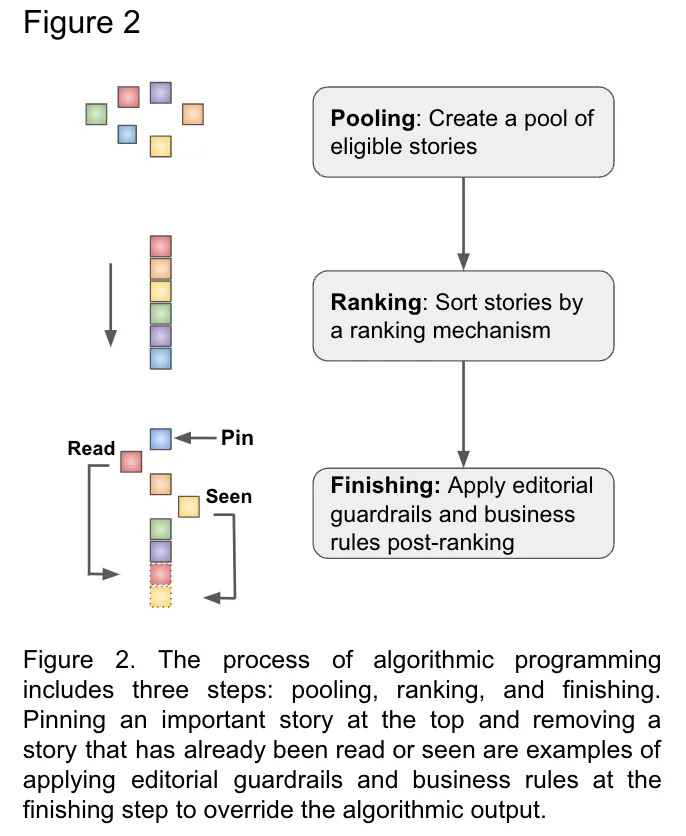

Algorithmic programming comprises three steps: (1) Pooling: Creating a pool of eligible stories for the specific module; (2) Ranking: Sorting stories by a ranking mechanism; and (3) Finishing: Applying editorial guardrails and business rules to ensure the final output of stories meets our standards. Editorial judgment is incorporated into all of these steps, in different ways.

To make an algorithmic recommendation, we first need a pool of articles eligible to appear in a given home page module. A pool can be either manually curated by editors or automatically generated via a query based on rules set by the newsroom.

A pool typically includes more stories than the number of slots available in the module, so we need a mechanism to rank them to determine which ones to show first and in what order. While there are various ways to rank stories, the algorithm we frequently use on the home page is a contextual bandit, a reinforcement learning method (see our previous blog post for more information). In its simplest form, a bandit recommends the same set of engaging articles to all users; the “contextual” version uses additional reader information (e.g., reading history or geographical location) to adjust the recommendations and make the experience more relevant for each reader. For an example of the geo-personalized bandit, see here.

The future of live news online sucks

Watching the hurricane through influencers' eyes

MAX READ, OCT 10, 2024

On Wednesday evening, where did you go to find up-to-the-minute news about Hurricane Milton? If you checked X.com at around 8 p.m., as the storm made landfall in Tampa and Sarasota, and clicked on the prominent “Hurricane Milton” link in the “Happening now” sidebar, you were taken to a landing page with a few videos from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and an exhortation to “check back later” because there was “nothing to see now.” Three hours later, at 11 p.m., nothing new had been added:

There was, of course, plenty to see on Wednesday night; it was just that it was basically impossible to find any of it on Twitter. The landing page was empty; the FYP feed worse than useless; the machine-curated hashtag pages a mix of days-old posts and influencers I’d never heard of sharing the same handful of images and videos. This was not a problem of “misinformation,” to be clear, so much as one of “no information”: Twitter seemed effectively incapable of serving me even relevant, up-to-the-minute fake stuff, let alone any actual news. Unless you’d already searched out and made a list of local journalists, meteorologists, and storm chasers, it was impossible to tell from Twitter alone where the storm was, how hard it was hitting, what its effects looked like, or how people were responding.

Instead--in place of the professional and citizen journalists, the eager experts, and the volunteer aggregators--what I found was clipped videos from a bunch of fucking freaks. There was Caroline Calloway, of course, who compared to some of the other creatures live-streaming their way through natural disasters out there comes across like a model of modesty and eloquence.

And you may have also already encountered “Lieutenant Dan,” the Florida man who promised to ride out the storm on his boat (he survived), though it’s not “Dan” who repels me so much as the assorted Twitter and TikTok and streamer personalities who have attempted coast in the slipstream of his viral success:

@terrenceconcannon @JoeSea on why he won’t leave the boat

Among the other characters I was introduced to as I tried and failed to seek any kind of reliable information about the storm was this rich lady in Tampa Bay who refused to evacuate “bc her husband (a builder) built the home commercial grade,” as well as her son, “Blade,” who has a star turn at the end of this video:

And Mike Smalls, Jr., a streamer on the Twitch competitor Kick (a kind of reactionary alternative to mainstream streaming platforms funded by an Australian gambling company), who attempted to ride out the storm on an air mattress because Adin Ross said he’d give anyone who did it $70,000.

This is, as Ryan Broderick put it, “the kind of thing that plays on TV in Robocop.”

None of these people are particularly informative or helpful; they’re barely even entertaining. All these videos--which are generally what surfaces to the top when you search “Milton” on TikTok or Twitter--are new recombinations of the same kinds of awful reality-TV motifs that now dominate every social network: endurance challenges to unclear end; wealth porn and self-aggrandizement; and, most importantly, mental illness as a form of entertainment. It’s just that, instead of watching them because you’re bored, you watch them because they’re what comes up when you’re looking for information about an ongoing news event on social media.

Video of the Week

(0:00) Introducing Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of Altos Labs (0:47) Breaking down the recent breakthroughs in aging reversal (22:48) Chamath and Friedberg join Juan Carlos on stage to discuss the magnitude of his research

Interview of the Week

Startup of the Week

Post of the Week

News Of the Week

Geoff Hinton and John Hopfield win Nobel Prize in Physics for their work in foundational AI

Paul Sawers 4:12 AM PDT · October 8, 2024

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has announced the Nobel Prize in Physics 2024. Geoff Hinton and John Hopfield are jointly sharing the prestigious award for their work on artificial neural networks starting back in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

More specifically, Hinton and Hopfield were given the award for “foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

The news comes as AI has emerged as one of the major driving forces behind what some have dubbed the fourth industrial revolution. Major innovators in the space are being recognized for their work. Earlier this year, Google Deepmind co-founder and CEO Demis Hassabis was awarded a knighthood in the U.K. for “services to artificial intelligence.”

Hinton is among the world’s most renowned researchers in the field of AI, laying the groundwork for much of the advances we’ve seen these past few years. He has often been referred to as the “godfather of deep learning.” After gaining a PhD in artificial intelligence in 1978, Hinton went on to co-create the backpropagation algorithm, a method that allows neural networks to learn from their mistakes, transforming how AI models are trained.

Hinton joined Google in 2013 after the search giant acquired his company DNNresearch. He quit Google last year citing his concerns over the role that AI was playing in the spread of misinformation. Today, Hinton is a professor at the University of Toronto.

..More

DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis and John Jumper scoop Nobel Prize in Chemistry for AlphaFold

It has been a big week for Nobel Prizes in the world of artificial intelligence. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences today announced the Nobel Prize in Chemistry winners for 2024, with DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis and Director John Jumper sharing one-half of the prize, with David Baker — who is head of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington — securing the other half.

The news comes a day after AI pioneers Geoff Hinton and John Hopfield won the Nobel Prize in Physics for their foundational work in machine learning and AI.

Hassabis and Jumper won the award, specifically, for “protein structure prediction,” while Baker’s was for “computational protein design.”

Protein fix

Proteins are the building blocks of life, which is why DeepMind’s work on AlphaFold has been so revolutionary. Though its potential had been touted for years, the Google subsidiary presented the second version of the AI model in 2020, going much of the way toward solving a problem that had stumped scientists for years by predicting the 3D structure of proteins using nothing more than their genetic sequence.

The shape of a protein dictates how it works, and figuring out its shape was historically a slow, labor-intensive process that would often require years of lab experiments. With AlphaFold, DeepMind was able to accelerate this to mere hours, covering most of the 200 million proteins in existence. The ramifications of this can’t be overstated, as this kind of data is vital to things like drug discovery, diagnosing diseases, and bioengineering.

“One of the discoveries being recognised this year concerns the construction of spectacular proteins,” Heiner Linke, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, said in a statement. “The other is about fulfilling a 50-year-old dream: predicting protein structures from their amino acid sequences. Both of these discoveries open up vast possibilities.”

Baker, for his part, secured his half of the prize for engineering entirely new kinds of proteins, designed computationally to perform specific functions within pharmaceuticals, vaccines, and so on.

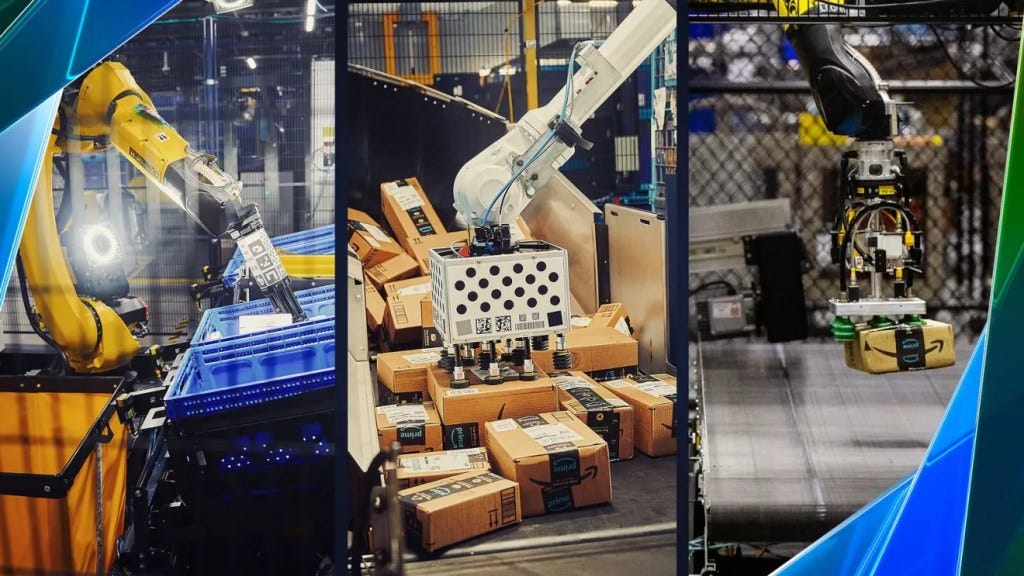

Amazon’s new warehouses will employ 10x as many robots

Brian Heater 8:05 AM PDT · October 9, 2024

At its Delivering the Future event Wednesday, Amazon announced plans for new robot-powered delivery warehouses. The first “next-generation fulfillment center” is located in Shreveport, Louisiana. The 3-million-square-foot warehouse spans five floors, constituting the rough equivalent of 55 football fields, per the company.

The site represents the culmination of Amazon’s work in robotics, which dates back more than a decade to its 2012 Kiva acquisition. The retail giant’s approach has largely revolved around incorporating robots into existing worklfows, so as to not disrupt regular operations. The new model looks to bring a more ground-up greenfield approach to robotics and AI.

Amazon has yet to announce specific figures in terms of robots deployed, only that it will bring 10x that of a standard fulfillment center. We do know, however, that the company already has nearly a million robotic systems deployed in centers across the U.S.

Along with the Kiva-style autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) and inventory robotic arms Robin, Cardinal, and Sparrow, the company is deploying Sequoia, which it refers to as “a state-of-the-art multilevel containerized inventory system that makes it faster and safer for employees to store and pick goods. In our next-generation facility, Sequoia can hold more than 30 million items.”

This version is 5x the size of the first Sequoia inventory system the company deployed in Houston around this time last year.

..More

How stuck is the startup exit market? Pretty stuck, says Pitchbook

Deal analysis outfit Pitchbook today released a new report that underscores how fewer exits are impacting the startup investing ecosystem.

Among its findings? Beyond what’s commonly known – that a lot of the fundings today are insider rounds and bridge financings aimed at keeping companies alive – cash back to the limited partners (LPs) who fund venture firms has slowed to the global financial crisis levels of 16 years ago. Meanwhile, with LPs snapping shut their checkbooks as their returns slow, the number of VCs and angel investors investing in a startup in the first quarter of this year fell to just 45.5% of those who were striking deals in 2021.

Pressure is building. VCs are sitting on unicorns that now account for $2.5 trillion in value, says Pitchbook — and nearly 40% of these have been in their VCs’ portfolio for at least nine years.

Overall, the backlog of companies yet to exit has ballooned to 57,674, a record high, with late-stage companies accounting for 32.4% of those outfits.

The Quiet Liquidity Crisis in SaaS

by Jason Lemkin | Blog Posts

So Thomasz Tunguz put together a great chart summarizing one of my top worries over the past 24+ months in SaaS. He summarized the M&A (acquisitions) of The Top 10 Software Acquirers.

And what you can see is there is really almost no liquidity for startups and scale-ups in SaaS and Cloud at the moment. And there hasn’t been for a while:

It was great times for SaaS liquidity in late 2020 through the end of 2021. Epic times.

In SaaStr Fund alone, we had billion+ cash exits in Salesloft ($2.4B), Pipedrive ($1.5B) and Greenhouse (almost $1B), among other deals. And 2021 was a record year for Saas IPOs. And VCs didn’t care if they got secondary shares (buying them from others) or new primary shares, so there were a ton of employee tender offers and buy-outs going on. Liquidity was everywhere. It really was.

But Since December 2021 it’s been rough for SaaS liquidity:

There have only been 3 SaaS IPOs since 2021: Klaviyo, Rubrik, and OneStream. Just 3. A record low.

The Top 10 Software acquirors’ M&A activity is down -90% or more from 2021. See above from Thomasz.

Now, to some extent, the issues here have been masked by several factors:

The VC engine continues, more or less, and has been re-energized by AI. Deals are fast and furious. Mostly this is actually anti-liquidity. Cash goes into illiquid shares. But the deal energy maintains a sense of momentum toward big liquidity events.

Top late-stage VC deals include tender offers and a material amount of secondary liquidity. Stripe recently did a VC deal that was all for employees and shareholders, a tender offer. OpenAI has done plenty of them. That’s liquidity. So this is ongoing, albeit really only at the top start-ups and scale-ups.

It’s “only” been 2.5 years or so. VCs and employees can more or less deal with ~2 years of illiquidity. We don’t fully expect it to be linear.

Public SaaS and Cloud companies, and AI leaders like NVidia, have still generated a lot of cash for shares. These are good liquidity times for employees at Samsara, Cloudflare, Klaviyo, etc. Just less so for start-ups and scale-ups.

What will the future bring for SaaS liquidity?

At the moment, it seems … mixed.

The Good:

There are some just epic IPOs, just waiting. Canva, Databricks, Wiz, ServiceTitan, and many more will generate billions and billions in liquidity. All could IPO today. They are just waiting.

Private Equity is still buying SaaS companies. Thomasz’ chart looks at the Top 10 public company acquirers by market cap. But mega PE firms Thoma Bravo, Vista, etc. are still buying big SaaS companies. Vista just bought Smartsheet for $8.4 Billion.

The Bad:

Public multiples remain low. This makes M&A (acquisitions) less attractive. Folks don’t want to overpay. Slack for $27 Billion by Salesforce at $1B ARR seems almost unfathomable today.

The bar to IPO sure seems high. Klaviyo, Rubrik, and OneStream (the only 3 SaaS IPOs since 2021) all were at $500m ARR growing 50% or so.

The Ugly:

Antitrust is a big mess. Not just in the U.S., but around the world. BigTech really will struggle to make any $1B+ acquisitions for real if antitrust somewhere will block it, like Figma and Adobe. It’s a big chilling effect. And VC and start-ups need $1B exits to make the math work. SaaS VCs need what I call a “Series of Looms” (which Atlassian bought for $1B) to make their model work. Loom did close, so it still happens. It’s just a lot harder for these big deals to happen.

One thing is clear: liquidity is harder to come by than any time for the past 7-8 years or so, as Thomasz’ chart points out.

It should get better. But maybe not that much better. The bar has gone up everywhere in SaaS and B2B.

OpenAI pursues public benefit structure to fend off hostile takeovers

ChatGPT maker considers largely untested company model to protect chief executive Sam Altman from outside interference

Cristina Criddle in San Francisco and Patrick Temple-West

OpenAI is pursuing a largely untested corporate structure to defend itself from hostile takeovers and protect chief executive Sam Altman from outsider interference.

The artificial intelligence start-up, which last week secured $6.6bn in new funding, is planning to restructure as a public benefit corporation, a new and rare type of company model also adopted by AI rivals including Anthropic and Elon Musk’s xAI. A key benefit of the PBC structure is its potential to thwart an unwanted acquisition or an activist’s demands, according to multiple people familiar with the company’s thinking. This means an existing investor such as Microsoft or another party could be frustrated if they mounted an effort to acquire OpenAI.

OpenAI’s PBC business would be obliged to balance the best interests of shareholders, a public benefit, and stakeholders, such as employees and society.

According to one person, this “multipronged approach to fiduciary obligations” for a company would give OpenAI a “safe harbour” to wave off activists who might claim the company is not making enough money.

It “gives you even more flexibility to say ‘thanks for calling and have a nice day’,” they added.

Alto Reveals New Fund In Partnership With SignalRank

By Amit Chowdhry • Oct 8, 2024

Alto Reveals New Fund In Partnership With SignalRank

Alto, an alternative asset platform that enables individuals to invest in alternative assets using retirement funds, announced a new investment opportunity with SignalRank, the first private markets index made up of preferred Series B shares in high-growth venture-backed companies.

Accredited investors can gain exposure to high-potential startups at early growth stages that align with their long-term investment objectives by investing at least $25,000 in the SignalRank Co-Investment Fund through Alto’s Marketplace.

Alternative investments with traditionally unique strategies that aren’t more widely publicly available have been largely limited to ultra-high-net-worth individuals and institutional investors due to their complexity and higher minimum investment requirements.

With the alternative asset market experiencing unprecedented growth, Alto aims to broaden access by offering eligible accredited investors the opportunity to invest in these deals, lowering the minimum investment requirements and working with funds usually limited to family offices and larger firms.

KEY QUOTES:

“The investment opportunity with SignalRank is an exciting one, as it provides eligible investors the ability to invest their retirement assets into high signal private companies. Alto is committed to offering investors more pathways to diversify and grow their portfolios, and SignalRank’s unique approach to investing in venture capital aligns with that mission.”

-Scott Harrigan, President of Alto and CEO of Alto Securities

“At SignalRank, we are passionate about providing investors with access to the highest potential early-stage companies in the world. We’re excited to partner with Alto as they are a forward-thinking company that offers diverse options for investing in venture capital, and we’re pleased to offer this new investment opportunity that can help broaden access for more investors to participate in this constrained space.”

-Keith Teare, CEO of SignalRank

Fourteen AGs sue TikTok, claiming that it harms children’s mental health

Fourteen U.S. attorneys general sued TikTok on Tuesday, alleging that the platform negatively impacts minors’ mental health and harvests data without their consent.

TikTok, a U.S. company owned by the Chinese conglomerate ByteDance, is embroiled in a number of lawsuits that could threaten its operations. In another recent lawsuit, the FTC and the Justice Department sued the platform for violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) by collecting data from users under the age of 13 without parents’ consent.

Meanwhile, TikTok is still slated to be banned in the U.S. if ByteDance doesn’t sell the company before January 19, 2025.

Russia bans Discord chat program, to the chagrin of its military users

The ban has also renewed a wider debate about how Russia’s bureaucratic machine keeps frustrating the military effort.

October 9, 2024 at 10:26 a.m. EDT

Russia has moved to ban Discord, a popular platform for real-time communication, drawing ire from the Russian military that has extensively used the app to coordinate units on the battlefield in Ukraine.

The ban, announced by the internet regulator Roskomnadzor on Tuesday, highlights a glaring technology lapse within the Russian military. More than 2½ years into the war, it has failed to implement a secure, dependable Russian-made communications system, instead relying on privately owned platforms such as Discord and Telegram.

The ban has also renewed a wider debate about how Russia’s bureaucratic machine keeps frustrating the military effort.

Pro-invasion military bloggers, many of whom have a direct line to units fighting in Ukraine, ridiculed the move, saying that a bureaucratic decision to block Discord caught Russian troops off guard and left them without proper communications.

Turkey blocks instant messaging platform Discord

By Reuters

October 9, 20246:24 AM PDT

ISTANBUL, Oct 9 (Reuters) - Turkey has blocked access to instant messaging platform Discord in line with a court decision after the platform refused to share information demanded by Ankara, Turkish authorities said on Wednesday.

"We are aware of reports of Discord being unreachable in Russia and Turkey. Our team is investigating these reports at this time," the San Francisco-based company said in a status update.

Turkey's Information Technologies and Communication Authority published the access ban decision on its website.

Justice minister Yilmaz Tunc said an Ankara court decided to block access to Discord from Turkey due to sufficient suspicion that crimes of "child sexual abuse and obscenity" had been committed by some using the platform.

The block comes after public outrage in Turkey caused by the murder of two women by a 19-year-old man in Istanbul this month. Content on social media showed Discord users subsequently praising the killing.

Transport and infrastructure minister Abdulkadir Uraloglu said the nature of the Discord platform made it difficult for authorities to monitor and intervene when illegal or criminal content is shared.

"Security personnel cannot go through the content. We can only intervene when users complain to us about content shared there," he told reporters in parliament.

"Since Discord refuses to share its own information, including IP addresses and content, with our security units, we were forced to block access."